November 10, 2019Twenty years after her death, trailblazer Charlotte Perriand is getting long-overdue recognition for her contributions to architecture and design in the form of a large-scale exhibition at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, in Paris. Above, Perriand’s Bibliothèque from la Maison du Mexique, 1952. Photo courtesy of © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist.RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Claude Planchet. Top: Wearing a necklace of chrome-plated ball bearings, Perriand reclines on the now-iconic chaise longue that she designed with Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. Photo courtesy of © F.L.C. / ADAGP, Paris 2019 © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP

“We don’t embroider cushions here.” With this famous quip, Le Corbusier rejected the 24-year-old Parisian designer Charlotte Perriand, who had come to the maestro’s atelier in 1927 looking for a job. But Le Corbusier’s attitude changed a few months later when he saw Perriand’s gleaming installation Bar sous le toit (bar under the roof) at the Salon d’Automne. A reconstruction of part of her tiny attic apartment, with its aluminum and nickel-plated surfaces, glass shelves and leather cushions, it must have appeared to him an exquisite reflection of his belief that “a house is a machine for living in.” He hired her on the spot.

Perriand in Rio, 1987. Photo courtesy of © Adagp, Paris, 2019; © Archives Charlotte Perriand

Perriand spent the next decade working alongside Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret. The two men put her in charge of furniture and interior fitting, and she was soon creating many of the studio’s most iconic pieces of “equipment for living,” such as the adjustable pony-skin chaise longue, the cube-shaped armchair, the leather swivel LC7 chair. All of these, among the most famous furniture designs of the 20th century, were commercialized in 1930 under the three designers’ names, but in the 1960s, Le Corbusier used only his with the LC label.

Now, this visionary architect, urbanist, photographer and designer, who died at 96 in 1999, is getting her due in the blockbuster exhibition “Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World,” on view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, in Paris, through February 24, 2020. The show marks the first time the entirety of the sprawling Frank Gehry–designed building has been devoted to the work of a single artist, a fitting tribute to Perriand, who is finally stepping out from Le Corbusier’s long shadow.

This reproduction of Perriand’s 1934 Maison au bord de l’eau is on view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. Photo courtesy of © Adagp, Paris, 2019, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

“Shortly after Charlotte’s death, a friend told me that it takes about twenty years after the death of a creator to see his place in art history,” says Pernette Perriand-Barsac, Charlotte’s daughter and longtime collaborator, who is an architect herself and one of the exhibition’s curators. “I was baffled at the time, but now here we are, and it’s come true. There was all the more danger because the work of Charlotte, a woman artist, had been combined with that of the great gurus of modernity, Le Corbusier, Jeanneret and [Jean] Prouvé, whom she accompanied over the course of her long career — as if a woman couldn’t be independent, equal to or more relevant than a man in her chosen field.”

The exhibit features a reconstruction of the exhibition “Proposal for a Synthesis of the Arts,” which opened in Tokyo in 1955. For the show, Perriand collaborated with Fernand Léger and Le Corbusier, as well as with Hans Hartung and Pierre Soulages, designing a space that brings together paintings, sculptures, tapestries, furniture and architecture. Photo courtesy of © Adagp, Paris, 2019, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

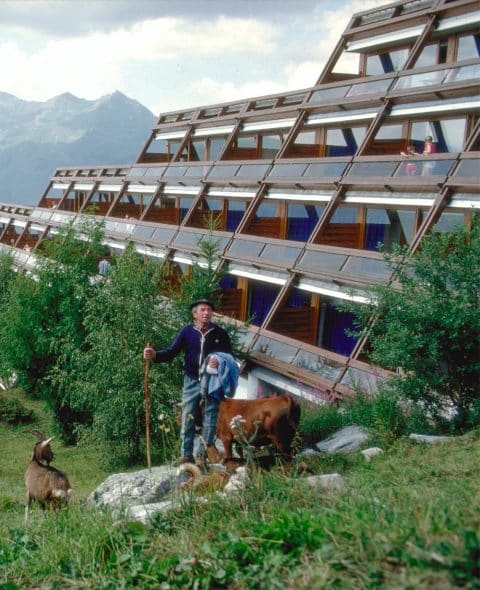

In the 1960s, Perriand pushed the boundaries of prefab to produce high-quality housing at low cost for the French ski resort Les Arcs. Photo courtesy of Archives Charlotte Perriand © Pernette Perriand

The show’s curatorial committee included Pernette’s husband, Jacques Barsac, an authority on Perriand and author of the catalogue raisonné on her work; Sébastien Cherruet, an architecture historian who is responsible for institutional relations at LVMH; and art historians Sébastien Gokalp and Gladys Fabre. “Most people think of her as a woman who just designed a few chairs with Le Corbusier,” Cherruet says of Perriand. “That’s totally incorrect, and it does an injustice to her work.”

The curatorial team imagined a rich and complex exhibition that explores beyond her furniture design. “She would tell journalists, ‘I don’t define myself — that would be too limiting. I’m a woman of art,’ ” her daughter recalls. The result is an “interdisciplinary dialogue,” says Cherruet, “that invites visitors not just to look at furniture but to immerse themselves in modernity, in the objects and photographs and spaces she created, as well as in her collaborations with painters such as Léger, Picasso, Miró and Calder.” These are among the 15 artists whose creations, often featured in Perriand’s interiors, are showcased in the exhibition alongside 200 of her designs, models, sketches, plans and photographs. Visitors can see another 200 works and objects by these artists, as well as designs by several other designers, from Le Corbusier and Jeanneret to Prouvé, with whom she collaborated closely after World War II.

This cartoon for a tapestry after Pablo Picasso’s 1937 painting Guernica was created at the request of the artist and realized in 1955 by Jacqueline de la Baume-Dürrbach and René Dürrbach. Photo courtesy of © Succession Picasso 2019, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Felix Cornu

The exhibition brings Perriand’s work to life with several meticulously researched reconstructions that allow visitors to enter and use the spaces she imagined. Among these is the 1927 Ideal Apartment, a loft-like residence-cum-studio, filled with her strikingly modern chrome tube furniture, which embodies the machine-age aesthetic she championed. Visitors can also climb into a re-creation of her visionary Barrel Refuge, a prototype for a prefab mountain shelter that she imagined with Jeanneret in 1938. Lightweight, compact and transportable, the ingenious aluminum-clad structure was never realized during her lifetime.

Perriand, Le Corbusier and Jeanneret’s Équipement intérieur d’une habitation, presented at the Salon d’automne 1929, was reconstructed for the exhibit by Cassina, Sice Previt and design historian Arthur Rüegg. Photo courtesy of © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019 © PJ / Adagp, Paris, 2019 © Charlotte Perriand / Adagp, Paris, 2019, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes

Other spaces include the student rooms Perriand designed in 1952 for the Maison de la Tunisie at Paris’s Cité Universitaire, which feature her iconic multicolor-lacquered bookcases; also on display are the videos, plans, sketches and models she created in the 1960s for the French ski resort Les Arcs, in which she pushed the boundaries of prefab to produce high-quality housing at low cost. One of the show’s highlights is her spectacular Maison au bord de l’eau (house at the water’s edge), a prefab vacation home on stilts posed outdoors in the foundation’s large, cascading fountain. Curatorial committee member Barsac calls the structure “a gem, revolutionary. She wanted to make a house for all the people, not just for the happy few.” Another showstopper is a Japanese tea house surrounded by bamboo trees, commissioned by UNESCO in Paris in 1993. Profoundly influenced by her travels in Japan in the 1940s, Perriand, then 90 years old, wanted the structure to be a place where “people could meditate and dream about a new golden age, a place humming with cultural exchange, as well as diversity and universality.”

Perriand, who was interested in prefabrication, collaborated with Jeanneret to design le Refuge tonneau, 1938, as a mountain shelter. Photo courtesy of © Adagp, Paris, 2019, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

Manhattan-based design gallerist Cristina Grajales, who was a friend of Perriand’s in the last years of her life, remembers her as “a formidable presence, simple and natural, so strong, so modern, even in her nineties.” Grajales made the designer’s acquaintance during her first (and only) trip to New York, in 1997, when, on the dealer’s suggestion, the Brooklyn Museum of Art presented Perriand with a lifetime achievement award.

This gallery at the Fondation Louis Vuitton features this reconstruction of Perriand’s 1955 Tokyo exhibition, “Proposal for a Synthesis of the Arts.” Photo courtesy of © Adagp, Paris, 2019, © F.L.C. / Adagp, Paris, 2019, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

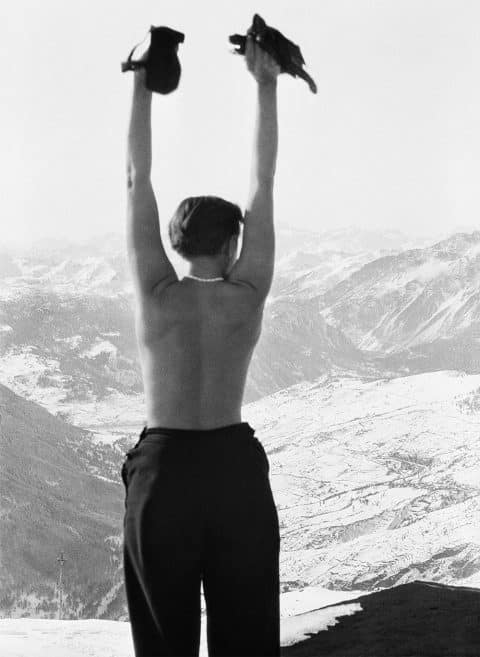

Perriand stands triumphant, facing a snowy mountain scene, in this 1920s image. Photo courtesy of © ADAGP, Paris 2019 © AChP

Grajales accompanied Perriand in Manhattan when she and a small group of her friends visited the UN building. “I was terrified about meeting her for the first time,” remembers the dealer, who decided to get Perriand a gift. “I saw a pair of Nike Air Max sneakers with reflective tape, and I thought, ‘They’re so modern, so advanced, I should get her a pair.’ ” She wasn’t convinced, however, that they were appropriate. Her doubts were put to rest when, after lunch at Brooklyn’s River Café (“ ‘If Corbu were still alive, he would have loved it, loved the frontality of the windows,’ ” Grajales remembers her saying), they boarded the Staten Island Ferry. “Upstairs,” the gallerist says, “we saw a beautiful young girl wearing those sneakers. I dared to tell her I’d wanted to get them for her. Without skipping a beat, she shot back, ‘I’m a size six.’ I bought them that same day, and she never took them off.”

It’s not hard to recognize that vital 94-year-old in metallic-striped sneakers in the exhibition poster, which reproduces a famous Perriand portrait from the 1920s. Her hair cropped in a short, boyish bob, she stands shirtless, wearing her famous necklace of chrome-plated ball bearings, atop a snowy mountain, arms outstretched, her bare back to the camera.“That photograph of a strong woman, triumphantly embracing nature, is the perfect image of my mother,” says Pernette Perriand. “She announces the contemporary woman, emancipated and free.”