March 30, 2025Some call the works on view at Etage Projects conceptual. Some call them political. Maria Foerlev, owner of the airy Copenhagen gallery, calls them poetic. “What I usually say to justify showing these strange — to some people — things is ‘The world doesn’t need another chair, but we do need poetry.’ ”

The “strange things” Foerlev purveys in her high-ceilinged white space in the city center are the otherworldly imaginings of an international assortment of contemporary artists and designers. Since founding the gallery, in 2013, she has championed such multidisciplinary talents as Thomas Poulsen, known as FOS, whose practice ranges from lamps and glassware to interiors for the Danish prime minister’s residence and shops for the French fashion house Celine; Sabine Marcelis, the prolific Dutch designer of lighting, furniture and fashion; and Soft Baroque, the London-based design duo responsible for furnishings and other domestic objects of intriguingly unfamiliar form. Some past installations have been highly unorthodox, even discomfiting, like the Spanish artist Guillermo Santomà’s hair salon, oozing pink foam; an array of clothing made of petrochemical waste by Victor Miklos Andersen and Aske Hvitved, intended as a critique of Denmark’s role as a top EU oil producer, as well as of its fast-fashion industry; and a display of bulbous molded-resin chairs by Anna Aagaard Jensen that encourage women to sit with splayed legs, taking up maximum space.

For all her gallery’s avant-garde leanings, Foerlev hails from a family firmly grounded in classical Danish design. Her great-grandfather, Rudolph Christensen, built a Victorian home in Copenhagen with such bells and whistles as electricity and a flush toilet; it’s now part of the Danish National Museum. And she grew up in a house designed by legendary mid-century architect Arne Jacobsen, husband of Foerlev’s Aunt Jonna, a textile designer.

After studying design and art history at Sotheby’s in London, Foerlev was briefly an architecture student at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, then ran a drawings gallery and a store selling toys by Austrian philosopher and educator Rudolph Steiner. About a dozen years ago, she rented a small space in a 1940s building by Danish architect Kay Fisker, where she sold Gerrit Rietveld licensed furniture. “In the next room worked a designer from Eindhoven academy,” one of Europe’s preeminent design schools, Foerlev recalls. “He told me about the conceptual approach they teach there, which really appealed. I started curating shows and, after some time, managed to take over the whole space.” Today, her 2,000-square-foot gallery mounts as many as 10 exhibitions a year, challenging visitors to question everything they thought they knew about art and design.

Foerlev spoke with Introspective about why she gives artists free rein, the conceptual underpinnings of Etage Projects’ offerings and the best museums to visit for contemporary design.

I know you resist labels, but how would you describe the material in your gallery?

The urge to understand things makes us come up with words and categories. Words can be a valuable tool, but they don’t really matter. Our emotional apparatus isn’t able to differentiate whether something is architecture, design or art. I think people should use labels as they want. What is important is moving, and being moved. Most of the pieces in the gallery call for human interaction in order to understand their real value.

You use the phrase “cross-aesthetic method” on your website. What do you mean by that?

I work with artists who create functional objects, and designers and architects who work conceptually. That is crossover, because in the marketplace, design and art lead pretty separate lives. Some artists don’t want to, and shouldn’t, have the client in mind while creating. Some designers should just focus on function and nothing else.

Can you tell us about the approach you take in working with an artist or designer?

The designer or artist is free to experiment. The works I like to present are not filled with compromises. When a designer cuts loose from the demands and practical implications of the mass market, it can result in design with a strong connection between process, material and form, where craftsmanship, poetry and conceptual values are joined.

How did you come to be interested in such avant-garde material? What factors in your educational background or career led you to be doing exactly what you’re doing?

I am just curious and interested in different perspectives. Lucky for me, I have met wonderfully talented people who have them. I love finding an interesting theme and bringing together works by different artists that when assembled are both aesthetically and intellectually pleasing.

I remember when I was studying in London, auction houses began presenting art-and-design sales. That made so much sense to me. Marc Newson’s Lockheed chaise longue sold for an astronomical amount. Coming from Denmark, where the golden age of design is considered to have been the nineteen fifties, it was such a breath of fresh air.

Do you live with any of the pieces from your gallery? Which would you spotlight as functional objects that can be used in a domestic setting?

I almost only live with works from the gallery. I have a lamp made of three coconuts. My dining chairs have handprinted canvas seats. My storage is made of OSB [oriented strand board, a type of engineered wood] and silk made to look like OSB, by Soft Baroque.

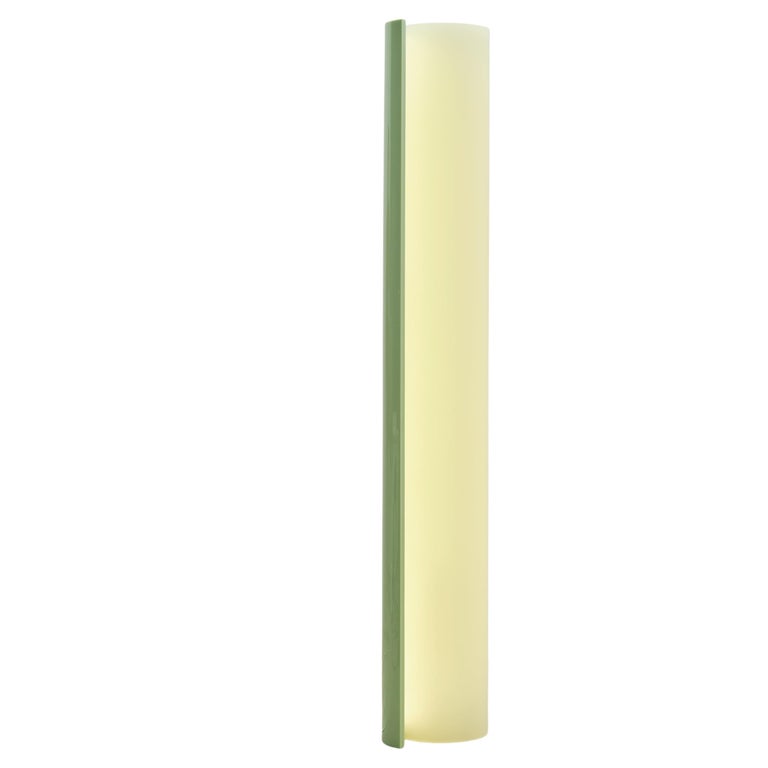

Sabine Marcelis’s Candy Cube tables, her Hue mirrors and sculptural resin pieces from her SOAP furniture collection are ultra functional. They have the ability to fit any interior and enhance it.

How can people who are interested in learning more about contemporary design educate themselves further?

I suggest books like AC/DC: Contemporary Art/Contemporary Design and Bruno Munari’s Design as Art and visiting museums such as Triennale di Milano, Villa Noailles in Hyères, France, and Odunpazari Modern Museum (OMM) in Turkey. Finally, go to a gallery and ask questions! Most gallerists are more than happy to explain.