February 17, 2019A new book by Adele Cygelman explores the work of interior designer Arthur Elrod, whose practice, focused largely on Palm Springs and the surrounding area, helped create the Desert Modern style of the mid-20th century. Top: The club room of the Oklahoma City home of Alta and Roy G. Woods featured a sculpted bronze wall by King Zimmerman. Photos by George R. Szanik

Ask Desert Modern buffs to name the genre’s progenitors, and they will reflexively rattle off a list of deservedly famous architects: William F. Cody, Albert Frey, John Lautner, Richard Neutra, Donald Wexler, E. Stewart Williams, Paul Revere Williams. Mention decorator Arthur Elrod, however, and you’ll likely get a blank stare, even from the most worshipful disciples of Palm Springs mid-century design. That is about to change, thanks to a new appraisal by Adele Cygelman, a respected longtime design editor. Cygelman’s book Arthur Elrod: Desert Modern Design was recently published by Gibbs Smith, and interest in it was strong enough to warrant a second printing even before the official February 12 release, in conjunction with Palm Springs’ Modernism Week.

“I did the book mainly because I wanted to pivot the conversation away from mid-century architecture, which is what everyone has focused on for the past twenty years in Palm Springs,” says Cygelman. “I thought it was high time that credit was given to the interior designers of the period. They worked hand in hand, but it’s the architects who are revered because the structures still stand — mostly — and the interiors are long gone.”

Many of Elrod’s interiors were disassembled in the 1980s and ’90s as tastes changed, observes Cygelman, with custom-designed pieces landing in consignment houses and flea markets. Although Elrod’s interiors were well documented in his day by newspapers and design periodicals, after publication, the articles and pictures mostly sat hidden away in archives. Not until the Palm Springs renaissance began, at the end of the 1990s, did interest in the decorator reignite. “Very sophisticated people — fashion and home designer Trina Turk; interior designer Brad Dunning; and Beth and Brent Harris, who bought Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House in the 1990s — knew his name,” says Cygelman, “but there was no way of researching him.”

In the 1970s, Elrod designed the Palm Springs home of art collector Sig Edelstone. Through the glass walls of the living room can be seen an Alexander Liberman sculpture on the pool patio. Photo by Fritz Taggart

Now, there is. Arthur Elrod, lush with archival photography, renderings, advertisements and correspondence, raises the question “How did this incredibly influential talent fall into obscurity?” Elrod’s client roster could hardly have been more impressive. It included just about every Hollywood A-lister of the era: Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, Mary and Jack Benny, Frank and Lucille Capra, Hoagy Carmichael, Claudette Colbert, Walt and Lillian Disney, Moss and Kitty Carlisle Hart, Laurence Harvey, Bob and Dolores Hope. He was the interior designer of choice for all of Palm Springs’ founding families — the Bennetts, Hickses, McManuses and Nichols — and the darling of every captain of industry who kept a vacation home in the fabled desert resort, including the cofounders of Capitol Records and Hyatt Hotels and an heir to the Carnation Evaporated Milk Company fortune.

Born in 1924, the South Carolina native studied textiles at Clemson Agricultural College (now Clemson University), then interior design at Chouinard Art Institute, in Los Angeles. He arrived in Palm Springs in 1947 and worked as junior staff decorator in the home furnishings department of the newly opened Bullock’s department store. His early career was fueled by the postwar building boom and by a growing awareness in the desert community of modernism, sparked by the work of Schindler, Frey, Neutra and Frank Lloyd Wright. Elrod’s interiors of this period display a mostly French Provincial aesthetic with some sleeker modern furnishings mixed in.

Elrod redesigned the interiors of Richard Neutra’s 1946 Palm Spring Kaufmann House — made famous by Slim Aarons’s photographs — after New Yorkers Joseph and Nelda Linsk bought it, for $150,000, in 1963. The home, which had been empty for years, was in terrible shape. Elrod created a scheme that Nelda (seen above with her dog) describes in the book as “all light, white and yellow—white carpet, off-white upholstery and drapes, textured fabrics, a mix of antiques and modern furniture.” Photo by Julius Shulman, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles

Despite abundant commissions and favorable publicity, Elrod decamped to San Francisco in 1952 for a two-year stint at prominent home design and carpet store W. & J. Sloane. During that time, General Electric engaged him to design an exhibition for the San Francisco Museum of Art to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the invention of Edison’s incandescent bulb. Elrod installed a “penthouse apartment” with terrace in the museum’s galleries that garnered him considerable attention and also marked a turn in his style. Almost all the furnishings were contemporary pieces, by T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings. And, signaling an early innovative impulse, the lighting was subtly integrated into the design — fixtures hidden in valances, a downlight color constellation that changed hues, concealed dimmer-controlled spots and more — rather than added as an afterthought by deploying lamps and chandeliers. “It was the first use of recessed downlights in conjunction with fluorescents,” Cygelman writes.

The groovy late-1960s kitchen of the Woodses’ Oklahoma City home has violet-hued laminate cabinetry bathed in the light cast by a glowing ceiling of fluorescent lamps. Photo by George R. Szanik

At W. & J. Sloane, Elrod met Hal Broderick — who would be his life partner until the 1960s and his business partner until the designer’s death, in 1974 — and Barbara Wills, an assistant manager in the store’s modern furniture department. The three established Arthur Elrod Ltd. and relocated back to Palm Springs in 1954. The firm was instantly successful, and over the years took on more and more designers to meet demand, including, in 1964, William Raiser, a “design heavyweight” who, says Cygelman, shifted the design direction in subtle yet profound ways.

Raiser had worked for 30 years for Raymond Loewy, whom he assisted in designing the interiors of Air Force One for the Kennedys, and had a portfolio thick with commercial and hospitality projects and custom designs. He ushered Elrod’s firm into contract work, assumed control of its custom rug and carpet designs and refined its signature look into something more polished and layered.

Elrod literally created the mid-century Palm Springs interiors aesthetic we take for granted today. His was the first firm to bring national lines like Baker and Widdicomb to the desert. “He poured surfboard resin over fabrics to create countertops,” says Cygelman. “Who else was doing that?” Elrod also pioneered the use of indoor-outdoor fabrics, covered a fireplace wall with green vinyl and made Naugahyde chic. He floated credenzas on wall panels and under-lit sofas and beds with recessed kickbacks so that they appeared to levitate. “We are living now,” Elrod told Architectural Digest in 1972. “Homes should reflect the materials and craftsmanship of today rather than the past.”

The firm had a fearless approach to color as well. “Color is not easy to do,” Los Angeles designer Brad Dunning told Cygelman. “Other decorators of the period were doing similar work, but no one did it better than Elrod — bold colors that were so ballsy, but he pulled it off. . . . He could do those patterns and bright colors on a par with the best Color Field painters . . . but he was doing it in 3-D.”

The living room of Elrod’s own iconic domed, concrete-and-glass ridge-top Palm Springs home — designed by architect John Lautner and completed in 1968 — features a round Edward Fields rug, a Martin Brattrud bench, Pierre Paulin Ribbon chairs and a mobile by Mimi Kornaza. On the pool terrace are blue-upholstered outdoor chairs by Danny Ho Fong. Photo by Leland Y. Lee

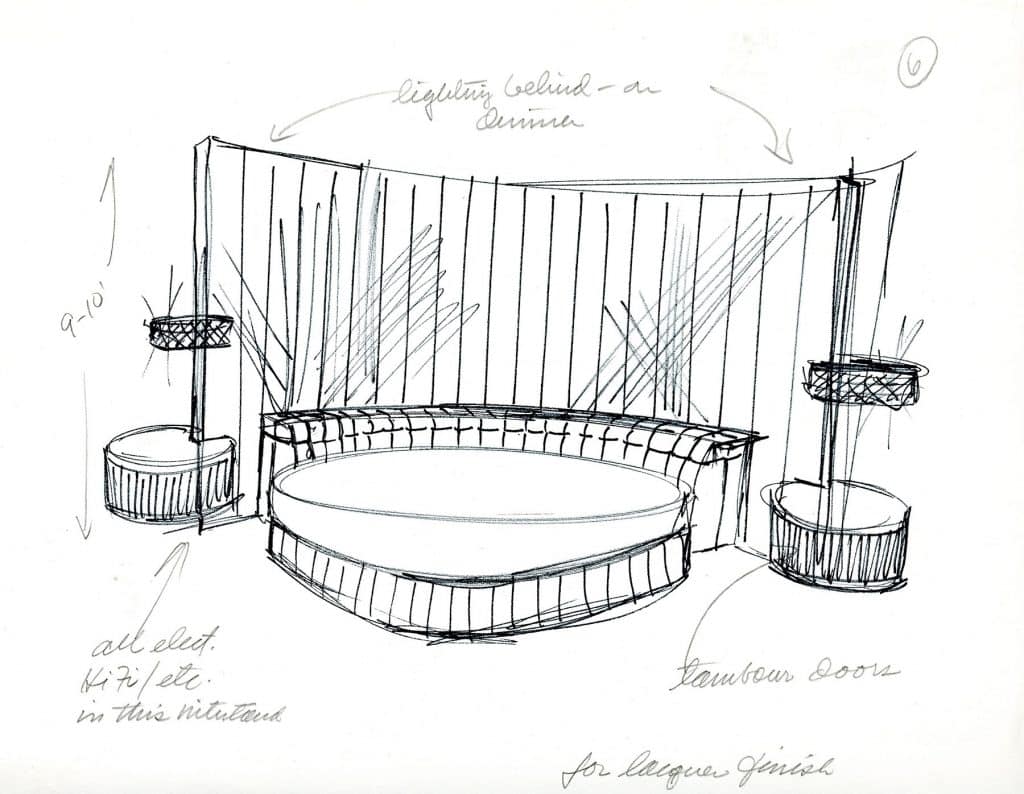

Elrod commissioned rising talents (Karl Springer, John Vesey and Milo Baughman) to create custom work for projects. He also embraced technology, designing speakers into consoles and embedding stereo and lighting controls into furniture. In a time when we can adjust our world from our armchairs on iPads, it’s easy to forget how revolutionary his tech savvy was back then. “It’s taken forty years to catch up to that,” notes Cygelman.

Former AD editor Paige Rense Noland, who splashed many Elrod interiors across the publication’s pages in her early days there, observes in the book that he persuaded clients “to look at their second or third house on a par with their primary residence. He made clients want to spend money on their weekend home.” Unlike most decorators of the day, Elrod often designed clients’ Palm Springs homes before being asked to redo their primary residences in cities across the country, from Honolulu to Chicago to New York.

Cygelman calls his style “smooth and sexy.” No surprise, then, that Elrod’s own home, designed by architect Lautner, landed a role in the James Bond film Diamonds Are Forever as Willard Whyte’s desert abode, where the tycoon sat under house arrest, guarded by martial arts vixens Bambi and Thumper.

Elrod and the Desert Modern architects with whom he collaborated transformed Palm Springs into a design mecca. “Entertaining in the desert is much more formal now,” Elrod told the Desert Sun in 1962. “We are becoming more urbane and cosmopolitan with every passing season. And the décor of our homes reflects these trends.”

For one of Elrod’s previous Palm Springs residences, purchased in 1958 in the town’s Movie Colony neighborhood, Cygelman writes, he selected “a rug woven in raised multicolored patterns, an abstract painting, white furniture, and floor-to-ceiling shutters” to create “a contemporary beat.” Photo courtesy Harold C. Broderick/Arthur Elrod Associates, Inc. Collection, Palm Springs Art Museum

So, what happened — why did he all but disappear? “Definitely, being regional hurt him,” says Cygelman. “Even though lots of projects were published in AD, at first it was a very regional magazine, and I don’t think anyone was paying attention to what was happening in Palm Springs at the time.” Elrod and Raiser also died young (49 and 58, respectively), when their car was broadsided by a drunken teen’s pickup truck. “He didn’t really get national coverage until the nineteen seventies,” Cygelman explains, “and he died just as AD was becoming a national magazine, right when he was getting huge commissions with budgets in seven figures.”

The firm’s partners kept Arthur Elrod Ltd. going long enough to finish the projects Elrod and Raiser had begun. But without its two leading visionaries, the “Elrod look” morphed into something else, and commissions dwindled until Broderick finally closed the company in 1996 and retired to Sonoma. Arthur Elrod: Desert Modern Design persuasively argues that had Elrod not been killed, the odds are excellent that he would have enjoyed iconic status during his lifetime and not required the rediscovery Cygelman’s book now accomplishes.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore