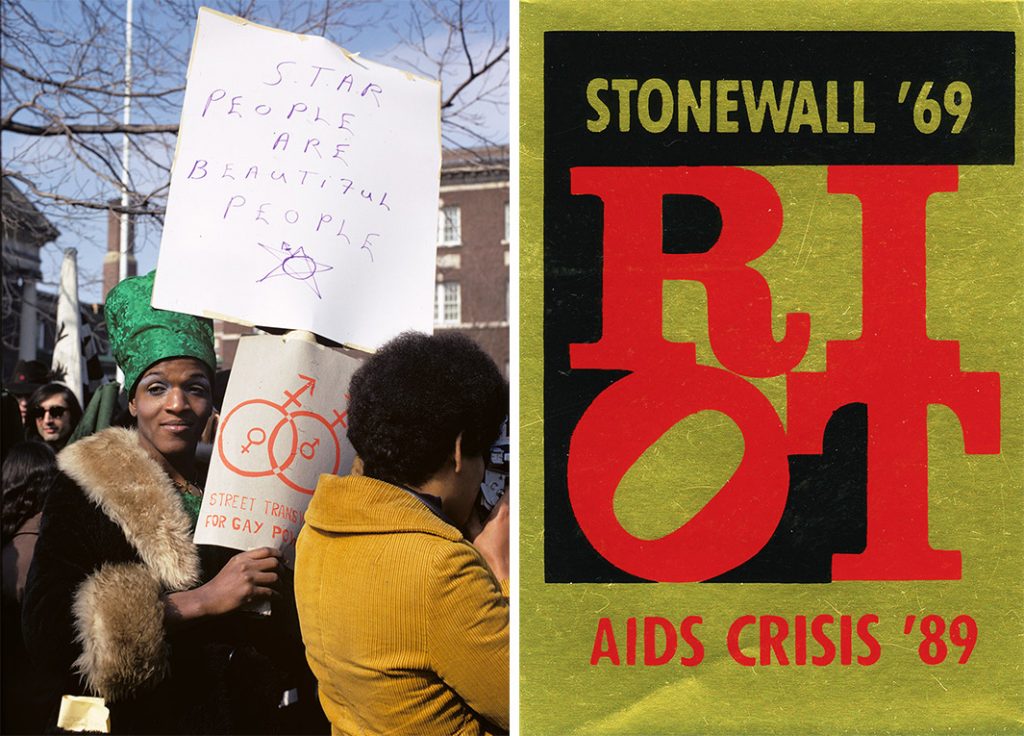

June 20, 2021Homosexuality and gender fluidity have appeared as subjects in art for millennia, but for modern Western cultures, it wasn’t until the late 20th century that artists could treat such themes overtly, without fear of censorship, ostracism or even arrest. The well-documented tipping point was June 1969, when a routine police raid on the Stonewall Inn — a bar in Greenwich Village known for drawing a gay, lesbian and transgender crowd — unwittingly gave rise to an ongoing groundswell of LGBTQ activism.

At the time, homosexuality was illegal in 49 states, gays and lesbians were barred from working for the federal government, and police treated cross-dressing as a punishable crime. Fed up with decades of discrimination and emboldened by civil rights gains made by other marginalized communities, the Stonewall’s customers resisted arrest and began rioting in the streets. Their efforts quickly drew allies, and five days of heated protests ensued.

The Stonewall rebellion, commemorated every June since 1970, ushered in an era of pride and openness, which gained traction and visibility, in part, through art and visual culture. “Pride was a reversal of shame, and there was long shame around being gay or gender-nonconforming. So, insisting on pride and LGBTQ visibility was a way to reverse that,” says Conor Moynihan, a curatorial fellow at the RISD Museum, who explains that the term queer, once a derogatory label, has been reclaimed as an umbrella phrase implying a resistance to the heteronormative status quo.

After Stonewall, from the 1970s on, art became a safe space where overtly gay, lesbian, trans, queer and nonconforming ideas, subjects and images could be freely explored. The queer art that has since evolved ranges from unflinching agitprop to intimate, personal reflections. To commemorate Pride Month and the work of LGBTQ artists, 1stDibs is donating to the nonprofit arts organization Queer|Art 15 percent of proceeds from sales of the artworks in our PRIDE COLLECTION.

Here, Introspective takes a look at some of the most impactful examples of LGBTQ art making, from before Stonewall to today.

Pre-Stonewall: Communicating by Code, Flouting Convention or Hiding from Public View

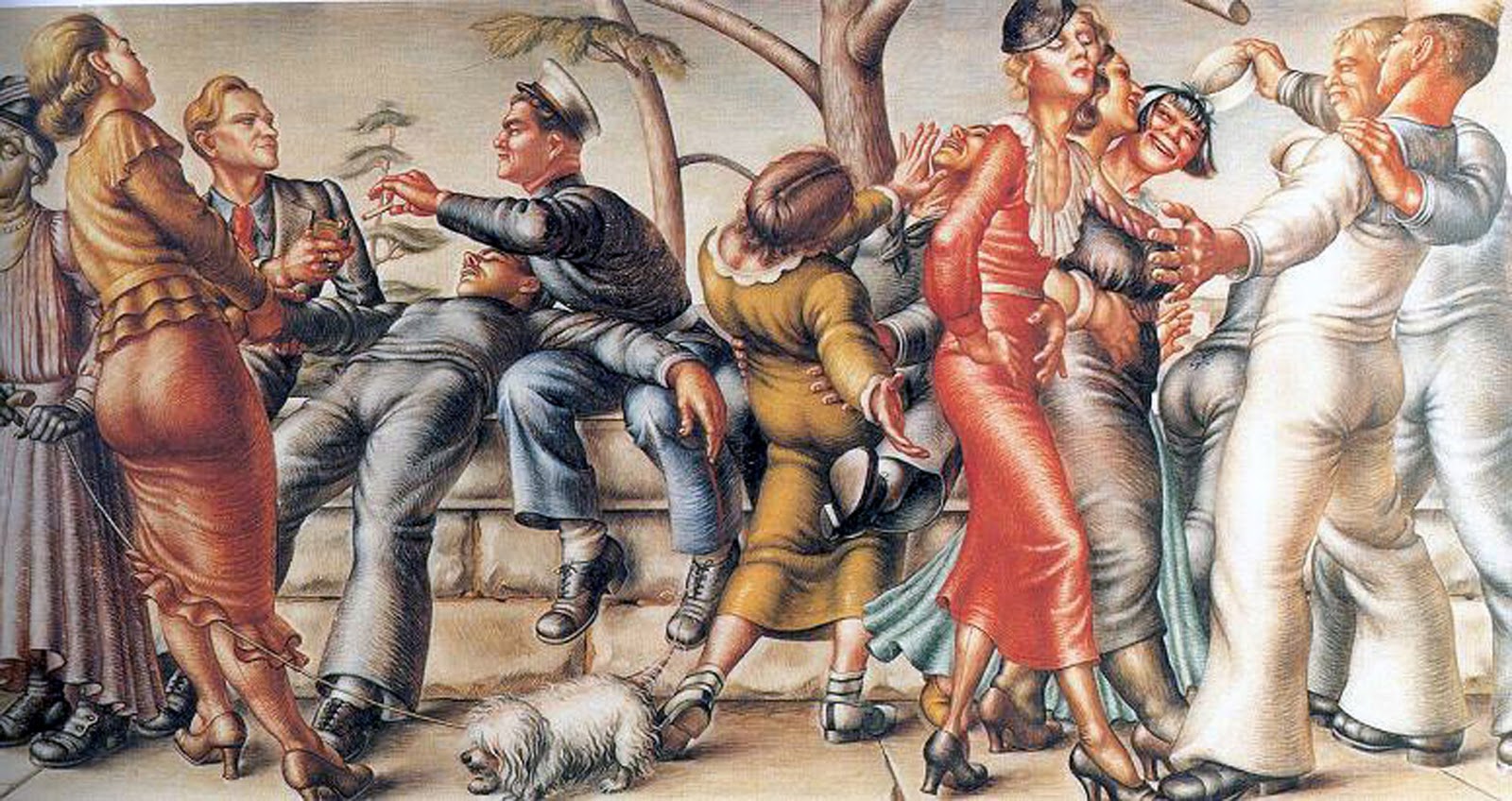

The long history of homophobia in the Western world didn’t keep homosexuality out of art, necessarily, but it did drive artists to conceal their sexual preferences behind visual codes. In his 1934 painting The Fleet’s In, for instance, Paul Cadmus caused a national scandal with his depiction of drunken sailors carousing with women, but that hetero action is, in effect, a clever distraction from the homoerotic innuendo of the sailors’ buttock-clinging pants. And who is the dapper civilian man with wavy blond hair, wearing a suit and tie? “There are coded symbols in the way the man is dressed: The red tie, the slicked-back hair and the transactional exchange of a cigarette — these are indications that this man is soliciting sex,” says Moynihan.

Experimenting with modernist tactics, Marsden Hartley used abstracted symbols to convey his queerness, while Charles Demuth kept his watercolor depictions of gay subculture in the 1930s private. These were essential strategies if an artist wanted to make it into mainstream museums or galleries.

Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg understood this as they ascended the avant-garde ranks in New York City. “They made some references in their work, but they were closeted because they wanted success,” says Brian Paul Clamp, of the New York gallery ClampArt.

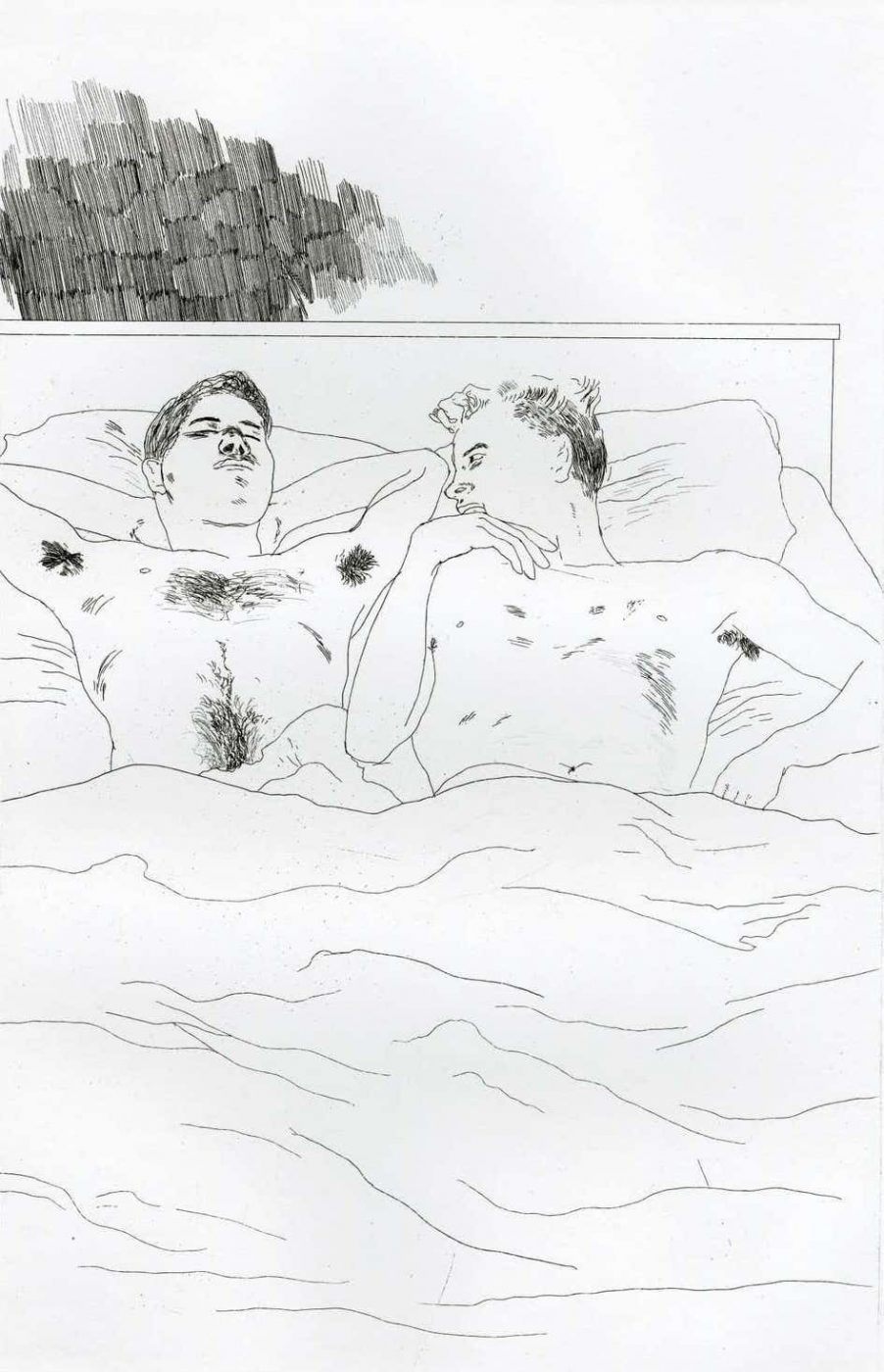

The young Andy Warhol, in contrast, refused to give in to those pressures even as he pined for recognition as a fine artist — and met one rejection after another when he presented dealers with his drawings of young men kissing. DAVID HOCKNEY, likewise, proudly portrayed homoerotic scenarios in his early drawings of the 1960s. FRANCIS BACON, who was notoriously kicked out of his parents’ house when his father caught him trying on his mother’s clothes, did not flaunt his homosexuality, but he also did not hold it back in his art. He was painting distorted, fleshy images of nude men — sometimes writhing together — that were clearly erotic, even in their abstraction, as early as the 1950s, when such imagery was intensely transgressive.

Other creatives’ work was discovered only much later in the 20th century, after societal attitudes toward homosexuality had changed.

French artist and writer Claude Cahun, who addressed her own gender ambiguity in experimental photographs and claimed that “neuter is the only gender that always suits me,” was well-respected in Surrealist circles in Paris in the 1920s and ’30s, but her work wasn’t publicly exhibited until the 1990s, when academia and the art world began taking a keen interest in identity politics and gender studies.

For his part, the esteemed gay fashion and portrait photographer George Platt Lynes felt compelled to hide a critical chunk of his oeuvre — hundreds of male nudes — from the public, even though he considered them his best work.

Stonewall’s Wake: Gay Liberation, the Sexual Revolution and the Photographic Image

Energized by the gay liberation movement and the growing sense of acceptance and community following the Stonewall rebellion, artists in the 1970s and early ’80s depicted gay, lesbian and transgender subjects with an unprecedented openness. “Before the civil rights movement, it was illegal to even mail full-frontal nude male images through the post,” says Clamp. “That changed. There was the sexual revolution and other developments that allowed these artists to be more openly gay and more openly sexual.”

Photography emerged as a particularly crucial vehicle for increasing lesbian and gay visibility, as such artists as Robert Mapplethorpe, Peter Hujar, Nan Goldin, Bill Jacobson, Mark Morrisroe and Jack Pierson turned their lenses on the LGBTQ life unfolding around them, poetically documenting their friends, lovers and nightlife with the kind of intimacy afforded only to insiders.

“There was a big drive to document gay and lesbian and transgender communities and subcultures and individuals, and the camera was readily available to do that,” says Jonathan Weinberg, curator and director of research at the Maurice Sendak Foundation and the curator of the 2019 show “Art after Stonewall: 1969– 1989” at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art.

At the same time, numerous lesbian photographers rethought conventional representations of women through the lens of feminism while also reenvisioning lesbian erotica for women. The highly influential Tee Corinne, for instance, famous for her 1975 Cunt Coloring Book of vulva drawings, explored lesbian sexuality through solarized photographs of nudes that formally channeled Man Ray but pictured ordinary and underrepresented female bodies, including those of older, overweight and disabled women, as well as women of color.

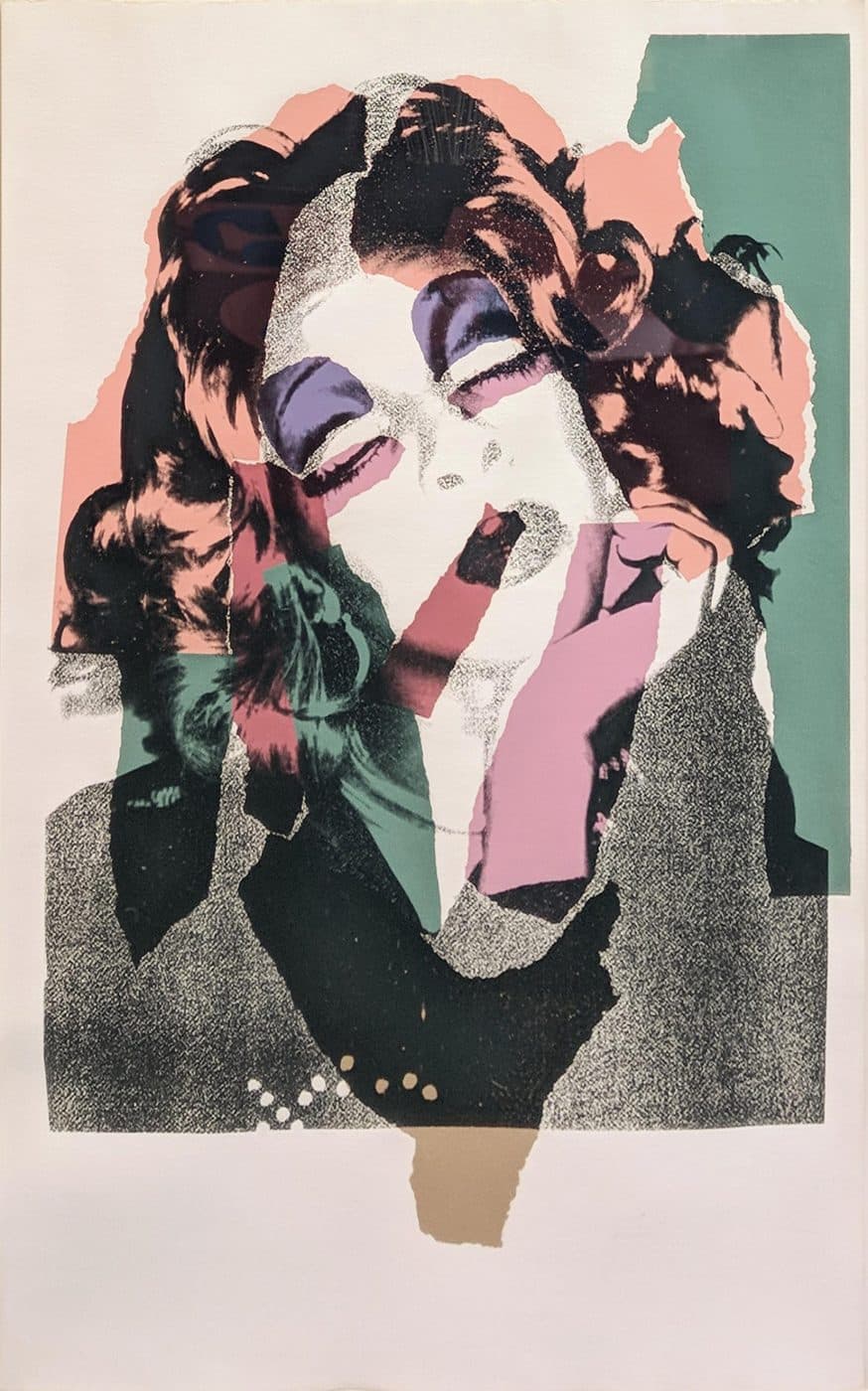

Warhol gave us glimpses of the underground queer scene in his 1960s Polaroids of superstars Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis and, later, in his notorious 1975 commissioned series of Black and Brown drag queens, “Ladies and Gentlemen” (which happened to feature the LGBTQ activist Marsha P. Johnson). But in his “Sex Parts and Torsos” photographs — sexually explicit closeups of mostly male bodies — we get perhaps the most visible sense of his interest in sexuality.

As dealer Jim Hedges, of Hedges Projects, explains, Warhol had Victor Hugo, his assistant, bring men to the Factory so he could photograph them: “Warhol would make these images —never getting himself dirty, always separated by the camera — of every fetishistic thing one could imagine with gay men. And like with oxidation paintings and cum paintings, where he’d have guys urinate or ejaculate on the canvas, he’d turn everything into a Pop image that a rich lady could have in her Fifth Avenue apartment.

“All of Warhol’s forms of work,” Hedges adds, “are an expression of queerness — not only in the homosexual-desire category. He had a fundamentally queer way of thinking. Nothing was off-limits or taboo.”

It was, admittedly, a different approach from that taken by an artist like Mariette Pathy Allen, whose camera was equally intimate but also very humanizing. She spent more than 40 years photographing transgender individuals going about their daily routines, personalizing their struggles for equality and raising consciousness about gender-nonconforming issues. These groundbreaking color images, recently celebrated in a solo show, “Transformations,” at ClampArt, feel as fresh as ever.

Identity Politics, the Culture Wars and the AIDS Crisis

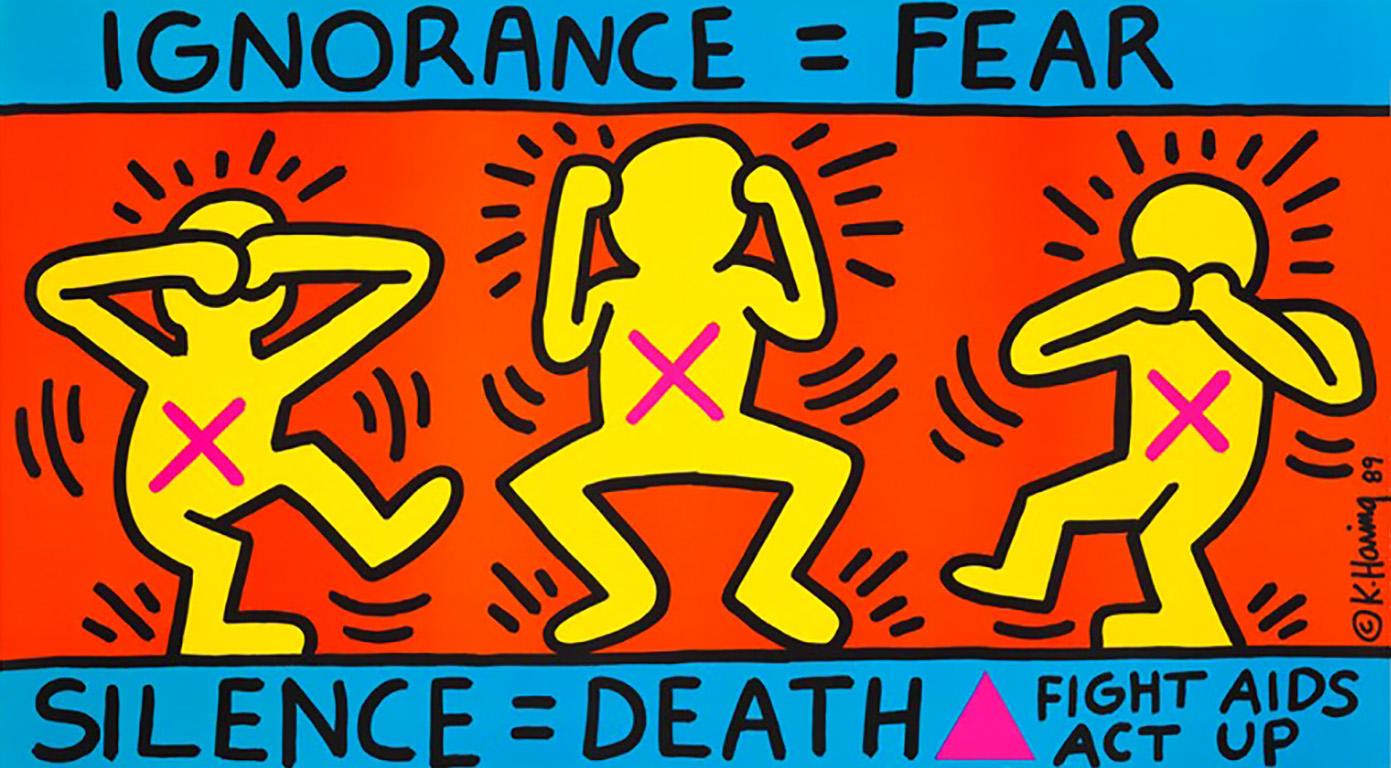

In the reactionary 1980s, as conservatism spread and the religious right stepped up its attacks on anything — including homosexuality — deemed threatening to traditional American family values, art took a more overtly political turn. And as the AIDS epidemic spread and Ronald Regan’s administration failed to react (or even publicly say the word AIDS until 1985), artists like Keith Haring and Donald Moffett mobilized to take direct action. “Visual art can impact things in a different way and sometimes a more powerful way, and we saw that in response to the AIDS crisis,” Clamp says.

Moffet, who would become a founding member of the AIDS activist collective Gran Fury, designed one of the most poignant and potent works capturing the era’s zeitgeist: the offset lithograph He Kills Me (1987), which shows an orange and black target next to a headshot of a smirking Reagan with the title text printed below. It was plastered across buildings in New York City.

While agitprop had a job to do and did it well, some of the most compelling queer art to emerge at the time was exceptionally poetic. “Political art is important, but other types of artwork have also been necessary,” says Nelson Santos, president of the board of the nonprofit Queer|Art and former longtime executive director of Visual Aids. “At the height of the ongoing AIDS crisis, there was art being made that was as personal as it was political, and it was very impactful — work by such artists as Hugh Steers or Eric Rhein, who created personal memorials to friends who were lost to HIV/AIDS.”

Steers painted Hopper-esque scenes that summon isolation and mortality, while Rhein has been working since 1996 on a series of memorial “portraits” — each in the form of a wire leaf — of friends and acquaintances lost to complications from AIDS. There are now more than 250.

“In the nineties, we see more overt homosexual content, but it becomes much more conceptual. And everything is sort of broadening, and there are more possibilities for gay artists,” says Clamp.

Robert Gober, for example, succinctly and lyrically addressed themes of alienation, domesticity, family, sexuality and religion in sculptures and installations that reference the body and the queer spaces it occupies. One such work is Untitled Closet (1989), consisting of an empty closet — a reference, of course, to being closeted — installed in the wall of a gallery. “At first, you didn’t really see that it was in the show,” says Weinberg, who included Gober’s piece in “Art after Stonewall: 1969–89. “You had to realize it was there, which is what the whole piece is about.”

The rise of identity politics — the questioning of the ways race, gender, sexuality, class and other identifying characteristics are used to marginalize and repress groups of people — ushered in a wave of cultural criticism, often expressed through autobiographical work. Some of the most quietly powerful examples, queer or not, came from the Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who used the aesthetics and forms of minimalism and conceptualism to address the loss and longing wrought by AIDS.

Among the numerous abstract portraits he created of his partner, Ross Laycock, who died from complications of AIDS in 1991, is “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A) (1991), which consists of thousands of wrapped candies piled in the corner of a museum gallery and weighing exactly 175 pounds — Ross’s weight when he was healthy. Visitors were invited to take the candies, and as the pile diminished, the waning form echoed the physical deterioration and vanishing of Ross’s body. (Gonzalez-Torres died from complications of AIDS in 1996.)

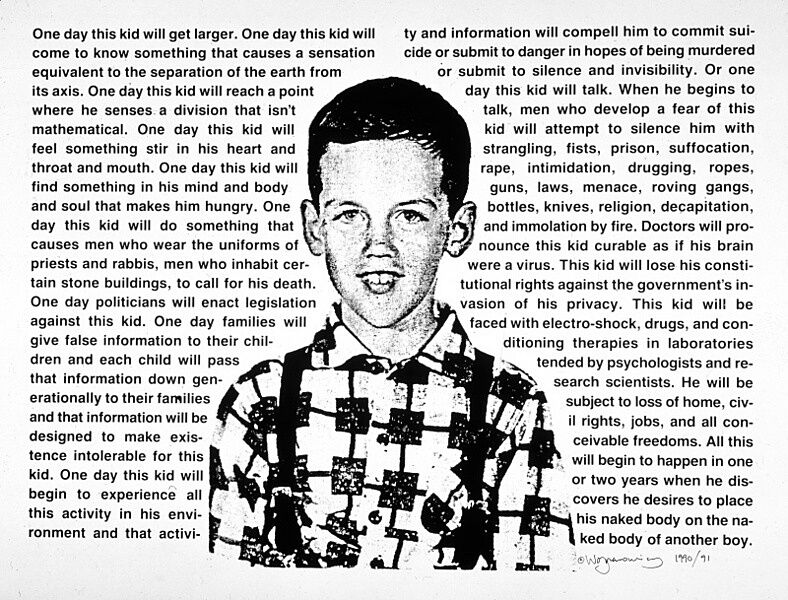

The use of text in art allowed for a forceful directness in the hands of such artists as David Wojnarowicz, who took aim at the brutality of homophobia and the injustice of the AIDS crisis in highly personal yet universal works spanning many mediums.

In One Day This Kid (1990–91), running text surrounds a photo of the artist when he was an adolescent, describing the dark trajectory of a queer boy’s life. As one portion reads, “This kid will lose his constitutional rights against the government’s invasion of his privacy. This kid will be faced with electroshock, drugs, and conditioning therapies in laboratories tended by psychologists and research scientists. He will be subject to loss of home, civil rights, jobs, and all conceivable freedoms.”

Zoe Leonard, an outspoken AIDS activist and ongoing voice of queer feminism (and close friend of Wojnarowicz before he died from AIDS-related complications, in 1992), expressed the sense of urgency to empower the chronically marginalized in her extraordinary 1992 text piece I want a president, which begins: “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with aids for president and a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want someone who grew up in a place where the earth is so saturated with toxic waste that they didn’t have a choice about getting leukemia.”

Photography, with its directness and documentary nature, remained a vital tool for queer artists in the 1990s to explore identity through self-portraiture. Catherine Opie and Laura Aguilar, for instance, both created unflinching images of themselves defying popular idealizations of femininity. For Aguilar, being a working-class Chicana woman added another layer of complexity to her experience as a lesbian.

Black gay artist Glenn Ligon, meanwhile, famously homed in on the intersection of race and sexuality in his celebrated critique of Robert Mapplethorpe’s 1986 Black Book, which featured photographs of idealized black male nudes. For his Notes on the Margin of the “Black Book,” presented in the 1993 Whitney Biennial, Ligon combined Mapplethorpe’s photos with quotes by notable writers, such as Zora Neale Hurston’s “How it feels to be colored me” and Frantz Fanon’s “One is no longer aware of the negro, but only of a penis: the Negro is eclipsed. He is turned into a penis. He is a penis.”

Expanding the Field Today

As cultural institutions and private galleries have recognized the growing need to shine the light on the margins of artistic production, a more diverse group of queer artists exploring identity has entered the fold. “While ‘out’ gay white men, and to a lesser degree white lesbian women, began to receive critical attention from the art world in the nineteen eighties and nineties, it has not been until recently that things have opened up to include more queer artists of color and more trans voices in the visual arts and beyond,” Santos says. “And we still have a long way to go.”

Among the queer artists of color who have landed on the contemporary art map in recent years are painter Kehinde Wiley, who reexamines Black male stereotypes through portraiture, and Mickalene Thomas, whose photographs and paintings reclaim narratives about Black femininity and sexuality. Cuban-American artist Anthony Goicolea stages sometimes-unsettling photographs incorporating multiple images of himself. The South African artist Zanele Muholi, who has been making stunning portraits of South Africa’s Black LGBTQ communities since 2000, considers their art a matter of political urgency, drawing attention to the rampant intolerance and violence toward non-heteronormative behavior in South Africa.

The intersection of race and sex has yielded some especially creative work, rich in cultural references and unexpected overlaps. In her drawing-based practice, the Brooklyn-born Indian-American Chitra Ganesh considers how perceptions of submissiveness, femininity and sexuality have been passed down through coded narratives across the world and across history, from mythology and fairytales to the mass media.

Jeffrey Gibson, who is of Choctaw and Cherokee descent, merges references to his indigenous origins, like geometric forms and heavily beaded garments made in his studio, with pop cultural themes, like ’90s rave culture, to evoke the theatricality of camp, which has long been associated with queerness.

Figurative painting has emerged as a particularly vital form of queer representation. Among the artists who have made especially eloquent use of the brush in exploring the intersection of race and sexuality are David Antonio Cruz, Christina Quarles and Salman Toor. Pakistani-born, New York–based Toor, whose breakout show at the Whitney this past winter and spring was highly acclaimed, paints atmospheric scenes of fashionable young brown men around dinner tables, in living rooms and at bars that seem to portray the contemporary queer social scene through the lens of Van Gogh.

We’ve also seen gender fluidity and ambiguity become more visible in the work of queer artists. Multimedia artist Tuesday Smillie digs into the history of trans-feminist activism and gender-fluidity in literature, while Lissa Rivera photographs her trans partner, and abstract painter Zoe Walsh uses digital processes to gradually transform hyper-masculine images appropriated from gay porn into genderless ones.

The couple Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst documented their relationship over six years, from 2008 to 2014, as they were each transitioning to the opposite gender, through photographs of their daily lives.

“It was a landmark project, not just because it’s trans people taking photos but because they were capturing themselves in their lives doing things that are banal,” says curator and writer Jeanne Vaccaro, who teaches transgender studies at USC and is a postdoctoral fellow at the ONE Archives Foundation there. “Trans people have long been made the subject of the camera as a naked body, as a form of scientific evidence of ‘gender non-normative bodies,’ so taking these kinds of photos of yourself in your house, hanging out and obscured by shadow and light, is really important.”