November 20, 2017Ashley Hicks, pictured with Mia, one of his Italian greyhounds, has published David Hicks Scrapbooks, a compilation of his father’s career-spanning media clippings, photos and memorabilia (portrait by Arnaud Pyvka). Top: Hicks and his wife, Katalina, share his late father’s apartment in London’s tony Albany (photo courtesy of Ashley Hicks).

Books, linens, sculptures, fabrics, tables, chairs, mirrors, lighting, wallpaper, rugs, houses, swimwear. There might be a design area toward which Ashley Hicks has not yet turned his hand, but it’s surely just a matter of time. “I like it all,” Hicks says cheerfully. “I even like writing, although I’m probably dreadful at it.”

Hicks, the son of the very famous designer David Hicks, has honed the British art of self-deprecation. But talking to him in his small and expertly formed apartment (known as a “set”) in London’s storied Albany building, across the road from Fortnum & Mason, it is quite clear that he is a one-man creative powerhouse, with an idiosyncratic and purist eye on everything; from the walls (hung with burlap on which he has painted sepia-toned scenes of Greek muses and river views – “perfectly simple”), to the large totem sculpture made of colored cast resin, to the tiny kitchen whose cupboards are decorated with intersecting lines of brass nails.

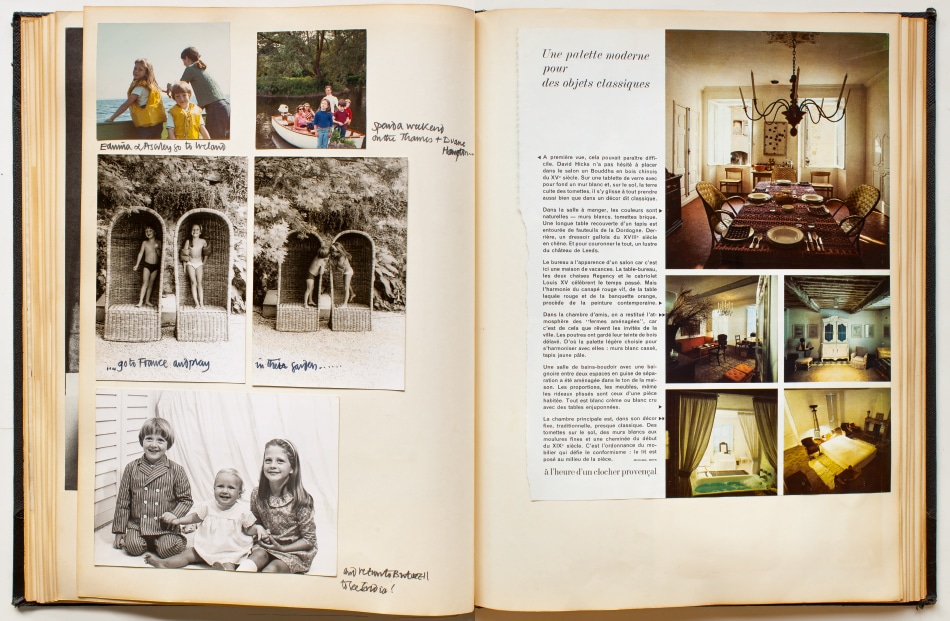

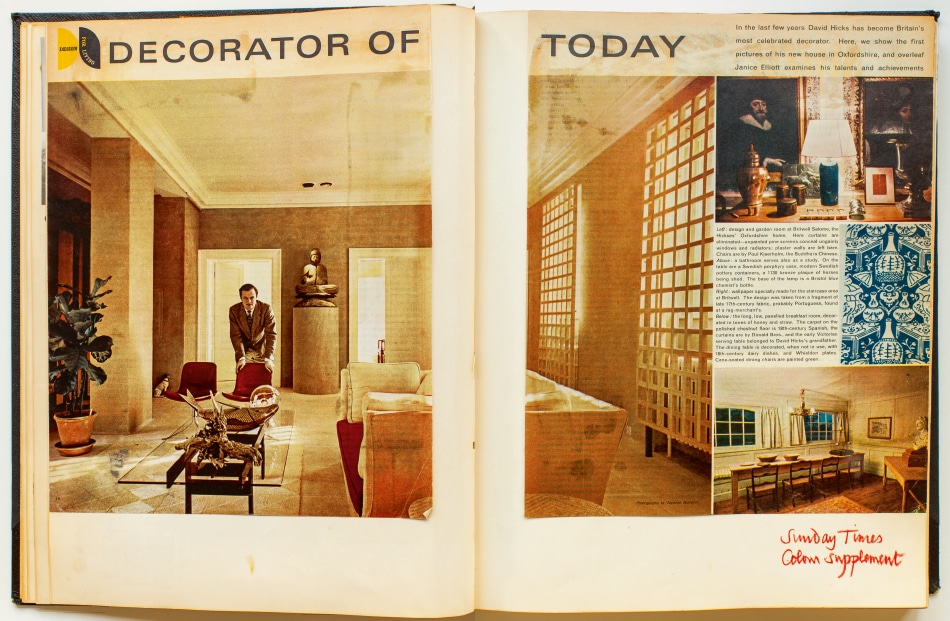

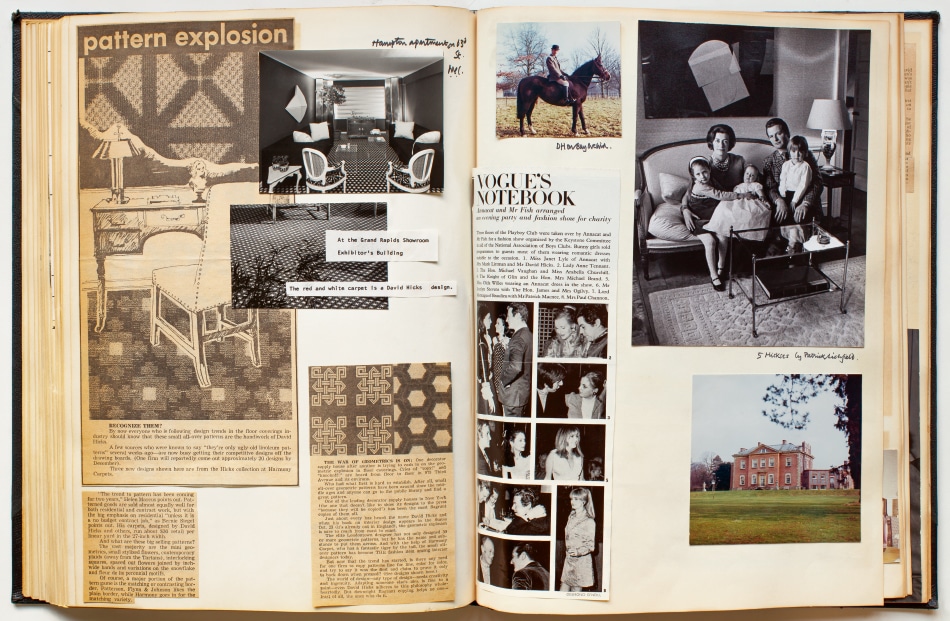

Hicks grew up, the second of three children (his younger sister, India Hicks, is also a designer), in Britwell House, an 18th-century manor in Oxfordshire that served both as a showcase for his father’s work and as a glorious setting for the dinners and parties hosted by his glamorous parents. (Hicks’s mother, Lady Pamela Mountbatten, is related to the British royal family; Prince Philip is his godfather.) “I suppose living there formed my tastes, which incline toward the classical,” he says. “And my father always had me watching him work and looking at his scrapbooks. Every week there were new pages.”

Those pages are the subject of Hicks’s most recent venture, David Hicks Scrapbooks (Vendome), a distillation into one weighty tome of 25 volumes of cuttings, photographs, letters, swatches and memorabilia that David Hicks assembled and preserved until his death, in 1998. In the colorful, eclectic and impeccably composed living room at the Albany (which he shares with his dynamic American-born wife, Katalina), Hicks talked about his early interest in design, his father’s overwhelming personality and his preference for flexibility in his work.

In 1980, Slim Aarons photographed the Hicks family at Savannah, their estate in the Bahamas, including David and Lady Pamela Mountbatten and their children, Ashley, India and Edwina, along with George Mountbatten. Photo by Slim Aarons

Were you always interested in design, or was it just impossible to escape in your house?

I was always interested. I was my father’s only son, which mattered since he had a fairly old-fashioned attitude about women. He thought his daughters would be ladies and marry dukes, whereas I would carry on the work and the heritage. So, all through my childhood, he talked to me about his projects, had me close by, encouraged me to look at his scrapbooks. My own designs as a child were a bit different. At school, instead of working on whatever class I was in, I used to design secret-agent equipment and military hardware, jet engines. I still have a whole file of stuff I did at twelve, and the drawings are rather impressive in their precision. Then, when I became a difficult teenager, I decided to be an artist.

Was that a kind of rebellion?

Absolutely! Also, because my father had wanted to be an artist and had gone to art school. He went all over Italy for a summer painting, had an exhibition, didn’t sell any work and promptly decided to be a decorator instead.

But, of course, I finished art school and thought, “Where will I go with this?” I wasn’t particularly helped by having a celebrated and creative father who was in the newspapers all the time. It made me panic-stricken about selling work, how to go about it. And he probably discouraged me by saying something like, “It’s impossible unless you are Francis Bacon!” And, of course, I wasn’t Francis Bacon.

I probably felt safer in a more academic environment, and I went to study architecture at the Architectural Association, which was a pretty nuts place. I think we had about three days of actual tuition — for the most part, we were treated as if we were already young architects and given ridiculous briefs. I remember that the first one was an underground zoo! But I was hugely enthusiastic for the first couple of years, even though I was slightly trying to escape from the incredibly strong modernist orthodoxy that prevailed. I loved classical architecture, and I spent a lot of time in the library looking at books about it. I found one about ancient Greek furniture, and many years later, I designed a Klismos chair based on that.

A 1967 landscape painting by David Hicks hangs over the headboard in the bedroom of Ashley Hicks’s daughter Ambrosia in the family’s former South Kensington apartment. Ashley designed all the furniture, including the cast-aluminum chaise longue, which is upholstered in his father’s Ambrosia Rose pattern vintage linen. Photo courtesy of Ashley Hicks

Did you practice as an architect?

Yes, for a while. After I qualified, I worked partly with my father, partly with someone else. But I didn’t really like it. I hated being caught between the contractor and the client and being heartily disliked by both! At some point, I found drawings I had made from the Greek furniture book and decided to make a chair. I had a friend in India who had some carpenters, and they made it for me. It was somewhat successful, and after a few years, I had altogether stopped architecture and was making furniture and doing interiors. Then my father died and left his design rights to me — because my sisters were going to marry dukes, if you remember — so I started doing some licensing with American fabric and carpet companies.

How did the interior design work begin? With clients who bought furniture?

No, I am terrible at selling things to people, so I never really offered my own furniture. I can’t really remember how it started. I think just through people I met or knew. But I have never done a huge amount of interior design. I don’t like managing people, and I like to be flexible and move from one kind of project to another. So, I do a lot of different things. I’ve just done the scrapbooks, and now I’m working on a book about the interiors of Buckingham Palace and photographing it myself.

Had you always wanted to do something with your father’s scrapbooks?

No, not particularly. It first came about through Idea Books. They sell my father’s books and are obsessed with him. They kept tagging me on Instagram, and eventually I went to meet them. They have a publishing arm, doing very limited editions mainly with fashion (skateboarding clothes!), and they immediately said, “Let’s do a book.” At first, I thought about my father’s travel photographs, but then I suddenly thought about the scrapbooks. I had already scanned quite a lot of pages, and I thought I had a lot of the material ready.

Of course, when I looked at them again, the quality wasn’t great, and I decided they had to be photographed in daylight. So, it turned into a huge amount of work — photographing every page, then color correcting every single thing. We made a series of four soft books in an edition of two hundred fifty, and it sold out in three days. So, my friend Francesco Venturi, at Vendome Press, said, “Let’s do a hardback one.”

How difficult was it to reduce twenty-five scrapbooks to a single, albeit generous-sized, volume?

Difficult! There were about three thousand pages in the original scrapbooks, and the four-volume edition had six hundred pages. Then this one has around three hundred, so it’s the best of the best. I tried to choose material that hadn’t been published in his books or in the books I’ve done on him. There is wonderful stuff and a lot of variety. He collected absolutely everything written about him, even the negative things, and stuck in invitations, letters he had written, swatches. And photographs — the only bad one ever taken of Jackie Kennedy. There are pictures of us, my mother, a garden party with Shirley MacLaine and Rex Harrison, others of a visit from Princess Grace and Prince Rainier. I didn’t add captions, just an introductory note at the beginning of each section. The pages are exactly as they were in the scrapbooks.

David Hicks, pictured at home, kept scrapbooks documenting his life and career, filling 25 volumes. Photo by Victor Watts

Did you organize the book chronologically?

Yes, but some sections cover three years while the last covers twenty-two years. I’ve concentrated on the first twenty years of my father’s work, partly because the 1960s and ’70s look fabulous to us today but also because I think the work really is stronger and those pages are visually much richer. My father was an early peaker. There was an extraordinary outburst of creativity and brilliance from when he married my mum, in 1960, until 1979, when my grandfather was killed by an IRA bomb. I think afterwards things sort of fell apart.

Which are your favorite pages in the book?

There is a page from 1964 with photographs of a visit to Haile Selassie in Ethiopia that shows [the emperor’s] leopard chained up outside the palace and my mother in jodhpurs and gin and tonics served in silver beakers. It’s great!

I also love a spread of invitations he shows for the opening of David Hicks Paris in 1973. Pride of place is given to a note from Princess Grace saying they are not able to come.

And then there is this one from March 1979: “David Hicks Says Goodbye to His Dream House.” His business had gone bust, and they were leaving the house and selling everything, but here he is posing in his cloak and spending hours composing the photograph for the Sotheby’s catalogue. Even though it was a bit of a humiliation, he turned it into an exciting new opportunity. “You can design your own room in our new house,” he told me. “Or I can do it.” I said, “No, I’ll do it.” And I did, entirely in black and white, probably because my father was always saying, “No one can do color like me.”

Was it difficult to grow up with David Hicks as your father?

I’m not sure. He was a strong, slightly confusing personality. Tremendously loving and sweet but also a raging narcissist, which isn’t the easiest thing. There was never a dull moment, but it wasn’t confidence building for a son. The designer Nicky Haslam used to tell me how my father would go on and on singing my praises, but of course, he never said any of those things to me.

Or Support Your Local Bookstore