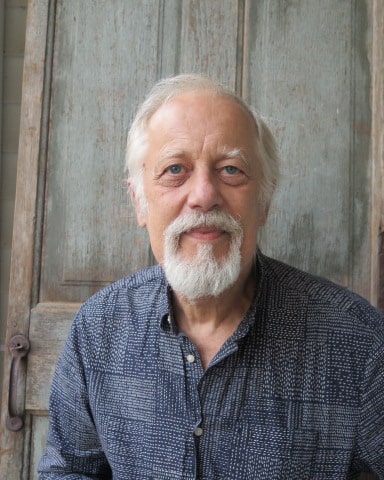

October 25, 2020For nearly five decades, Aarne Anton, of American Primitive Gallery, has been a lover of and expert in art objects variously termed primitive, folk, outsider or naive art. Anton is quick to make clear, however, that there is nothing remotely naive about the objects to which he has dedicated his career.

When he began in the field, in the early 1980s, there were few dealers focusing on tribal and American folk objects. Today, these pieces, whatever we elect to call them, are much sought after, rivaling and living harmoniously beside more mainstream contemporary art.

Growing up in the ’60s near Syracuse, New York, Anton was already drawn to raw, unpredictable beauty, obsessively collecting fossils and rocks. He therefore thought he’d major in geology in college, but a couple of years into his studies at the University of Rochester, he found he was less interested in analytics and mining rights and more interested in what captured his eye.

So he added art to his university curriculum, earning a BFA, and took classes at Manhattan’s School of Visual Arts, ending up with a phenomenal eye. He later developed a quite special ancillary skill: handcrafting beautiful bases in metal and wood for the tasteful and informed display of works by indigenous peoples.

It started as a part-time gig to make ends meet after college, but before long, Anton found himself designing bases to complement the non-Western art holdings of the American Federation for the Arts and Pace Gallery, in New York City.

As a base designer, Anton was exposed to the finest nontraditional objects and their proponents — Ricco/Johnson Gallery, Adelaide DeMenil and William Greenspon, renowned psychiatrist and fabled naive art collector. In the process, Anton says, he “just got hooked,” becoming an ardent student of the genre and a creative, even compulsive, buyer.

He couldn’t afford the museum-quality works, but he started to canvass the antiques stores and flea markets of upstate New York, amassing beautiful, unusual things, like carved hunting and fishing decoys and instruments fashioned by hand from wood.

Gorgeous oddities Anton bought for his personal pleasure began to attract attention, and key dealers in Americana unwittingly became regular patrons. “After a while, it got so important,” he says of his collection, “dealers would compete to see what I had picked up on a weekend treasure hunt and eventually to buy from me.”

Inevitably, the lucrative base-design business gave way to his first successful gallery, on 28th Street in New York City’s fur district, then a larger space in Soho and finally a noted gallery on 78th. Anton mounted about 10 folk-art exhibitions per year, featuring such creators as Lee Bontecou, Lonnie Holley, William Edmondson and Terry Turrell.

Today, he continues to collect and sell some of the finest examples of international outsider art from his home in Pomona, New York, whose tasteful decor rivals the contents of a museum. “Now, my house is both my gallery and my collection,” he says.

Anton recently spoke with Introspective about what outsider art means to him and how to recognize the genuine thing.

What motivated you to move from admiring to selling these objects?

Well, first off, when I got out of art school, it was during the rise of conceptual art, a genre where there’s great cross-pollination between painting and sculpture — a mixture of multiple styles, media and materials. That approach to visual objects told me that anything that is thoughtful, imaginative and made attentively can resonate with us and be art, even if it does not live within strict academic or classical standards.

But starting a gallery is expensive — it takes more than admiration.

I was already very much into this world, and in 1977, I happened on an antiques store that was about to open in the Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania, Shaker community. I found a Haida Indian tribal speaker’s staff, which I bought on pure instinct for $600. The staff was topped by a carved eagle decorated with abalone shells and crystal garnets.

Let’s just say I made enough from that intuitive buy to start my entire dealing business. It was clear I could make far more money as a dealer than producing bases, even at the height of my design studio.

Who have been some of your most noted clients?

There have been many, but someone I really enjoyed working with was Herbert Hemphill Jr., the founding curator of the American Folk Art Museum, who co-organized the 1970 exhibition “Twentieth-Century Folk Art” and coauthored the bible of the genre, Twentieth-Century Folk Art and Artists.

Is the term folk art reserved for objects that have been around for a while?

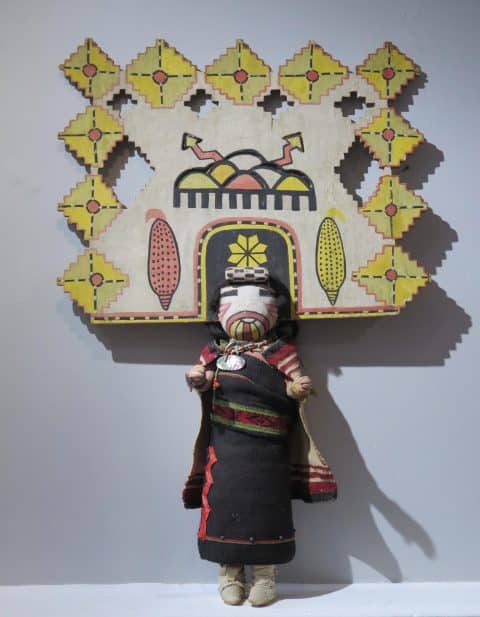

Not necessarily. There are current folk artists in major contemporary collections. Many collectors of contemporary art are also often collectors of American folk art. There’s a freedom and inventiveness shared by both.

Example?

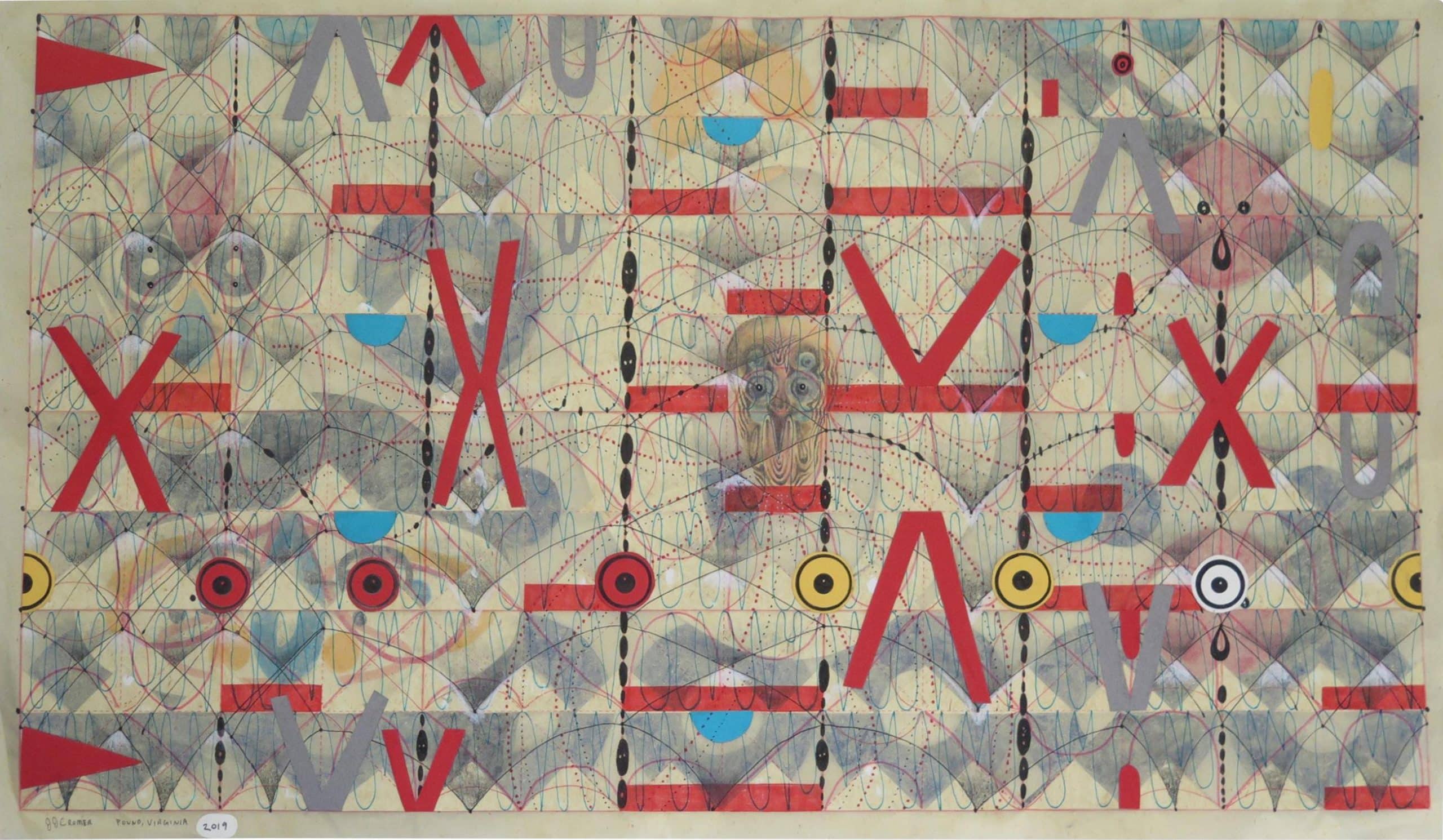

Purvis Young — his work fills my home. He started in Miami’s blighted Black Overtown neighborhood in the 1970s. He became interested in art in prison as a teenager and after that made thousands of drawings and paintings. His work is now in the Met.

An impressive compendium of outsider art was assembled for a recent show called “An Alternative Canon” at Andrew Edlin Gallery that featured folk art acquired by key collectors. Were you represented?

Yes, I selected two amazing animal works by the artist O.L. Samuels — a lion and elephant of painted wood and studded with so much glitz they look like they’re off to Mardi Gras. The elephant head hinges up to reveal a hidden “safe” for valuables. He is a remarkable artist.

The terms primitive and naive can sound pejorative, like this is work made by less educated, isolated people or — another frequent cliché — by the eccentric or the mad.

I prefer the term outsider art, and I use that label to describe work made by self-taught artists. That doesn’t mean they are necessarily uneducated. Many artists have skills or long-term jobs in other areas.

What I think characterizes them all is that they have this impulse that has nothing to do with the art market — the outsider artist makes all sorts of things out of some inner impulse and will make them no matter what. And the things they make have a remarkable directness, freshness and beauty somewhere between prehistoric cave art and children’s art.

Outsider art is open, inventive and without standards, but so is much hobbyist kitsch. How would you advise collectors of American folk art to recognize an object of value?

That’s tricky. Some folk art is anonymous, and some can be old. Its essence includes creators who work outside the so-called art canon, so often, there are no official records — until, of course, a good museum or dealer discovers the work, and then you rely on their expertise.

I’d say, seek out dealers, galleries, sellers that have a track record of knowing and respecting this type of art. Look at their vision and taste, and if it aligns with yours, trust them. But always let your eyes guide you.