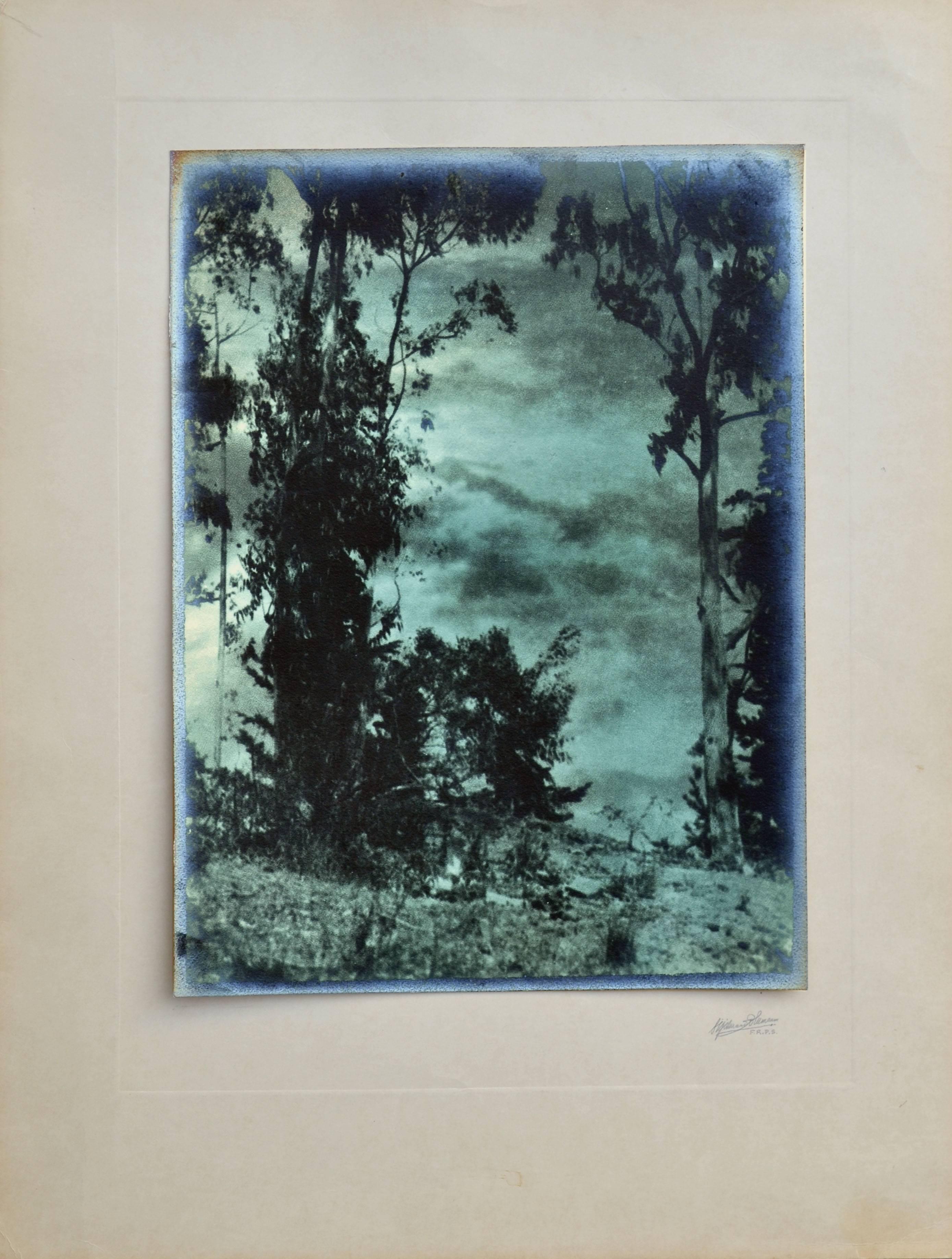

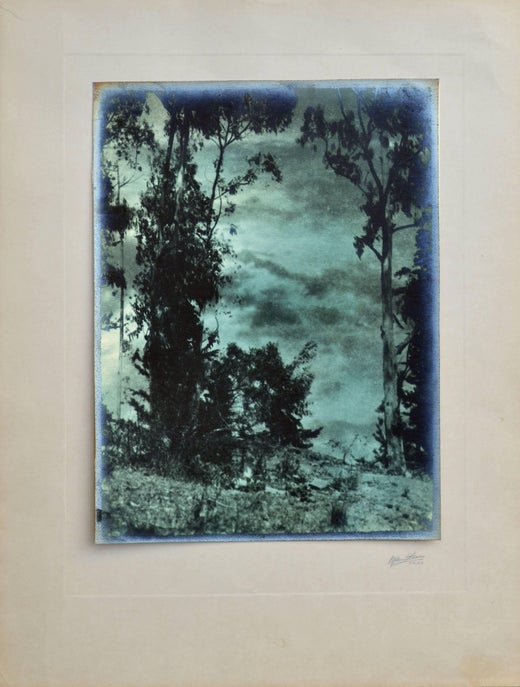

Sigismund Blumann"A Dance in the Moonlight" - Landscape Lithobrome Photograph1920

1920

About the Item

- Creator:Sigismund Blumann (1872 - 1956, American)

- Creation Year:1920

- Dimensions:Height: 20 in (50.8 cm)Width: 16 in (40.64 cm)Depth: 1 in (2.54 cm)

- Medium:

- Movement & Style:

- Period:

- Condition:some age toning to mat.

- Gallery Location:Soquel, CA

- Reference Number:Seller: JT-j31461stDibs: LU5421410643

Sigismund Blumann

Sigismund Blumann was a prominent tastemaker in Californian photography during the 1920s and 1930s. Based in the San Francisco Bay Area for his entire career, he edited magazines, wrote books, and made creative photographs. Between 1923 and 1932, his pictures were accepted at photographic salons in Amsterdam, Toronto, Rochester, Seattle, and Los Angeles. In 1927, a one-person exhibition of his bromoil prints traveled to camera clubs in Chicago, Akron, Cincinnati, and New York. In addition to bromoil, a process that yields pointillistic images, Blumann utilized such unusual processes as kallitype (Vandyke brown), lithobrome, and pastelograph (the latter two were probably his inventions) to create original photographs using chemical processes he invented.

From 1924–33, Blumann edited Camera Craft, the leading West Coast photographic monthly. Subsequently, he established his periodical, Photo Art Monthly, which he published until 1940. In these two magazines — for over 15 years — Blumann found a large audience of mainstream pictorial photographers. Besides, he wrote five instructional books on photography, providing a substantial amount of technical information for committed picture makers. During the 1920s, Blumann also made accomplished pictorial photographs of his own, concentrating on landscape work. In August 1924, Blumann was appointed editor of San Francisco’s Camera Craft (begun in 1900) and, at 52 years of age, began working in photography full time. He continued most of its regular columns, covering professional photographers, camera clubs, technique, and amateur troubles. Blumann was the magazine’s most prolific author during his nine-year tenure, writing nearly 130 signed articles and, presumably, most of the unsigned ones. The magazine included his monthly editorials, reviews of books and exhibitions, and feature articles on the laws of art, different processes, the difficulty of nude subjects, and pictorialists such as Léonard Misonne and William Mortensen. Blumann paid attention to professional photographers by running profiles on them, covering activities of their national and regional organizations, and addressing specific topics like advertising photography. And he consistently maintained a populist and positive attitude, running monthly competitions and including many of his poems. Blumann edited his last issue of Camera Craft in August 1933, but within a few months had started up his periodical, Photo-Art Monthly. With the help of only one assistant, he ran this magazine for the next seven years, carrying a very heavy load of writing and editing. The most notable changes were more attention to "artistic" photography (as suggested by the title), less coverage of professional photography, and increased anti-modernist attitudes.

In 1937, Blumann opened a gallery in the magazine’s offices, providing an exhibition venue unique in the country, where both group and solo shows of about 100 photographs were presented. Somehow Blumann found the time while he was an editor to write five manuals on photographic technique. Camera Craft published the first one in 1927—his Photographic Workroom Handbook, which went into four editions and sold over 60,000 copies. In the 1930s, he self-published a reworking of this title plus books on enlarging, toning and photographic greeting cards. Claiming that his calling was as a critic, Blumann downplayed his ability as a photographer, yet he achieved modest success as a pictorialist. He enjoyed being outdoors with his camera and turned it primarily on the natural environs of Oakland and California’s state parks and national forests. Reproductions of his work appeared in Camera Craft (both before and during his editorship), Photo-Art Monthly, and the American Annual of Photography 1927. In 1933, he was a charter member of the Photographic Society of America and received fellowship status from the Royal Photographic Society (FRPS). Sigismund Blumann’s last known photographic appearance was in the December 1943 issue of Popular Science, for which he wrote an illustrated article on toning black-and-white prints.

- ShippingRetrieving quote...Shipping from: Soquel, CA

- Return Policy

More From This Seller

View All1920s Realist Landscape Photography

Photographic Paper, Silver Gelatin

1870s Realist Black and White Photography

Photographic Paper, Ink, Silver Gelatin

1920s Realist Black and White Photography

Photographic Paper, Silver Gelatin

Late 20th Century Photorealist Landscape Photography

Photographic Paper, Silver Gelatin

Early 20th Century American Realist Landscape Prints

Paper, Ink, Drypoint, Etching

1920s Realist Landscape Photography

Photographic Paper, Silver Gelatin

You May Also Like

Early 1900s Realist Landscape Prints

Etching

1910s Modern Figurative Photography

Photographic Paper

20th Century Modern Figurative Photography

Photographic Paper

19th Century Black and White Photography

Photographic Paper

Mid-20th Century Modern Figurative Photography

Photographic Paper

Early 20th Century Modern Figurative Photography

Photographic Paper