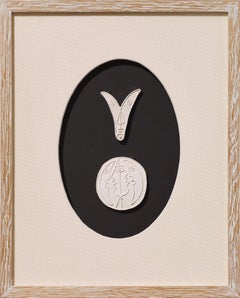

By Waylande Gregory

Located in Wilton Manors, FL

Waylande Gregory (1905-1971).

Nude Reclining, ca. 1950's. Painted composite cast from original sculpted in 1930's. Casting sanctioned and approved by the artist during his lifetime in partnership with MPI, Museum Pieces Incorporated. Very few examples were produced and even fewer survive.

Waylande Gregory was considered a major American sculptor during the 1930's, although he worked in ceramics, rather than in the more traditional bronze or marble. Exhibiting his ceramic works at such significant American venues for sculpture as the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City and at the venerable Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, he also showed his ceramic sculptures at leading New York City galleries. Gregory was the first modern ceramist to create large scale ceramic sculptures, some measuring more than 70 inches in height. Similar to the technique developed by the ancient Etruscans, he fired his monumental ceramic sculptures only once.

Gregory was born in 1905 in Baxter Springs, Kansas and was something of a prodigy. Growing up on a ranch near a Cherokee reservation, Gregory first became interested in ceramics as a child during a native American burial that he had witnessed. He was also musically inclined. In fact, his mother had been a concert pianist and had given her son lessons. At eleven, he was enrolled as a student at the Kansas State Teacher's College, where he studied carpentry and crafts, including ceramics.

Gregory's early development as a sculptor was shaped by the encouragement and instruction of Lorado Taft, who was considered both a major American sculptor as well as a leading American sculpture instructor. In fact, Taft's earlier students included such significant sculptors as Bessie Potter Vonnoh and Janet Scudder. But, Taft and his students had primarily worked in bronze or stone, not in clay; and, Gregory's earliest sculptural works were also not in ceramics. In 1924, Gregory moved to Chicago where he caught the attention of Taft. Gregory was invited by Taft to study with him privately for 18 months and to live and work with him at his famed "Midway Studios." The elegant studio was a complex of 13 rooms that overlooked a courtyard. Taft may have been responsible for getting the young man interested in creating large scale sculpture. However, by the 1920's, Taft's brand of academic sculpture was no longer considered progressive. Instead, Gregory was attracted to the latest trends appearing in the United States and Europe. In 1928 he visited Europe with Taft and other students.

"Kid Gregory," as he was called, was soon hired by Guy Cowan, the founder of the Cowan Pottery in Cleveland, Ohio, to become the company's only full time employee. From 1928 to 1932, Gregory served as the chief designer and sculptor at the Cowan Pottery. Just as Gregory learned about the process of creating sculpture from Taft, he literally learned about ceramics from Cowan. Cowan was one of the first graduates of Alfred, the New York School of Clayworking and Ceramics. Alfred had one of the first programs in production pottery. Cowan may have known about pottery production, but he had limited sculptural skills, as he was lacking training in sculpture. The focus of the Cowan Pottery would be on limited edition, table top or mantle sculptures. Two of the most successful of these were Gregory's Nautch Dancer, and his Burlesque Dancer. He based both sculptures on the dancing of Gilda Gray, a Ziegfield Follies girl.

Gilda Gray was of Polish origin and came to the United States as a child. By 1922, she would become one of the most popular stars in the Follies. After losing her assets in the stock market crash of 1929, she accepted other bookings outside of New York, including Cleveland, which was where Gregory first saw her onstage. She allowed Gregory to make sketches of her performances from the wings of the theatre. She explained to Gregory, "I'm too restless to pose." Gray became noted for her nautch dance, an East Indian folk dance. A nautch is a tight, fitted dress that would curl at the bottom and act like a hoop. This sculpture does not focus on Gray's face at all, but is more of a portrait of her nautch dance. It is very curvilinear, really made of a series of arches that connect in a most feminine way.

Gregory created his Burlesque Dancer at about the same time as Nautch Dancer. As with the Nautch Dancer, he focused on the movements of the body rather than on a facial portrait of Gray. Although Gregory never revealed the identity of his model for Burlesque Dancer, a clue to her identity is revealed in the sculpture's earlier title, Shimmy Dance. The dancer who was credited for creating the shimmy dance was also Gilda Gray. According to dance legend, Gray introduced the shimmy when she sang the Star Spangled Banner and forgot some of the lyrics, so, in her embarrassment, started shaking her shoulders and hips but she did not move her legs. Such movement seems to relate to the Burlesque Dancer sculpture, where repeated triangular forms extend from the upper torso and hips. This rapid movement suggests the influence of Italian Futurism, as well as the planar motion of Alexander Archipenko, a sculptor whom Gregory much admired.

The Cowan Pottery was a victim of the great depression, and in 1932, Gregory changed careers as a sculptor in the ceramics industry to that of an instructor at the Cranbrook Academy in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Cranbrook was perhaps the most prestigious place to study modern design in America. Its faculty included the architect Eliel Saarinen and sculptor Carl Milles.

Although Gregory was only at Cranbrook for one and one half years, he created some of his finest works there, including his Kansas Madonna. But, after arriving at Cranbrook, the Gregory's had to face emerging financial pressures. Although Gregory and his wife were provided with complimentary lodgings, all other income had to stem from the sale of artworks and tuition from students that he, himself, had to solicit. Gregory had many people assisting him with production methods at the Cowan Pottery, but now worked largely by himself. And although he still used molds, especially in creating porcelain works, many of his major new sculptures would be unique and sculpted by hand, as is true of Kansas Madonna. The scale of Gregory's works were getting notably larger at Cranbrook than at Cowan.

Gregory left the surface of Kansas Madonna totally unglazed. Although some might object to using a religious title to depict a horse nursing its colt, it was considered one of Gregory's most successful works. In fact, it had a whole color page illustration in an article about ceramic sculpture titled, "The Art with the Inferiority Complex," Fortune Magazine, December, 1937. The article notes the sculpture was romantic and expressive and the sculpture was priced at $1,500.00; the most expensive sculpture...

Category

1950s Art Deco François Pompon Art