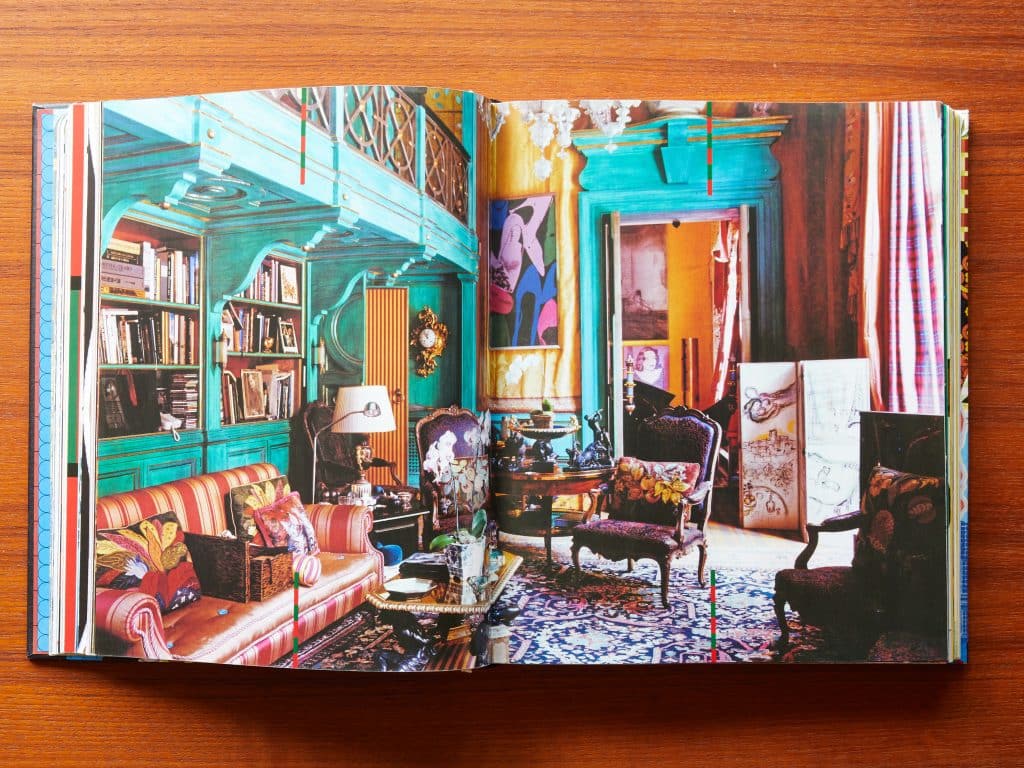

December 13, 2020It’s Joe Holtzman’s world. I just live in it. Do you? As an aspiring architect in the 1990s, I occasionally flicked through Holtzman’s Nest, the late, lamented shelter quarterly that the flaneur-cum-decorator published from 1997 to 2004 out of a rental apartment down the hall from his home on New York’s Upper East Side. Something about its pages — jammed with a heady, unlikely mix of giltwood chandeliers, Eero Saarinen pedestal chairs and stainless-steel prison toilets — must have rubbed off. And I’m not even talking about stray velvet fibers from the famous cover of his second issue, which sported a flocked paper commissioned from German conceptual artist Rosemarie Trockel.

Today, my East Village living room has a BDDW blanket-stripe chaise, Josef Ramée floral-swag wallpaper designed around 1815 and a framed Roy Lichtenstein film still from 1971. Such mad eclecticism is not exactly the manner in which I was raised. But it came from somewhere.

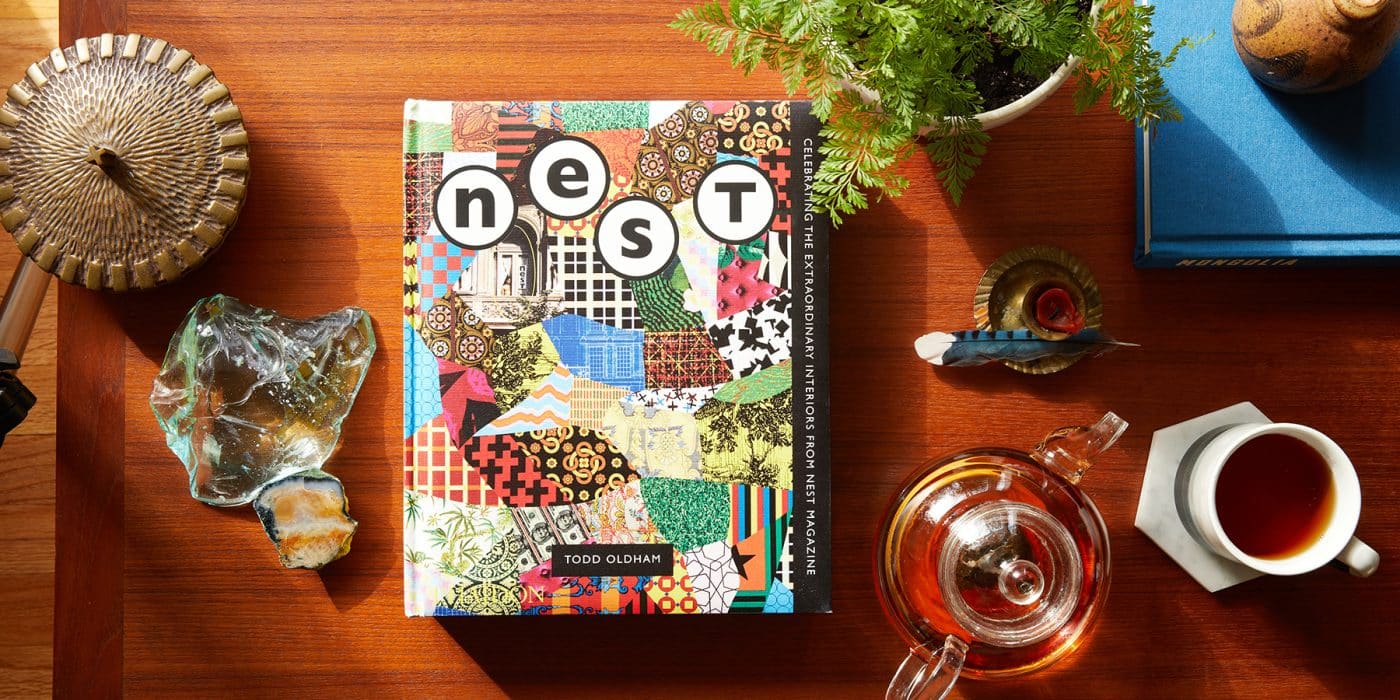

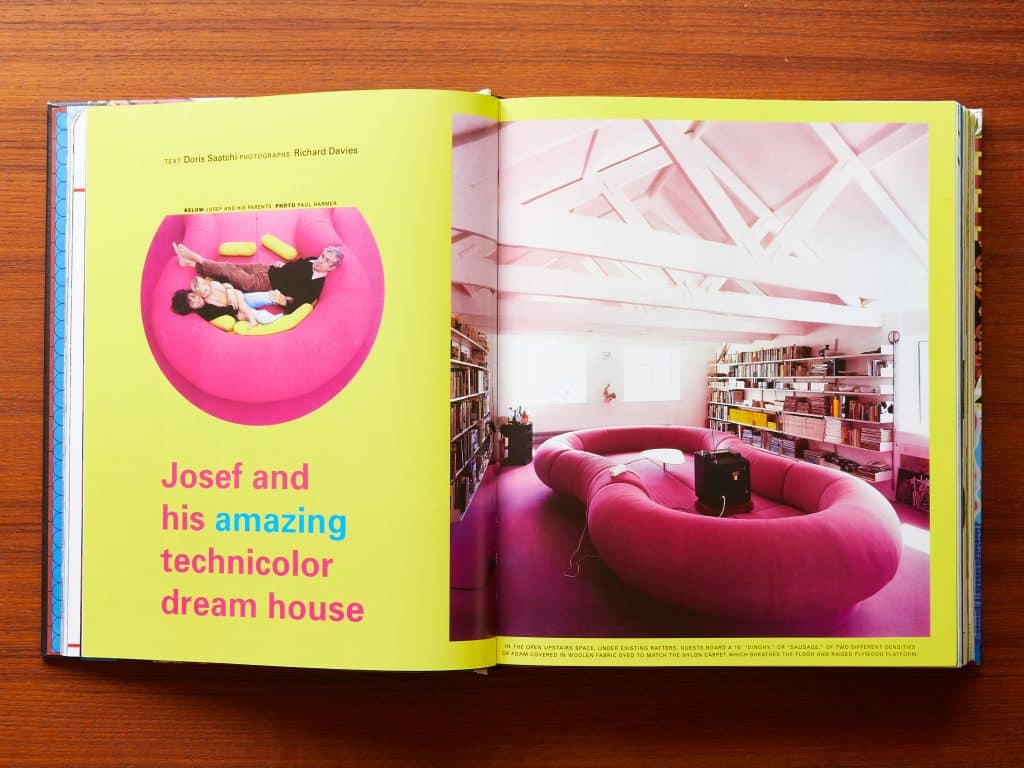

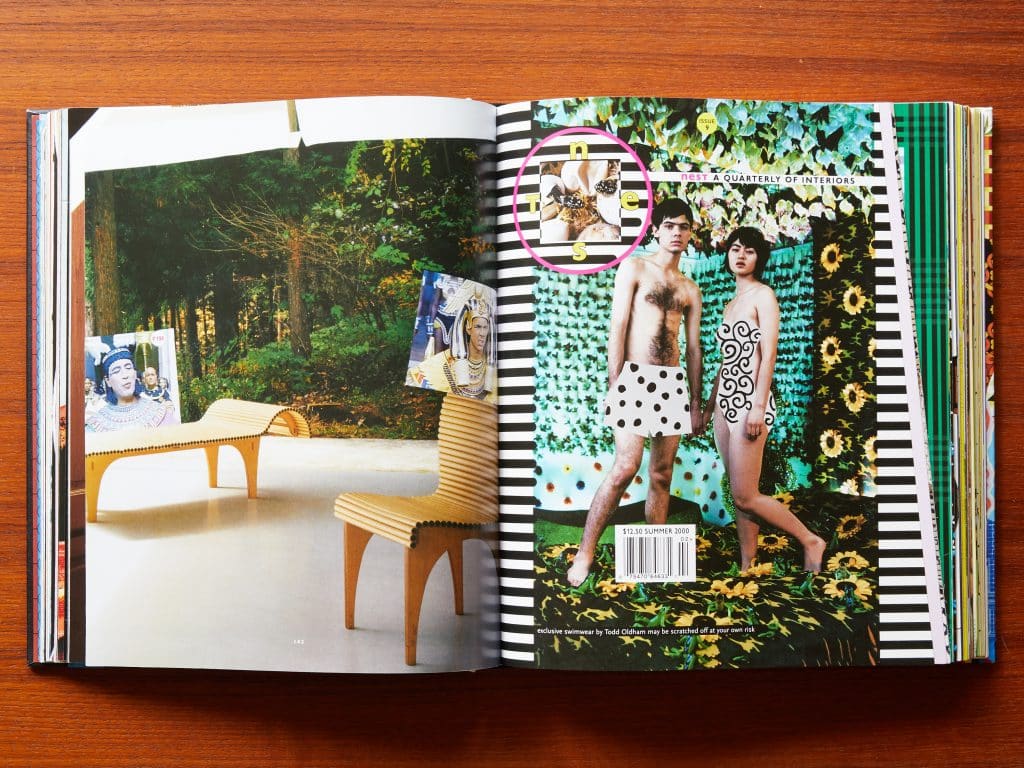

Leafing through the exhaustive new 524-page hardback The Best of Nest (Phaidon), I found the source. Compiled by Todd Oldham — a Nest contributor, fashion designer and former host of MTV’s House of Style who has subsequently turned to consumer products and book packaging — the book reminded me that it was this magazine that provided the fabulous urtexts for my alarmingly demented decorating, and that of so many others, too.

Oldham shot more than 20 features for Holtzman. For the book, he grabs representative spreads and stories, both his own and others’, from each of Nest’s 26 issues, reprinting them in the order in which they originally appeared. (The book project occurred to Oldham, and got Holtzman’s approval, after another idea — the release of boxed sets of Nest back issues — went up in smoke, literally, in a warehouse fire.)

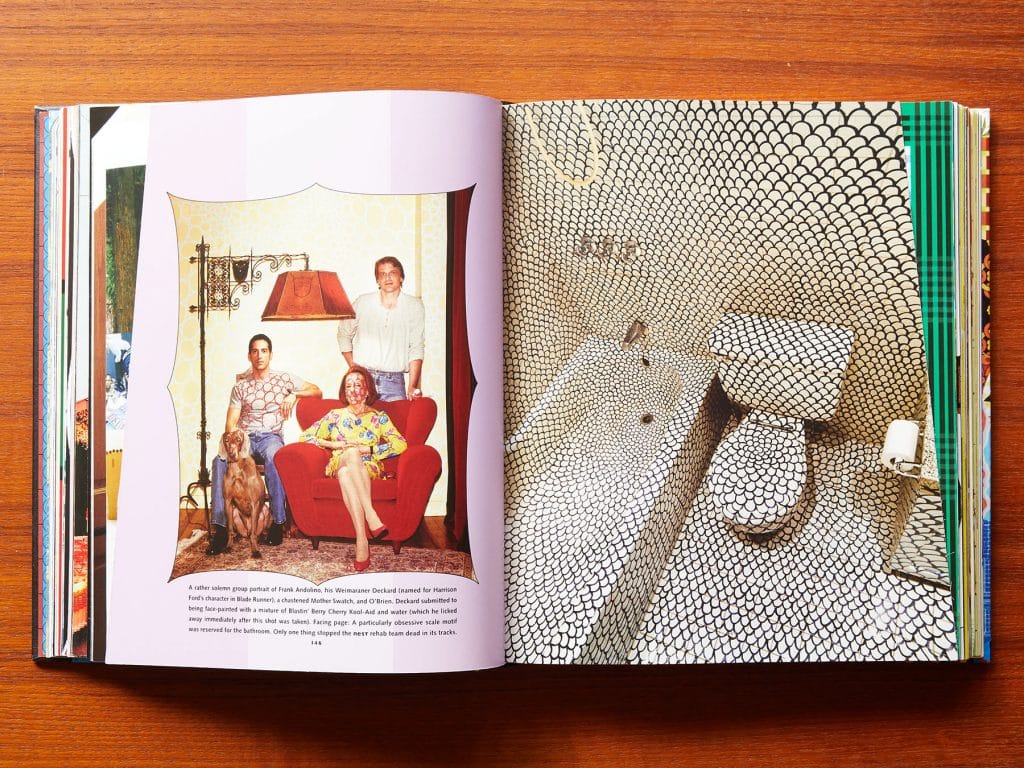

According to Oldham, Holtzman — who served both as Nest’s editor in chief and its art director — was both a generous boss and an extremely unlikely impresario. “Joe is deeply unusual,” he says, “just a square peg.”

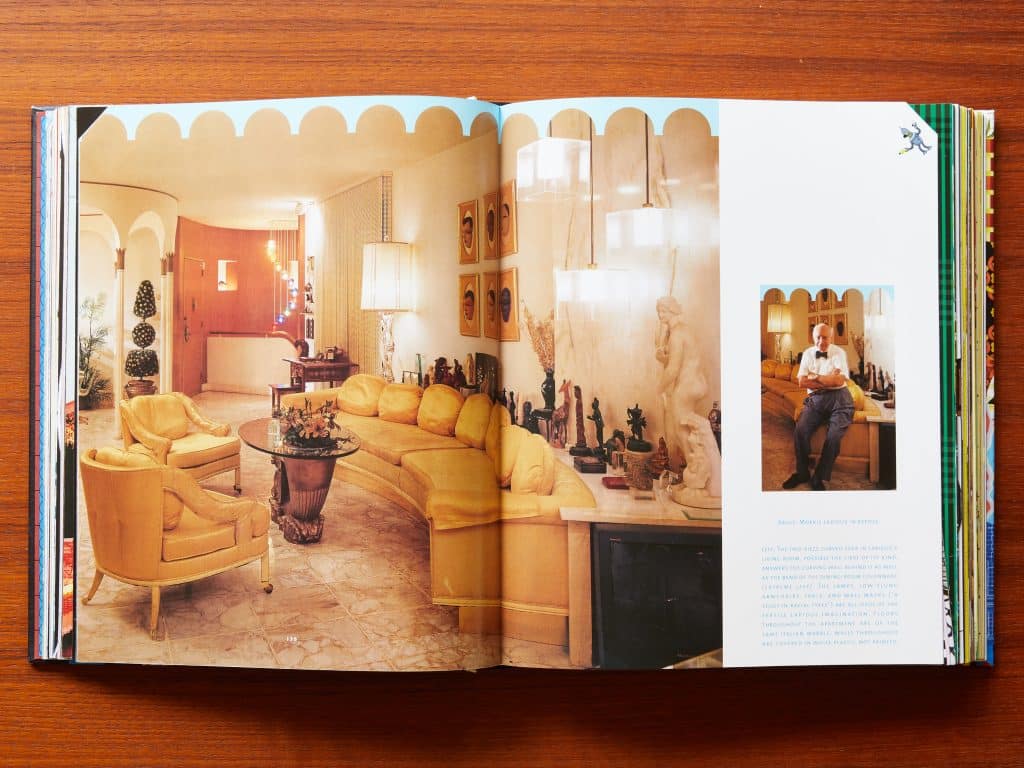

Holtzman grew up as a reclusive rich kid in Maryland, moving to Manhattan in the 1990s from the spoiled seclusion of his relatively provincial youth. As an arriviste, he wasn’t burdened by the conventions of New York’s publishing industry. That freed him, and his magazine, to profile a kid from the IKEA decorating department with the same interest and curiosity that he bestowed on such design doyens as Mario Buatta and Andrée Putman.

Oldham writes admiringly in the book that Nest “felt like a magazine made by someone who had never seen a magazine before.”

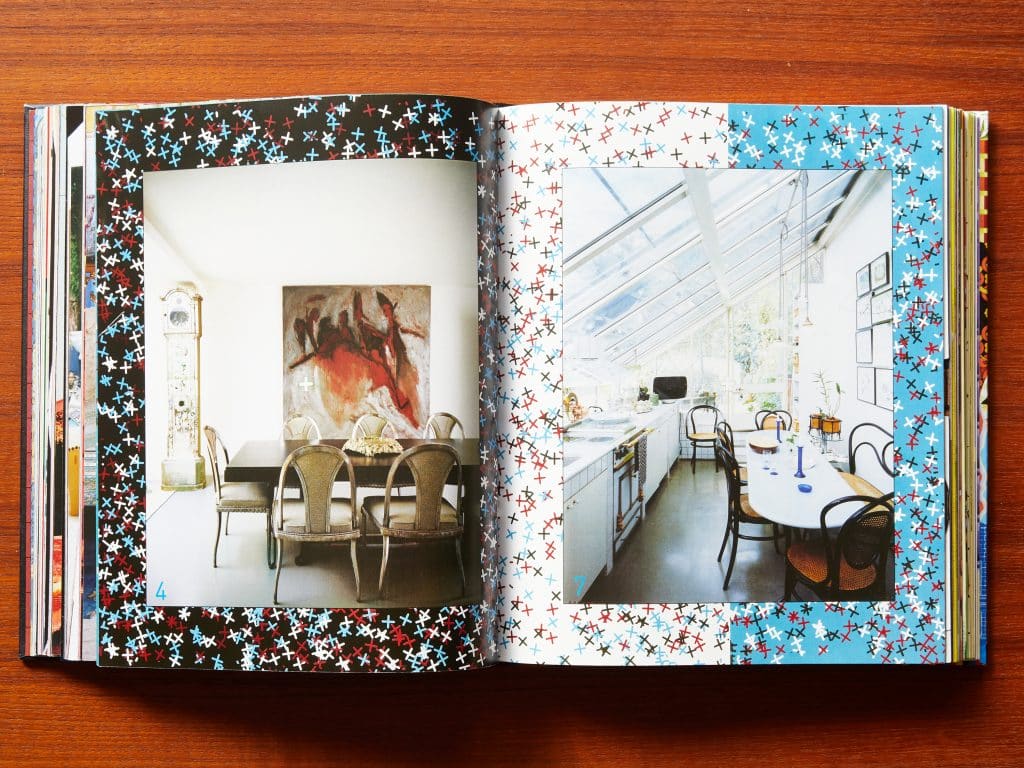

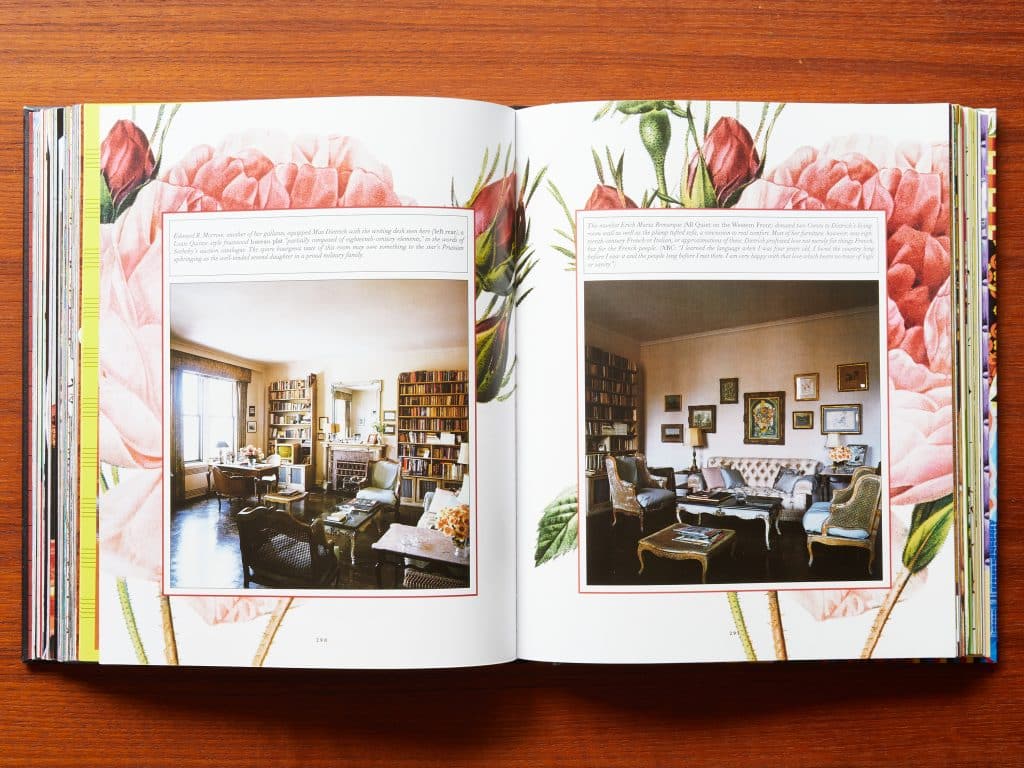

Decades before Victorian granny florals reappeared on walls like mine, Nest deployed them incongruously on its pages, as a sort of bizarro graphic frame for assorted photos of Bauhaus interiors. In 2002’s fall issue, enlarged botanical drawings of cabbage roses sit beneath photos of Marlene Dietrich’s grandmotherly Manhattan apartment on Park Avenue.

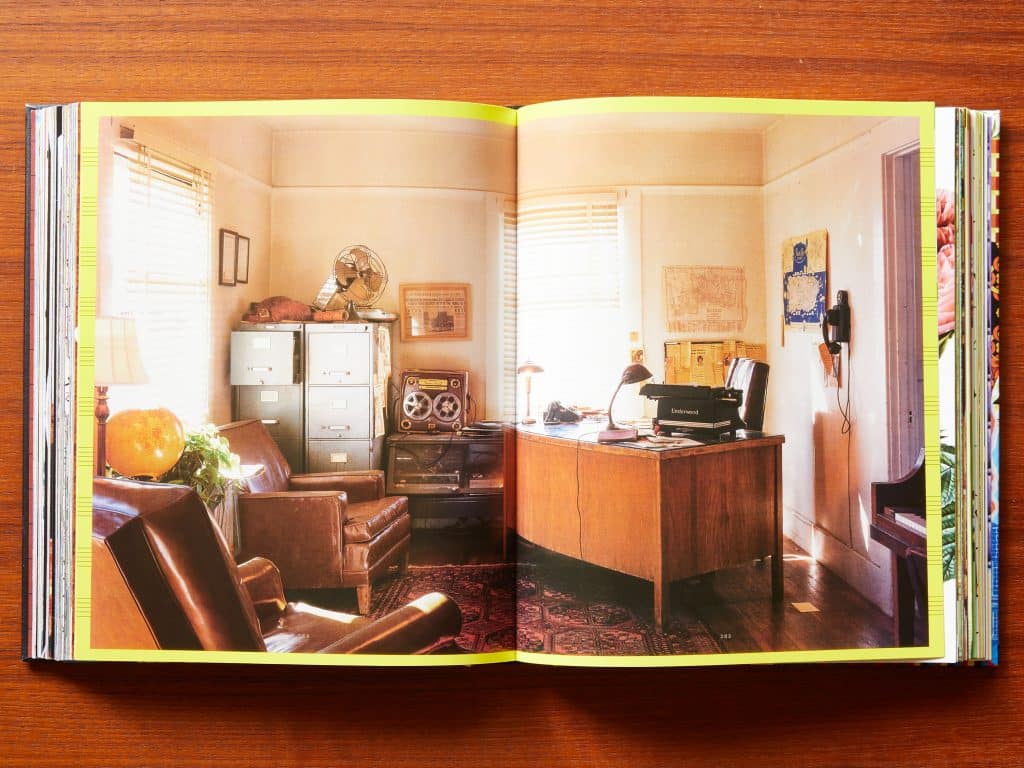

Holtzman clearly had no templates for Nest stories, and certainly no rules. His subjects ranged from the overtly macabre to the merely eccentric in stories showcasing palaces, pissoirs and more than a few nude models — posed in, for instance, a plastic Garden of Eden. With his first editor’s letter, Holtzman asserted that “our houses have private parts. Nest is no waist-up publication.”

In his present-day running commentary, included in the book opposite reprints of his editor’s letters, Holtzman asserts that he didn’t care who his audience was so long as it wanted to see “the full range of humanity’s domestic doings, under the sign of the decorator.”

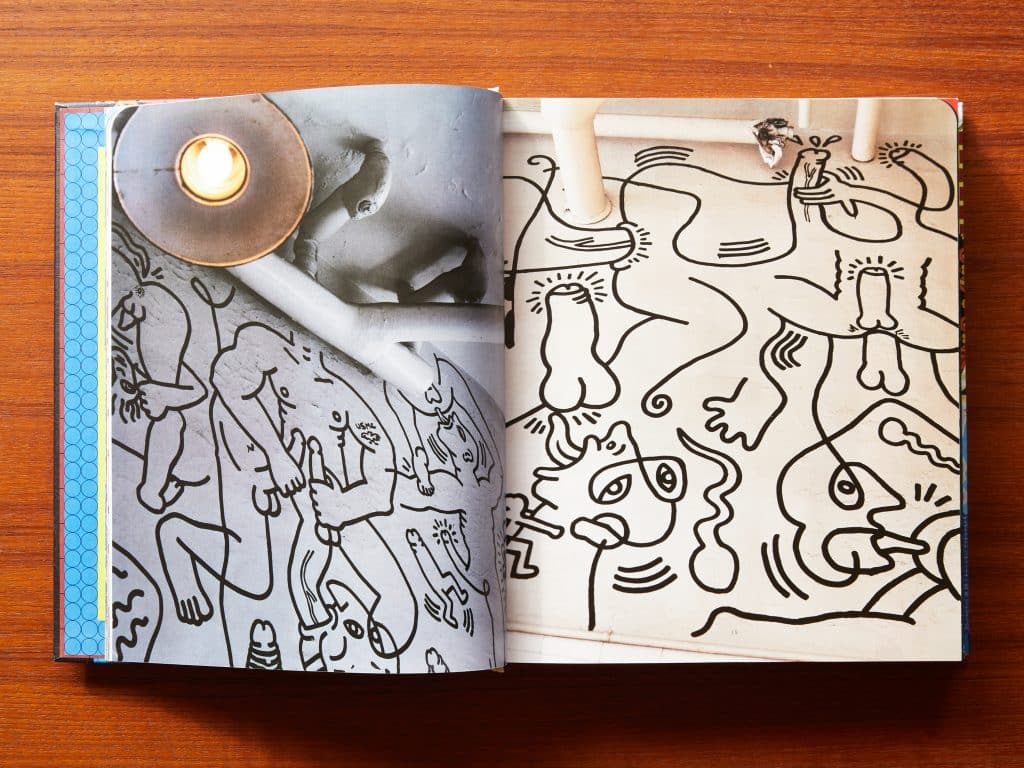

As it turned out, there was a surprisingly ample audience for just that sort of thing. Holtzman’s premiere issue — which included a story titled “Haring’s Guernica” about an X-rated 1989 Keith Haring cartoon mural in a bathroom at Manhattan’s Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center — needed a second printing.

“People were very much ready to be shaken up,” says veteran design journalist and Nest contributor Mitchell Owens, explaining the quarterly’s unexpectedly broad appeal. Editors at shelter publications expressed jealous admiration “whether it was to their taste or not.”

Nest showed “the underbelly of design and sometimes challenged common sense,” continues Owens. Now the decorative arts editor of Architectural Digest, he wrote for Holtzman on the side while working for Traditional Home and as a reporter for the New York Times. “I found it very freeing,” he says of his Nest work, “and it was great, great fun.”

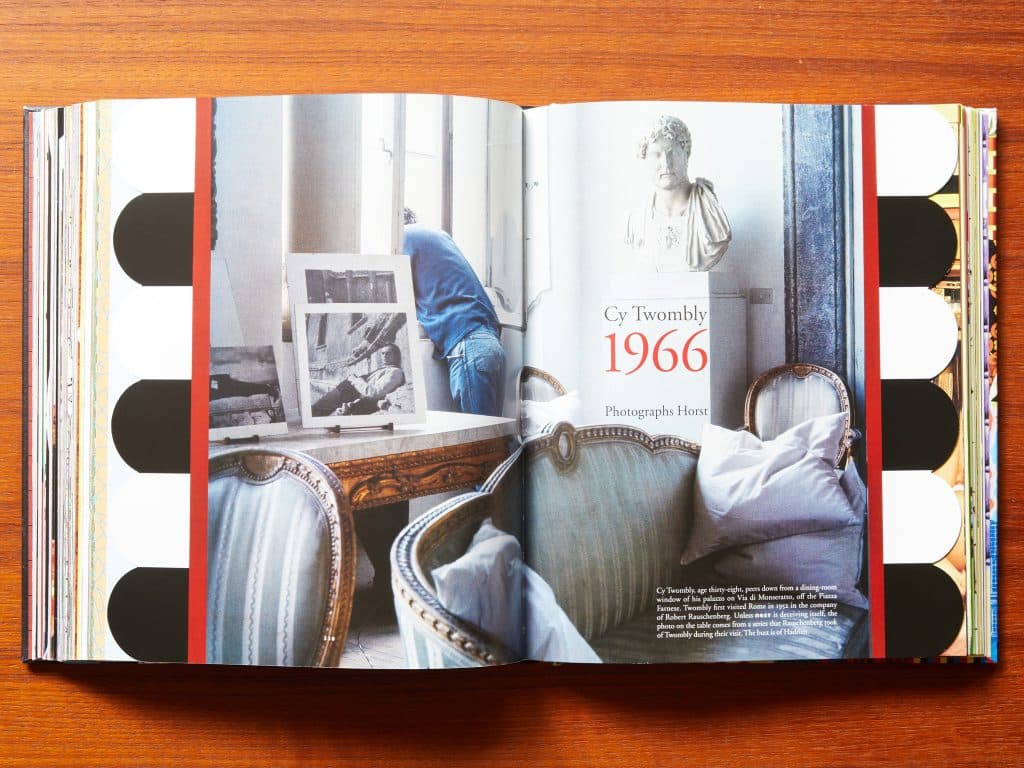

Holtzman, the book makes abundantly clear, let his contributors enjoy themselves, liberating them to jump down the most rarefied rabbit holes.

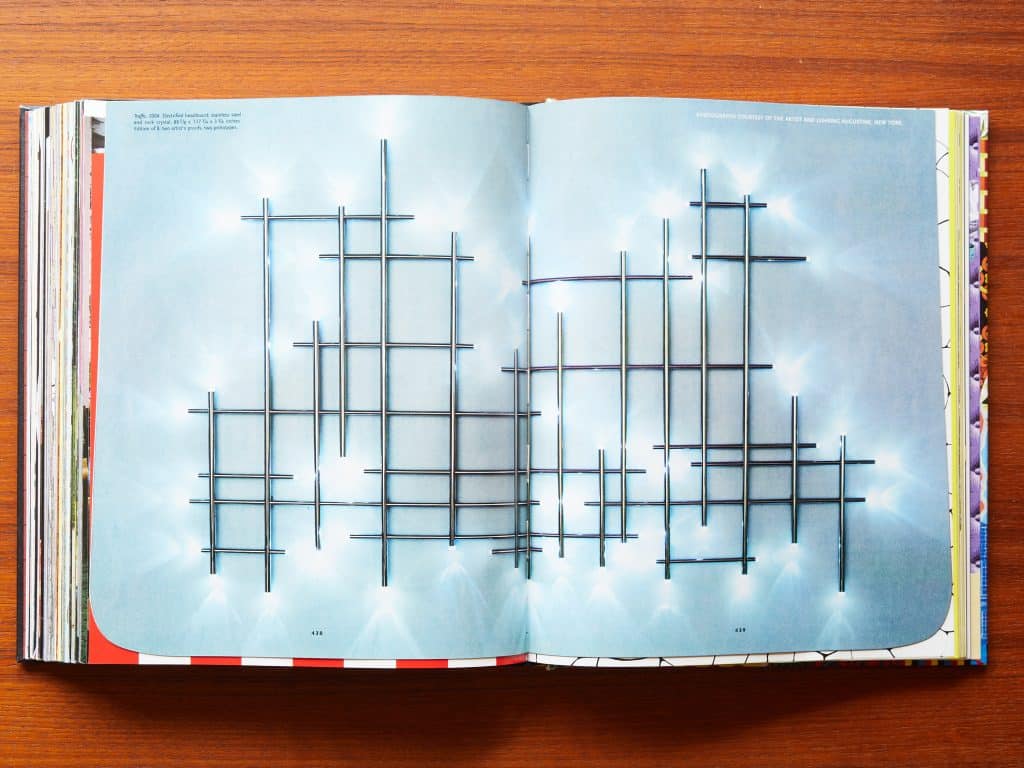

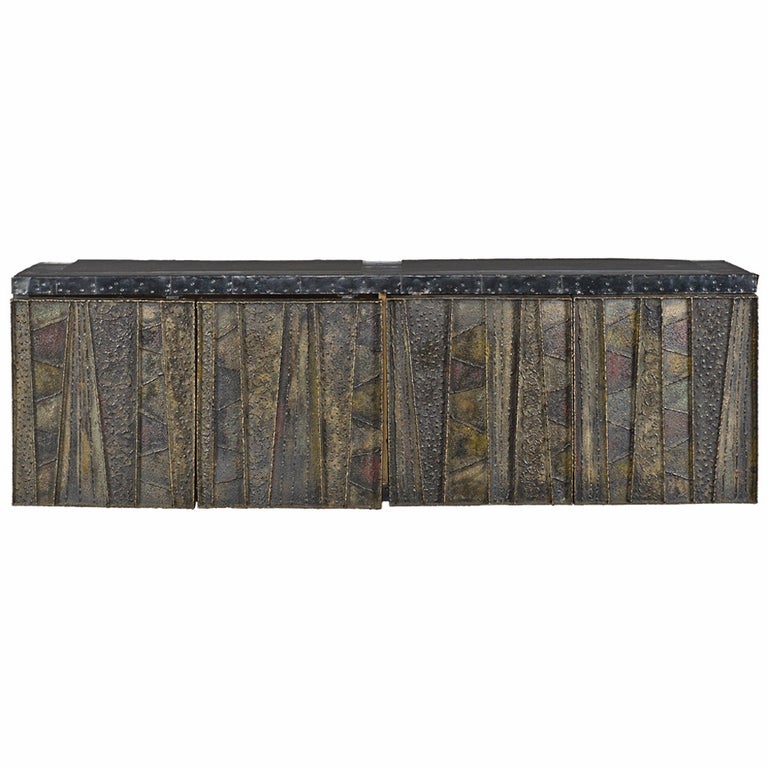

Art furniture was barely a fledgling market in 2003, when the magazine showcased the blobby ceramic triptych mirror by Mattia Bonetti that Philip Johnson and his partner, David Whitney, hung over the fireplace of their ranch in Big Sur, California. Holtzman featured Bonetti again and again over the years, at one point devoting an entire portfolio to his furniture and lighting.

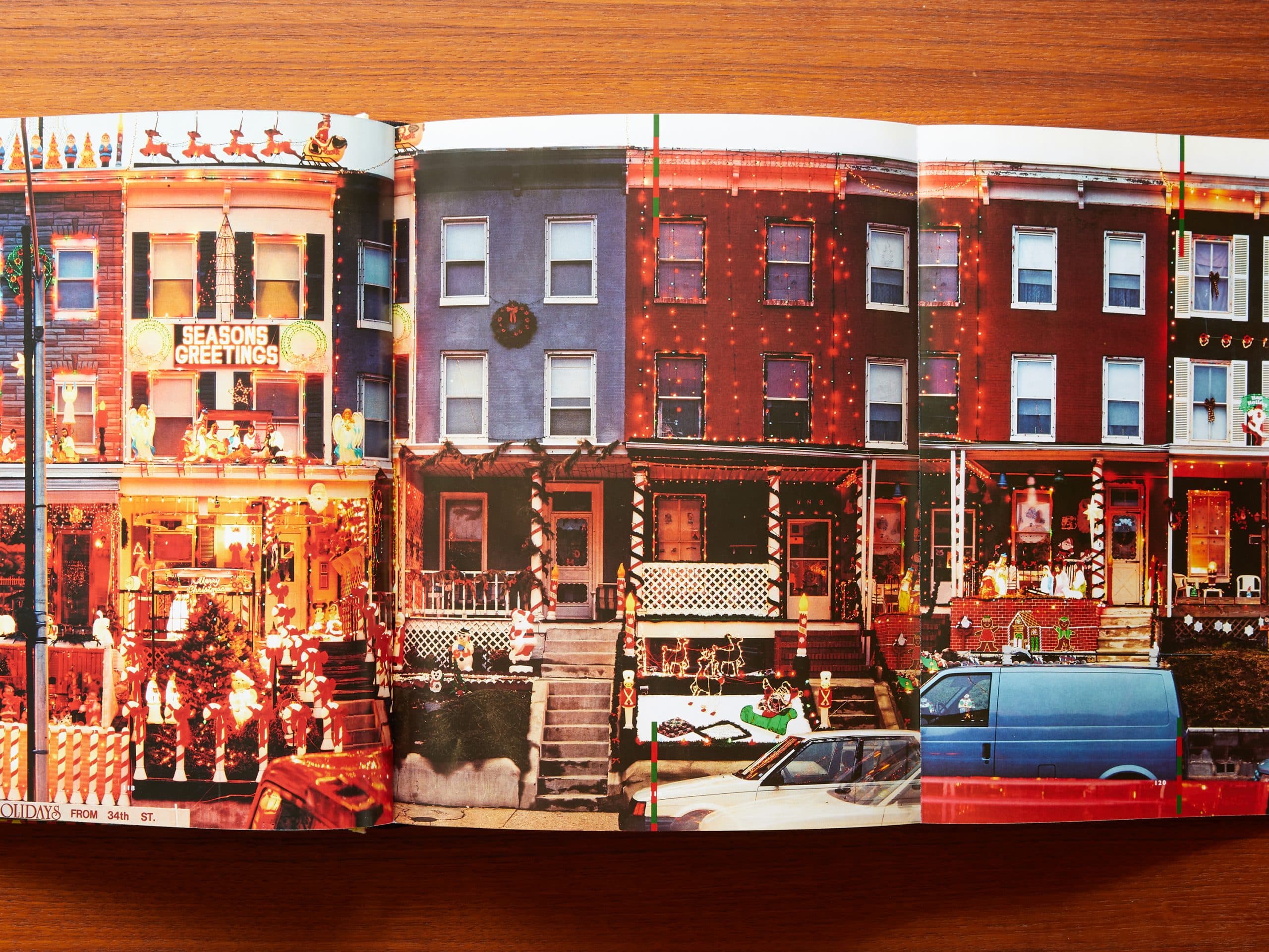

Picking up an issue of Nest, you might find a photo choked with fake sunflowers — adorning that synthetic Garden of Eden — or one featuring illuminated outdoor plastic Christmas reindeer from Kmart prancing on a Baltimore block of workers row houses lit up for the holiday at super-high wattage.

Celebrated architect Rem Koolhaas once called the magazine “anti-materialistic.” But this characterization misses the way Nest glorified a kaleidoscope of decorative objects, from fine design to consumerist pop at its most catholic.

“We explored interior decoration as an expression of the individual soul, a form of artistic expression like painting,” says writer Lisa Zeiger, who served as the magazine’s decorative arts editor for more than two years.

At the same time, Zeiger says, the quarterly’s editors didn’t want “interior decoration to become too academic. That dries all the frivolity and joie de vivre out of it.”

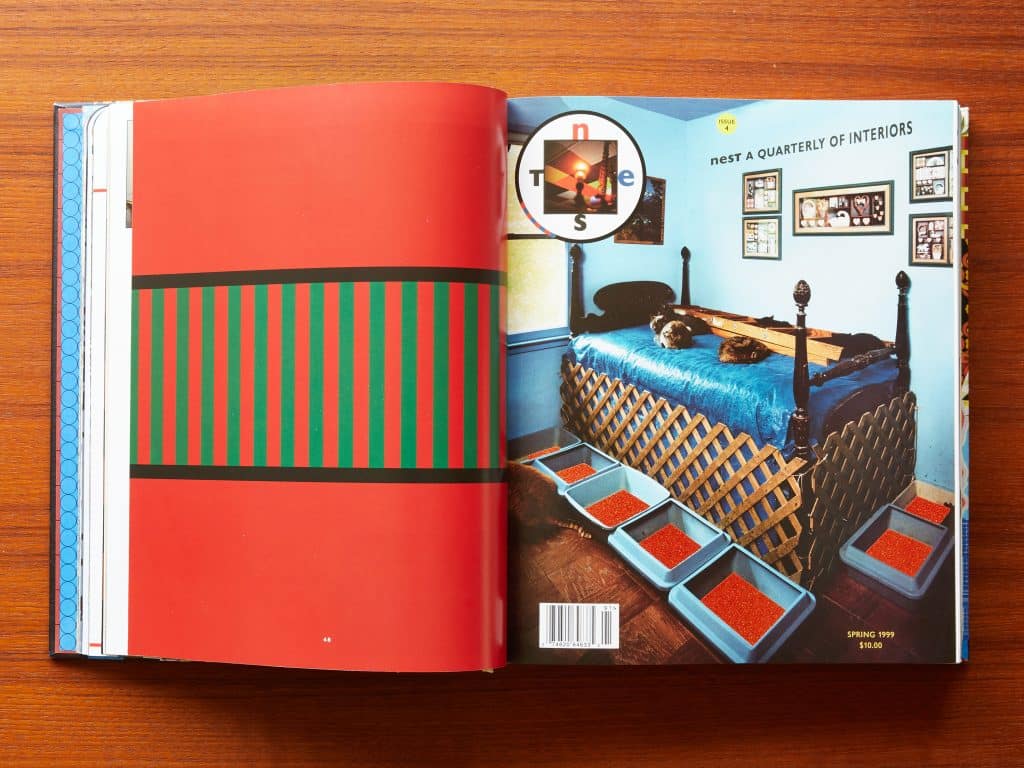

The magazine had both to spare. The spring 1999 cover shows a pineapple-finialed Colonial Revival four-poster bed in a tidy Tiffany blue townhouse bedroom in the Washington, D.C., suburbs, surrounded by seven kitty litter pans (the home’s owner had 144 cats at the time, down from an even more astonishing 171). Holtzman paid his printer extra to glue glinting red glitter inside each litter box.

Oldham insisted the book’s replica of the cover needed its own sprinkle of sparkles, too.

“I assure you nobody is walking away from this book with any money. We bothered to bother because passion counts,” he says, capturing not just the spirit of Holtzman’s original impulse but also the essential lesson of the entire Nest experiment.

Bring It Home

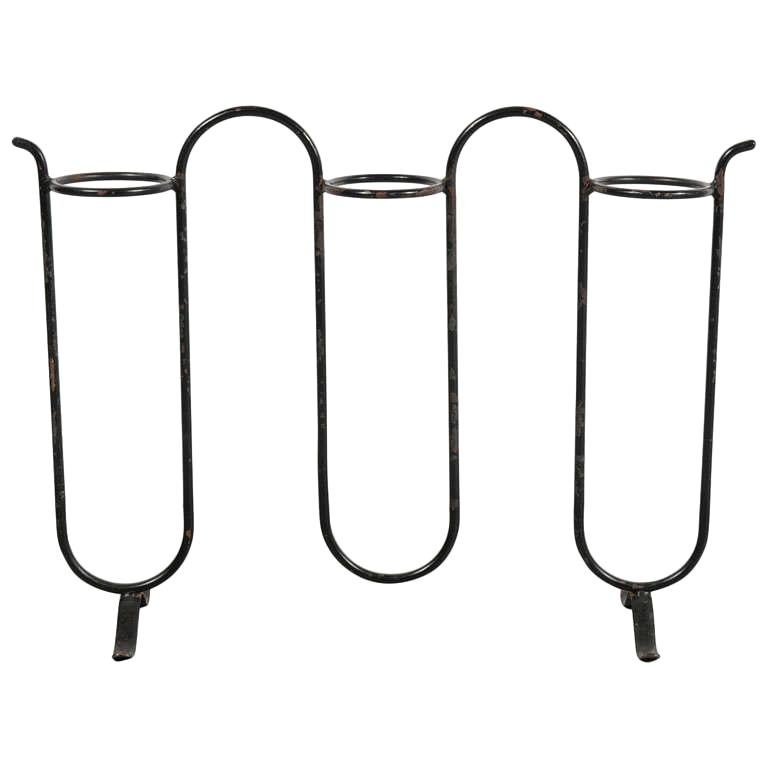

Channel the Nest look with items hand-picked by Todd Oldham