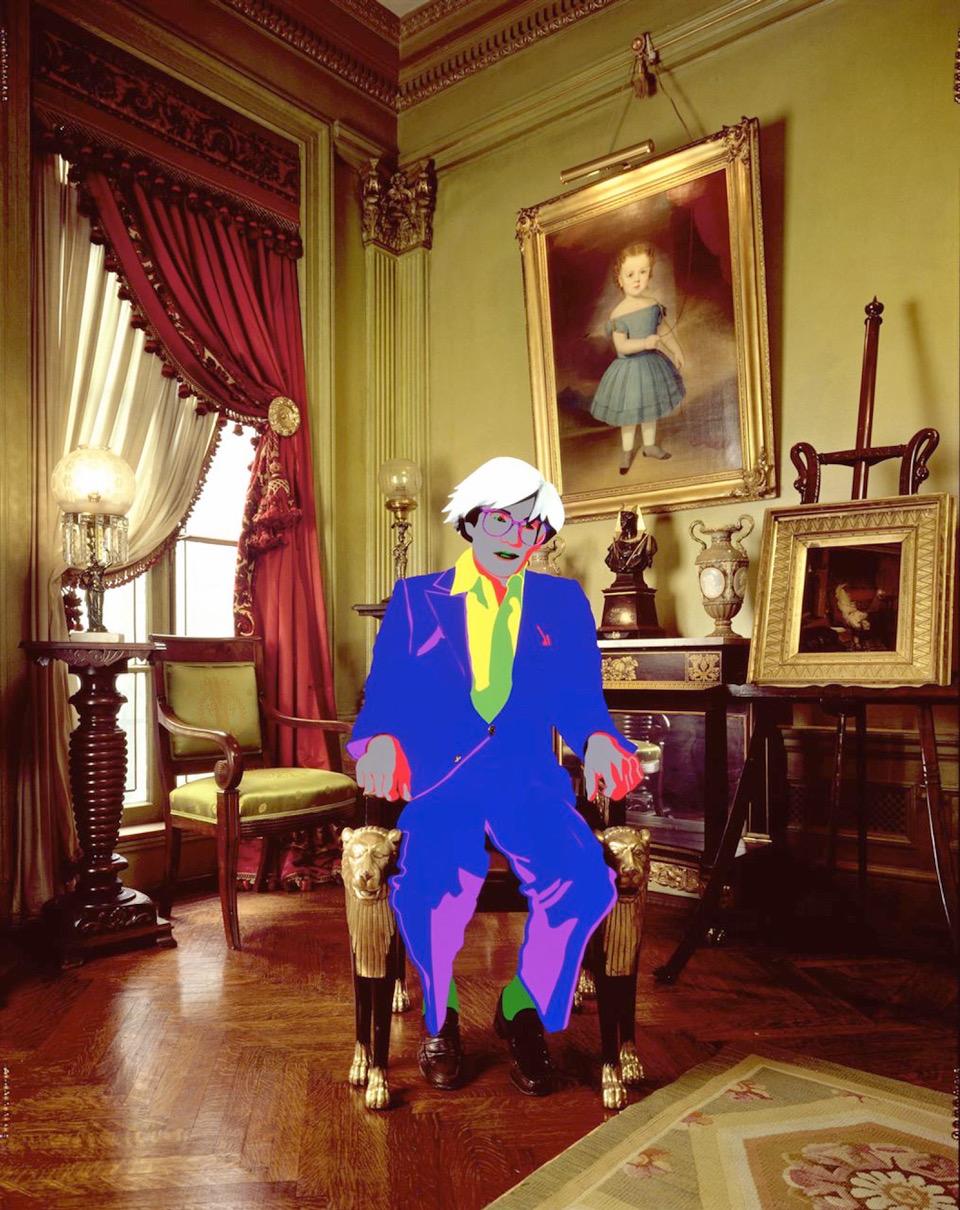

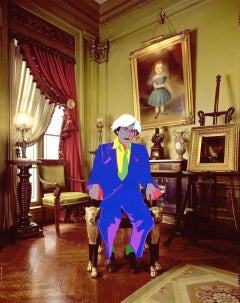

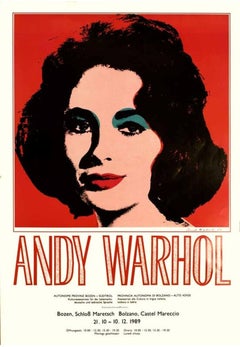

Fred Hughes in Andy Warhol’s Factory with Liz Taylor Painting

860 Broadway NYC 1987

Archival Inkjet on Paper

*Also available on Aluminum. Please inquire regarding sizing and prices*

Available sizes:

24 x 20 inches

Edition size: 10

Signed, titled, dated, and annotated in ink on the reverse, 1988, printed later; accompanied by a Certificate of Authenticity, signed and dated in ink.

Fred Hughes became Warhol’s business manager in 1967. He managed the Factory, Warhol’s famous studio, and, thereafter, took on the role of publisher for Interview magazine. Hughes was a figure of tremendous importance in the artistic life and legacy of Warhol. After the artist’s death, in 1987, he also became the executor of the artist’s estate.

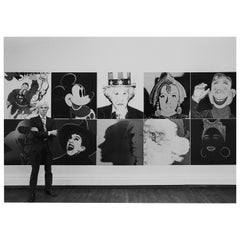

And most importantly, Hughes was the mastermind behind the 10-day, 1988 auction at Sotheby’s. Gamble’s photograph captures the éminence grise of Warhol’s empire in what became the sitter’s most favorite portrait. This image was taken at the Factory in 1987. Hughes is seen clutching a copy of Interview magazine engineered by Gamble in 1997 to feature a deliberately pop art inspired portrait of Warhol. In line with the other images in this series, this one too reveals lesser-known aspects of the artist's life and outstandingly successful career.

Though Fred Hughes certainly benefited from his association with Andy Warhol, the argument could certainly be made that Warhol, who died after gallbladder surgery in 1987, benefited even more from his association with Fred Hughes.

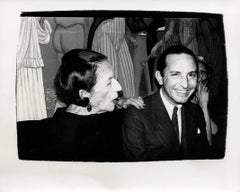

The de Menils clearly saw something in the young Mr. Hughes and helped him land a job at the Iolas Gallery in Paris, which represented Max Ernst and René Magritte. But he also continued to help out the family, and this often involved spending time at their Manhattan townhouse. In Bob Colacello’s Holy Terror , a memoir of his days with the Warhol Factory, Mr. Colacello recalls that it was during one of these stopovers that Fred Hughes encountered Andy Warhol, who was hanging out at the 60’s discotheque hotspot Arthur with doomed socialite Edie Sedgwick. Mr. Hughes, who had purchased his first Warhol while still in college, went up and shook the artist’s hand.

But, as Mr. Colacello also reports, Warhol and Mr. Hughes were formally introduced in 1967 at architect Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Conn. The setting was a benefit for Merce Cunningham’s dance company that was sponsored by the de Menils. Providing entertainment for the evening were the Velvet Underground. “Fred came with a de Menil daughter,” Mr. Colacello wrote. “Andy came with the band.” The two men were introduced by curator Henry Geldzahler, who says he never saw either of them again: “They waltzed off into the empyrean.”

Fred Hughes began working at the Factory, which had moved from East 47th Street to Union Square, by literally sweeping the floors. But he soon made himself indispensable to Warhol. Rather than immediately hit up the de Menils to buy one of Warhol’s portraits, Mr. Hughes first convinced them to commission the artist to immortalize their private curator, Germaine McConaghty. Soon enough, Dominique de Menil sat for her own portrait, as did Philip Johnson and other friends of the family.

Fred was a catalyst, somebody who is at the center of things, who enlivens things, makes things happen, somebody who is full of ideas, who sparks things. It was just what Andy needed in a way,” said the art historian and biographer John Richardson, who knew Mr. Hughes from their days together at the Factory. “Fred turned out to be this very cool, competent, albeit quite eccentric guy. All of us who were part of the Warhol world loved Fred. He kept things on a very even keel.”

Mr. Colacello agreed with Mr. Richardson’s assessment, and took it a step further. “In a few years, Fred engineered the rise of Andy Warhol from the demimonde to the beau monde and set him on the road to real riches,” he writes in Holy Terror . Although Leo Castelli was Warhol’s dealer, it was Fred Hughes who “launched the commissioned portraits gold mine, drove up the sales and prices of the sixties paintings, expanded the limited edition print biz, cultivated important news collectors and dealers, especially in Europe.” In 1971, Mr. Hughes also rescued Interview from financial ruin by lining up new backers.

At the time, Fred Hughes was only 27 years old.

Mr. Hughes’ influence on Warhol was not limited to business. “Before Fred came along,” recalled Mr. Richardson, “Andy tended to see–I’m talking socially, not in terms of the artists–he saw a lot of lowlifes.”

One early member of Warhol’s circle, Valerie Solanis, was phased out the hard way–prison–after she shot and wounded Warhol and curator Mario Amaya, and reportedly pointed her .32-caliber pistol at Mr. Hughes. Lucky for him, the gun jammed.

When Mr. Hughes took over as the executor of Warhol’s estate, he was poised to realize his wish, but by then, he knew that the M.S. would eventually rob him of the dream. “Had he not been sick, he would have been one of the most powerful men in the art world,” Ms. Chermayeff said. “The combination of being on top and knowing that he wasn’t going to be able to stop this disease that destroys your body while your mind stays active, it was just too much.” Still, Mr. Hughes oversaw the extremely successful sale of Warhol’s furnishings, art and tchotchkes at Sotheby’s in 1988 and then the opening of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh in 1994. He also started the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which became the focus of Mr. Hayes’ legal battle.

In 1992, Mr. Hughes was forced out as chairman of the foundation. Friends say that the stress of all the litigation seemed to exacerbate his condition. The Texas aesthete who loved exploring the world and its treasures was steadily becoming a prisoner of his bed, kept from the stimulation that he craved. Friends continued to come to visit him, to talk to him or read to him, anything to keep him informed and up-to-date. Though he could not speak, “it was clear he took in everything,” Mr. Richardson said. “Sometimes the tears would pour down his face.”

“People who knew Fred in his prime were always grief-stricken after seeing him,” Ms. Chermayeff said. And sometimes Mr. Hughes helped them along. “He was in a rage,” she said. “For many reasons … the primary one was his frustration at the disease …. He just went down with a self-destructive fervor that was really hard to understand. It was as if he decided there would be no fizzling out.” But Ms. Chermayeff said that she suspects he may have been difficult for a reason. “He made it so I had a certain kind of freedom from him,” she said. “He freed us all from the suffering that everybody would have felt at seeing him suffer. I don’t know if it was conscious or subconscious.”

But maybe there was a precedent.

Vincent Fremont remembered that the summer after Warhol died, he and his family spent some time with Mr. Hughes in a house he had rented on Shelter Island. “I remember one time we found a dead squirrel or something like that,” Mr. Fremont said. “My daughters were pretty young and they got upset. Fred did this whole elaborate funeral procession.” Mr. Fremont paused a moment, as if he were trying to reconcile the Fred Hughes whom he’d accompanied from party to party until the sun came up in Paris with the man in this anecdote. “We went in a little line and dug a hole.” Mr. Fremont paused once more, perhaps wondering why Mr. Hughes, the New York Character, did not get a procession of his own. His voice grew faint, then recovered.

“I found him really charming,” he said. “And he wasn’t wearing a tie.”

About the artist:

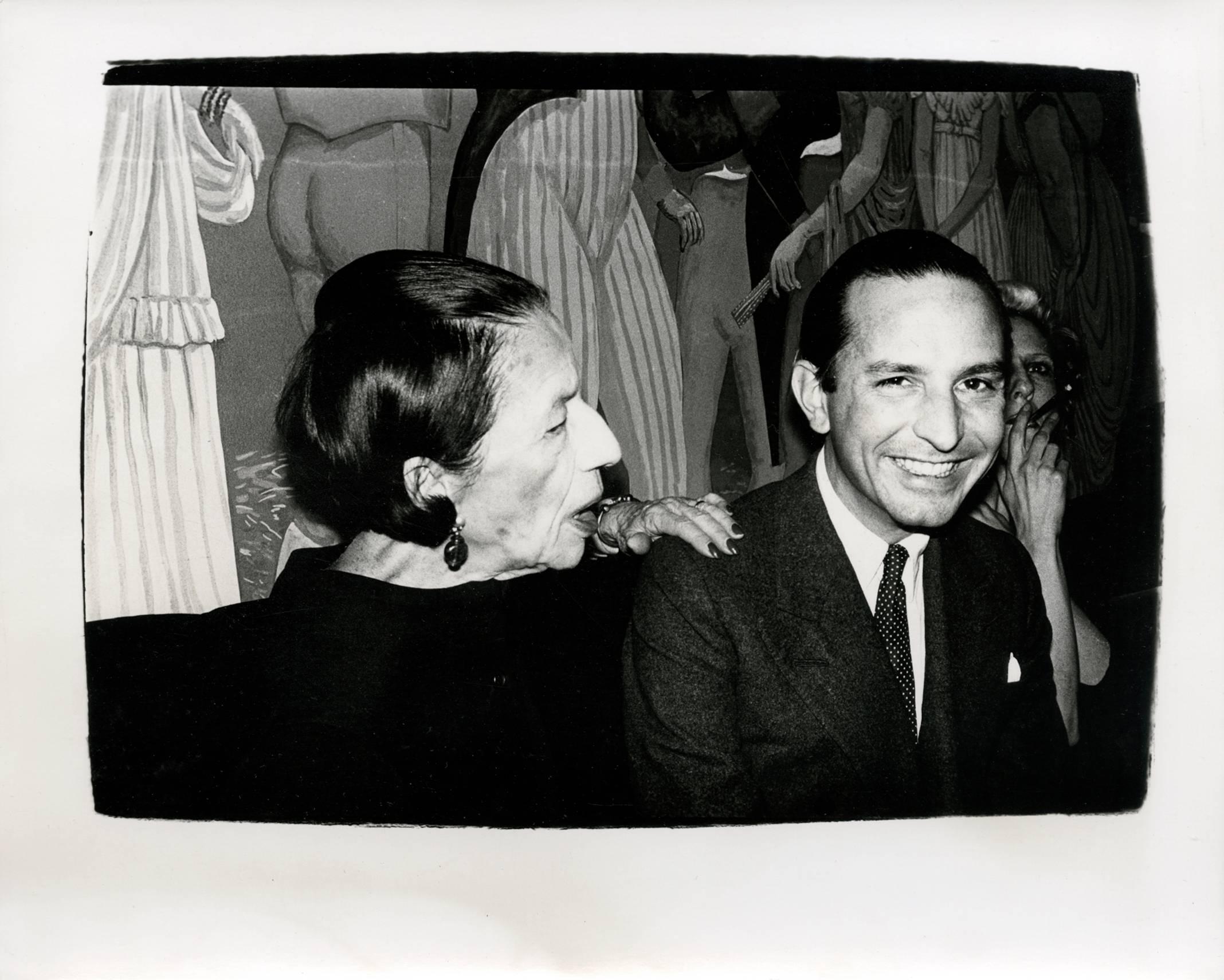

David Gamble is a multidisciplinary artist from London, now based in New Orleans. His body of work consists of paintings, works on paper, and photographs, all of which have been exhibited globally. Throughout the 1980s and '90s, Gamble worked as one of the foremost international editorial photographers for publications such as The Observer, The Independent, LIFE, Fortune, The New Yorker, Newsweek, Paris Match, The Sunday Times, and many more.

Over his decades-long career spanning the editorial, journalistic, and fine art realms, Gamble has photographed such illustrious figures as Stephen Hawking and the Dalai Lama with several of his portraits included in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. In 1987, Gamble won the Kodak Award for Best Photographer in Europe as well as a World Press Photo Award in 1988 for his portrait of Stephen Hawking, which was featured as the notable cover of Hawking’s A Brief History of Time.

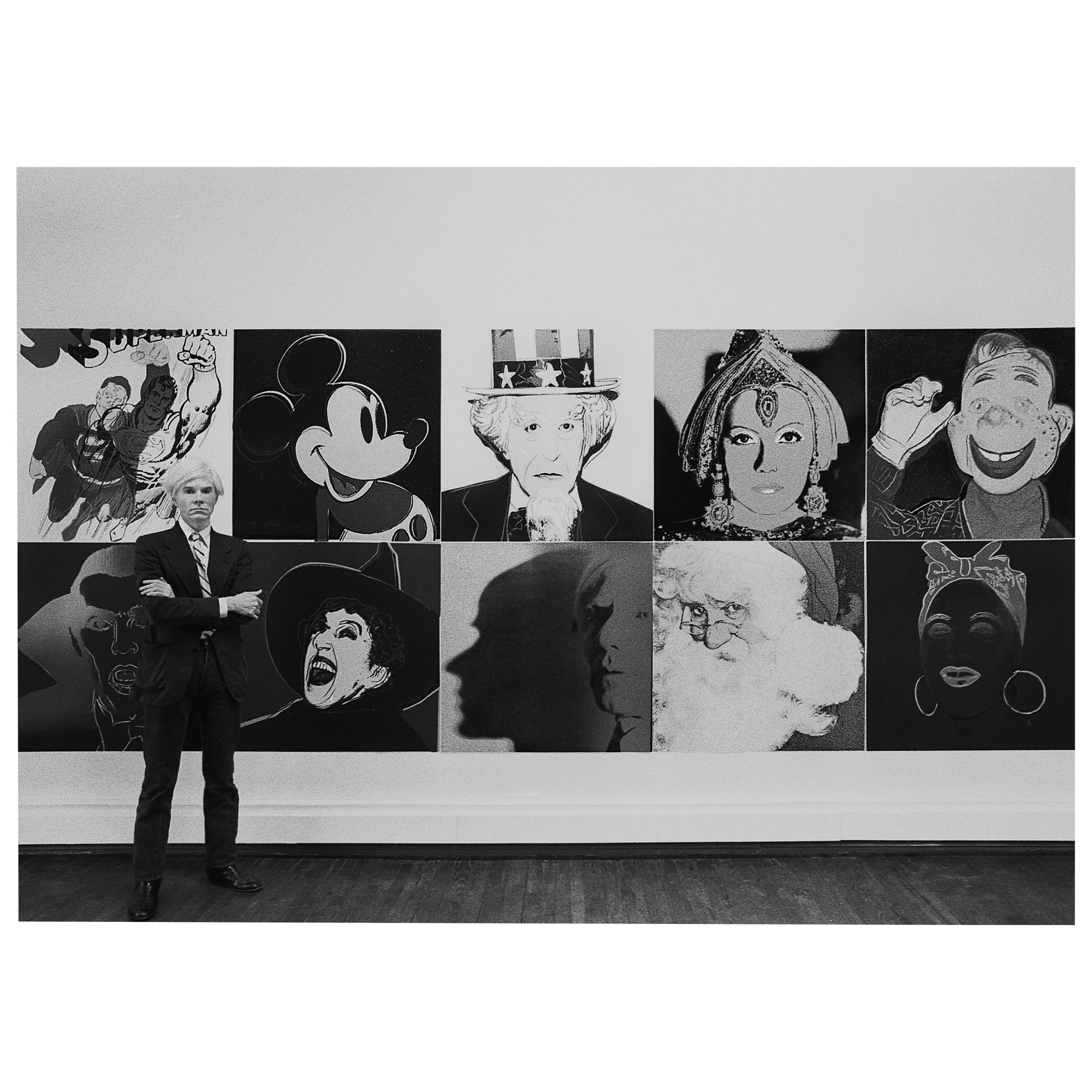

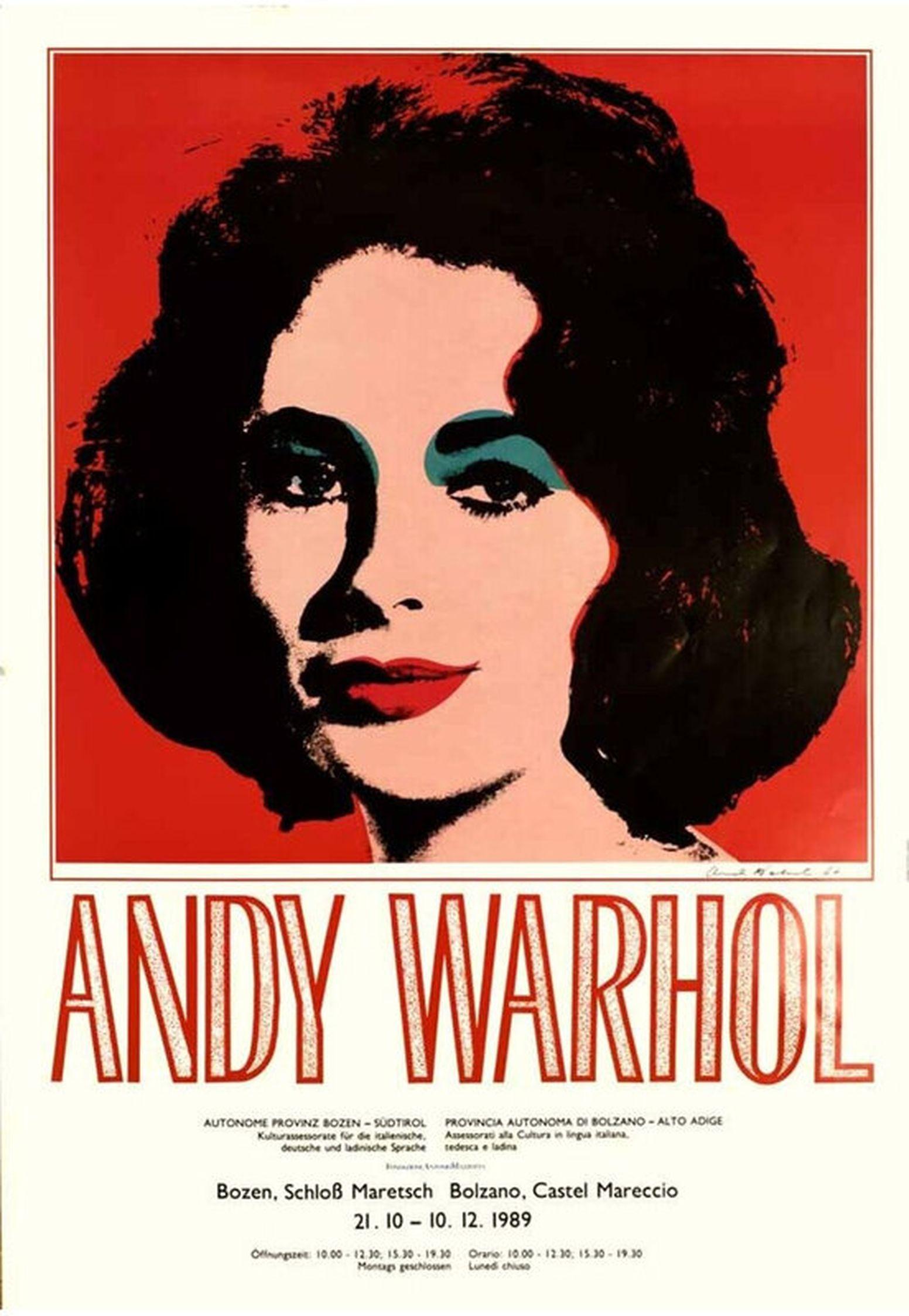

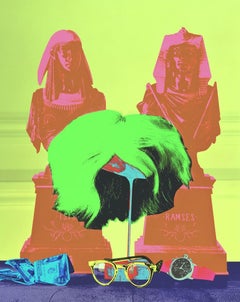

In 1988 Sotheby’s New York hosted one of the most talked-about auctions of the decade, the sale of the Estate of Andy Warhol. In addition to paintings and sculpture, some of the most hotly sought- after items were Warhol’s personal effects, including, décor, clothing, and even his 1974 Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow. The goal of the sale was to raise funds for the then fledgling Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Soon after Warhol’s death photographer David Gamble was permitted access to Warhol’s East 66th street House, Factory and Warehouse. There, he captured the placement of Warhol’s belongings as the artist had lived with them over the years. Rather than simply documenting the space, Gamble’s careful still-lifes capture the humanity and fierce individuality of the artist.