March 21, 2021“If you’re interested in thinking about the history of previously marginalized demographics, then you’re almost compelled to think about craft history,” says Glenn Adamson, who, together with Jen Padgett, co-organized “Crafting America” at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Encompassing 121 objects produced in the United States by 100 artists from the 1940s to the present, this survey of “skilled making on a human scale,” as the curators define craft, foregrounds women, people of color, immigrants and indigenous practitioners of this discipline, often considered of a lesser status than fine art.

Rather than make a binary distinction between craft and fine art, the show explores a broad spectrum of work — including pieces by contemporary creators, such as Ebony G. Patterson, Nick Cave and Arlene Shechet, who don’t necessarily identify as craftspeople — through the lens of craft.

“I think of craft as a major variable in design, in fine art, in architecture,” says Adamson, a former director of New York’s Museum of Art and Design, who now works as an independent curator and art historian.

Here, woman-made fiber art is paired with masculine ceramics, all from the mid-20th century (from left): The Principal Wife, 1968, by Sheila Hicks; Rondena, 1958, by Peter Voulkos; Orinoco, 1967, by Lenore G. Tawney; Spear Form, 1963, by John Mason. Photo by Ironside Photography / Stephen Ironside.

The show (on view through May 31) spotlights five key materials in modern American craft: fiber, ceramics, metal, glass, wood. It begins its examination with the studio craft movement as it was gaining steam in the years surrounding World War II.

“There were a number of factors that went into that, from the immigration of artists from Europe who were trained in all sorts of disciplines,” says Padgett, an associate curator at Crystal Bridges, noting the influence of Anni Albers in weaving and Marguerite Wildenhain in ceramics, both of whom studied at the Bauhaus in Germany.

“There are also artists who served in World War II and attended school afterward through the GI Bill,” the curator adds. The Native American modernist jeweler Charles Loloma, for instance, went to the School for the American Craftsman in Rochester, New York, on the GI Bill and took up metalwork when he returned home to the Southwest.

Clockwise from lower left: Soundsuit, 2009, by Nick Cave; Vase with Dragon, 2020, by Steven Young Lee; In Numbers Too Big to Ignore, 2016, by Jeffrey Gibson; Untitled (Four-Lobed Continuous Form), ca. 1958, by Ruth Asawa; bugs, reptile, fruit and bush . . . for those who bear/bare witness, 2018, by Ebony G. Patterson; Architectural Coil Maquette, 2011, by Hoss Haley; and Frederick Douglass / Arthur Ashe Urn, 2017, by Roberto Lugo

With works grouped under the headings “Life,” “Liberty” and “The Pursuit of Happiness” — aligning craft practices with key tenets of American identity — the first section looks at everyday functional objects.

Pieces by great figures in woodworking — among them, Wharton Esherick, Bob Stocksdale and George Nakashima — are displayed here, as well as ceramics by such luminaries as Gertrud and Otto Natzler, who emigrated from Austria; the Finnish modernist Maija Grotell, who taught at Cranbrook, in Michigan; and Doyle Lane, one of the few African American figures in the studio craft movement.

Under the “Liberty” rubric, the show looks at makers who moved beyond utilitarian objects to more abstract forms, such as Sheila Hicks and Lenore Tawney, in fibers; and Peter Voulkos and John Mason, in ceramics.

“They made this strong adventurous move into sculptural terrain,” Adamson says. “It’s really about gesture, expression, individual vision.” The curators put contemporary artists like Shechet, Nicole Cherubini and Diedrick Brackens in dialogue with this earlier moment.

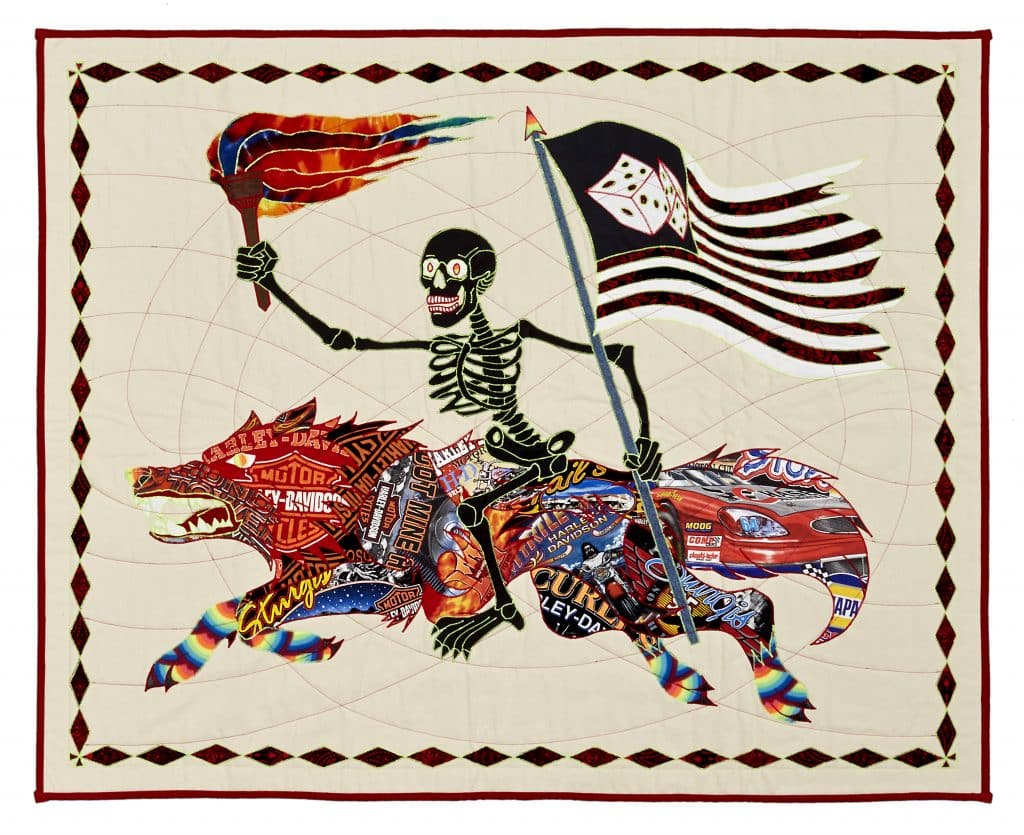

“Pursuit of Happiness,” the last big section of the exhibition, is the loosest, including work by Patterson and Cave along with other artists one wouldn’t necessarily expect to see in a crafts show. Among the pieces exhibited are Judy Kensley McKie’s anthropomorphized monkey chair, Darryl Montana’s flamboyant carnival costume, Andy Paiko’s magical blown-glass reliquaries and Kathy Butterly’s radically convoluted ceramic vessel, which has no discernible function other than the seductive qualities of her materials.

“ ‘Pursuit of Happiness’ has a sense both of the visual culmination to the show and of the imaginative, speculative, spectacular angle of craft,” says Padgett, “the engagement with the skill as the source of joy and exuberance.”

Part of the exhibition but sited in the permanent collection galleries are two additional installations. One is a special commission by the glass artist Beth Lipman, whom the curators invited to respond to the museum’s early American works. Colonial portraits of a Jewish family inspired Lipman to create a glass trunk that, lluminated from the bottom and filled with glass objects of varying transparency, speaks to the treasured things that people carry with them.

In another collection gallery, 11 ceramic sculptures by Toshiko Takaezu are grouped in the middle of a room whose walls are hung with paintings by female Abstract Expressionists, including Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Mitchell and Grace Hartigan. Takaezu used the vessels — some quite large and almost figural, all without openings — as three-dimensional canvases, painting their surfaces with calligraphic gestures.

A gallery of textile works (from left): Sarah Lockett’s Roses, 1997, by Ronald Lockett; In Numbers Too Big to Ignore, 2016, by Jeffrey Gibson; Home of the Brave, 2013, by Consuelo Jiménez Underwood; and Treaty with the Yankton Sioux, 1837, 2014, by Gina Adams. Photo by Ironside Photography / Stephen Ironside

“She was extremely conscious about her dialogue with the Abstract Expressionists,” Adamson says. “With Takaezu, it’s really about a union of this pure ceramic form and the activity of throwing as a meditation practice.”

Women make up more than half the artists in the show and, according to Adamson, have been among the real innovators in craft. “You couldn’t imagine textile history without Anni Albers, Lenore Tawney and Sheila Hicks,” he says, “or ceramics without Toshiko Takaezu.”

Female creators have led in textiles and ceramics from the early 20th century onwards. “The famous story everyone always uses,” says Adamson, “is that at the Bauhaus, if you showed up at the door as a woman, they would either send you to the metal workshop or the weaving workshop. That’s how Marianne Brandt and Anni Albers and Marguerite Wildenhain all ended up being craftspeople.”