February 16, 2025For a project in her hometown of Charleston, known for its hot jazz festival, the designer Betsy Berry played it cool in more ways than one.

Although the home, an 1803 neoclassical structure with Federal details, required a gut renovation, Berry showed great restraint, mixing mostly modern and contemporary pieces with carefully selected antiques while avoiding overstuffing the spaces. Instead, she flattered the original architecture and its ornate, traditional design elements by letting them speak for themselves.

She also kept her composure with her celebrity client, Darius Rucker, the three-time Grammy-winning lead singer of Hootie & the Blowfish, who’s also enjoyed solo successes during his nearly 40-year career.

In an introductory pandemic-era Zoom call with Rucker, she didn’t let on that she recognized him — and, even after getting the commission, kept mum about it for the two years they worked together.

“I acted like I didn’t know who he was until our last day,” says the designer, laughing. “But of course, I did — I’m a child of the nineties.”

A daughter of South Carolina’s Lowcountry, Berry studied at the New York School of Interior Design and worked in Manhattan for years, including stints with notable decorators James Huniford, Stephen Sills and David Easton. She founded her firm in 2015, and since then, it has grown from a solo operation to a team of nine people.

“Our style is rooted in architecture, and it’s very classic,” says Berry. “There’s a sense of beauty without making anything feel too fine. It’s luxury built on comfort, a lot of custom furniture and bespoke finishes and materials. Our rooms have a sense of place.”

Rucker’s home was built as a single-family house, with a brick facade that was replaced with a marble one around 1900. But for six decades before he purchased it, in 2018, it was owned by the Catholic Church and used as office space. Just turning it back into a residence took more than a year, a process that began in 2021

Rucker, who has three grown children, told Berry he wanted somewhere he could entertain family on a regular basis, but he didn’t say much more.

“I just really ran with it,” says Berry. “It’s amazing that he trusted me with the space.”

Rucker’s openness didn’t denote any lack of attachment to the project. “For him, this house is deeply personal, since he grew up in Charleston,” says Berry. “Having a place to gather his children and his extended family really meant something.”

The South’s complicated history was not skirted, but rather leaned into, says the designer, explaining that Rucker, who is Black, was mindful of the fact that “the craftsmanship of this home was most likely done by enslaved people. So, we wanted to preserve and celebrate that original work.”

Traces of the original work were everywhere but not always in perfect condition. Berry refurbished or re-created wherever possible.

“You could see what remained, and what we wanted to bring back,” she says. “If there was a piece of molding missing, we’d have that matched — we wanted to show off that craftsmanship.”

The team created a music room for Rucker in an unlikely place: a former pantry that the church had turned into a safe, with a massive bank-vault door. The extra-thick walls made the space a soundproof studio perfect for playing instruments and entertaining other musicians; here, instead of cleaning up areas of decaying plaster on the walls, Berry had a decorative painter extend the heavily patinated look.

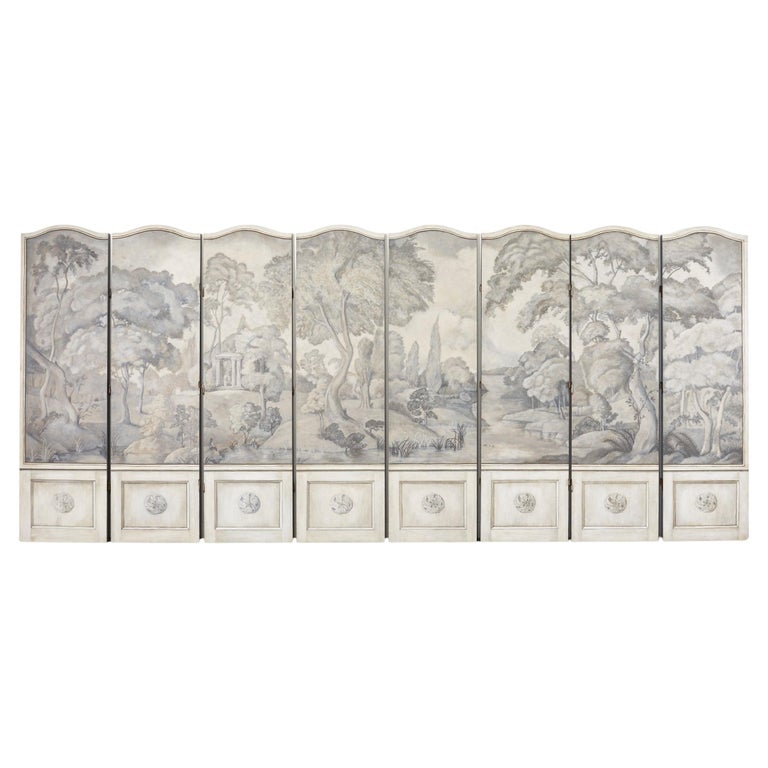

In all the main rooms, 1stDibs was a key source for Berry, who takes an eclectic approach with a period house.

“Darius wanted a bit more of this modern edge, so I mixed in vintage pieces and antiques as much as I could without making it feel too dated,” she says. “I love to add them in, especially with a house of this age.”

In the living room, Berry replaced the Victorian paneling above the original carved-wood mantel with rectangles of antiqued mirror arranged in a Piet Mondrian–esque pattern and set an abstract artwork by Yvonne Robert in front of them. “You can’t time-stamp this look,” the designer says of the aesthetic she created here and throughout the house, which doesn’t refer to a particular period.

Her 1stDibs picks in the living room have a distinctly Danish cast: a pair of Egg chairs by Arne Jacobsen for Fritz Hansen from around 1956 and a 1941 beech-and-seagrass lounge chair by Frits Schlegel, all of which stand out against the simple linen drapes and wool rug.

“I love Scandinavian design because I love clean lines. And here, it balances out the elaborate moldings — it provides a masculine element in a room that could be more feminine,” Berry says, referring in particular to the detailed millwork and ceilings and a curving wall whose windows overlook the yard. “I really pared back the decorative finishes here to show off the architecture.”

Much of the design drama lies in the dining room, whose darker, color-saturated look is meant to contrast with the “light, bright and beautiful” kitchen, with its marble counters and oversize custom range hood.

““Our style is rooted in architecture, and it’s very classic,” says Betsy Berry. “There’s a sense of beauty without making anything feel too fine.”

“I always think about the tension among rooms,” says Berry, noting that the dining room and the kitchen sit across the entrance hall from each other. The former is clad in amethyst-hued wallpaper applied in brick-like sections. It looks out on the street, so anyone peering through its window, notes the designer, “can see the color in the evening.”

Berry suspended a Lindsey Adelman blown-glass light fixture with brass clamps above the custom mahogany dining table — a relatively unfussy and modern form evoking the past ever so delicately with antique brass caps at the base of its legs. She created the simple dining chairs herself, covering their seats and backs with a tufted icy blue linen.

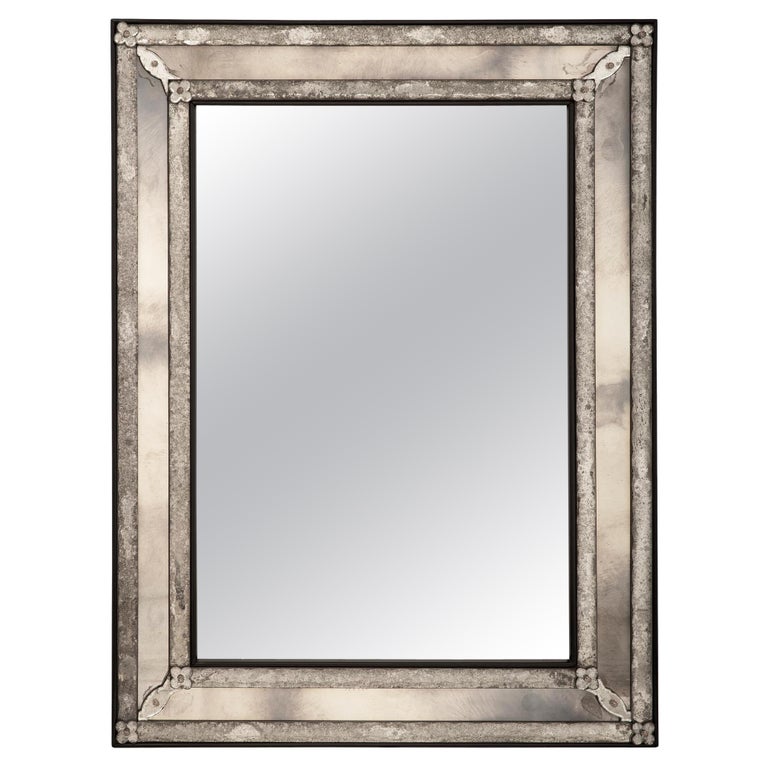

For the wall over the original Federal-style mantel, Berry discovered on 1stDibs a strikingly contemporary piece: a concave mirror with an ebonized frame. The site was also the source of a circa 1970 coral-stone and gold-leaf lamp, which sits atop a 1920s English mahogany sideboard.

The primary bedroom is above the living room and has the same striking curved wall; for both spaces, Berry crafted a herringbone-patterned floor from reclaimed oak. Among the mix of furnishings, Berry included some masculine accents — a leather-wrapped bed and a Holly Hunt leather and alabaster light fixture — softened by a gray silk wall covering.

From 1stDibs, she added a contemporary Turini & Werich console with a brass base and an inset black marble top, which she placed against one wall, and a 19th-century Napoleon III–style mirror, hung over the mantel.

“It creates this tension of feminine and masculine, but also of modern and classic,” says Berry, describing her choices in the bedroom and elsewhere. “And that’s exactly the balance I tried to create with the entire house.”