Located in Wilton Manors, FL

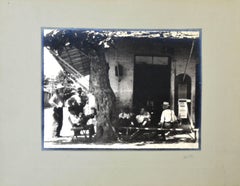

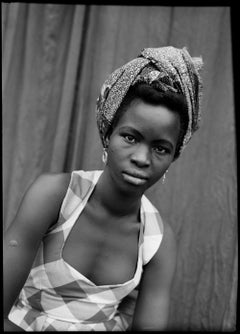

Portrait, ca. 1975. Period print measuring 8.75 x 11.25 inches. Unframed.

Studio stamp on verso.

Mounting and framing services available.

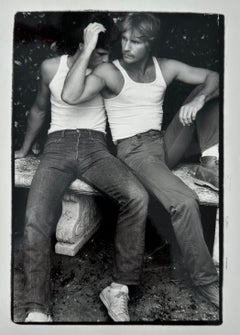

Victor Arimondi (November 8, 1942 – July 24, 2001) was an Italian American photographer and model who lived and worked in Europe before moving to the United States in the late 1970s. His early fashion photography, his portraits of Grace Jones and other artists, and his male nudes photographed in New York and San Francisco captured the pre-AIDS culture of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Arimondi's nudes were collected in several books, including David Leddick's award-winning[1] The Male Nude, (New York: Taschen 1998, 2005 and 2015). The photographer's later work documented homeless individuals in San Francisco's Tenderloin neighborhood and the toll of the AIDS epidemic on the city. His photographs, featured in several posthumous exhibitions, also are in the collections of Sweden's museum of modern art, Moderna Museet, and San Francisco's GLBT Historical Society.

Biography

Arimondi was born Vittorio Maria Tevitti to his unwed mother, Alessandra Calligaris, in Bologna, Italy on November 8, 1942. His mother struggled financially, which left an impression on her only child. In 1948, she temporarily left him at a children's boarding school and orphanage in Italy to move to Sweden for a job. There she met and married Bruno Arimondi, who adopted her son. The family returned to Naples, Italy in 1952 where Victor graduated from high school.[1]

In 1960, Arimondi returned to Sweden to study at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, although he did not graduate. Meanwhile, he worked at several blue collar jobs, including as a mailman, before he gave up on traditional full-time work to pursue what he considered more essential— a life of creative expression. He created costume-like clothing for himself and friends and at age 19 became a fashion model.

Even as a teenager, the Italian born photographer who spent his 20s and 30s primarily based in Sweden, noted that he preferred fantasy to the trials of real life.[1] That conflict, and his passion for beauty as well as his sexual energy, were major factors in his life and his work.[2]

From 1965 through 1972 Arimondi worked as model in London, Milan, Germany, New York and Stockholm, appearing in catalogs and fashion magazines including Vogue , Harper's Bazaar and Esquire and on the runway in several Valentino fashion shows.

In 1972 he decided to try working on the other side of the lens as a photographer to better express his creativity.[2]

Arimondi moved to New York in 1979 and continued to build his photography portfolio.

Portrait of Bearded Man, New York City, 1979

Two years later, in 1981, he moved to San Francisco where he lived and worked for twenty years until his death of AIDS at age 58 on July 24, 2001.

The year he moved to San Francisco, Arimondi opened a photo gallery in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood for a short time. When he struggled financially, he gave up on trying to earn a living through commercial fashion photography and closed the gallery.[3]

Arimondi returned to modeling for the financial benefits, though he did so on less of an international scale than in his early years.

He continued to create photographic portraits of the denizens of the San Francisco gay and arts cultures, to shoot male nudes and publish his work in magazines, and he began to compose and photograph evocative still lifes using his own photographic images. Many of them touched on the death of dozens of his former photography models from AIDS.

Arimondi was in the midst of a new photography project that brought together his background as a fashion photographer and his more recent social documentary work when he died several months after he learned he was HIV-positive.[4] The project featured his former colleague, haute couture cover model Ivy Nicholson,[5] who he found living homeless in San Francisco. Several of the haunting portraits he took of her were later included in a noted group exhibit at SF Camerawork.

Art

Arimondi's early photography in the 1970s in Stockholm included portraits of the stars of Sweden's fashion, theater and dance worlds. His first two photography exhibits were in Stockholm and met with mixed reviews. But as he matured as a photographer and tapped into his fashion world contacts, Arimondi landed a number of commercial fashion jobs, including shooting for the Italian designer Salvatore Ferragamo S.p.A.'s I.Magnin department store ad that ran in Vogue.

Marlboro Man Nude, New York City,1980.

He also shot other artists and models for his own portfolio, including Grace Jones, the Norwegian actress, Liv Ullmann, and the American writer, Norman Mailer.

Arimondi's aesthetic vision was focused on fantasy and drama, and he prided himself on pushing limits.[6]

Although less well-known than his San Francisco contemporary...

Category

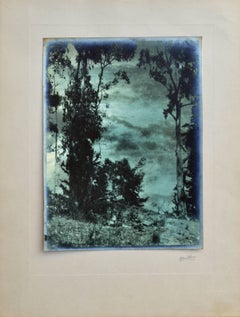

1970s Realist Sigismund Blumann Photography

MaterialsPhotographic Paper