November 3, 2019Being ahead of your time can be a good thing or a marketing disaster. Many designs we now take for granted needed time to be accepted by consumers. Some looked too different or were made of strange new materials, some seemed difficult to use, and some just didn’t seem necessary. A few were so avant-garde that they couldn’t be made with existing technologies.

On view through March 8, 2020, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), “Designs for Different Futures” celebrates works that anticipate the needs and desires of generations to come. The exhibition includes Resurrecting the Sublime, 2019 (above), a collaborative project that combines cutting-edge scientific research and immersive installations (photo by Juan Arce, courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2019). Top: The Finnish studio Lundén Architecture Company adapted and reinstalled its Another Generosity, which debuted in the Nordic Pavilion at the 2018 Venice biennale, for the PMA show. In the words of its designers, the work “explores the relationship between nature and the built environment, and how architecture can facilitate the creation of a world that supports the symbiotic coexistence of both” (photo © Andrea Ferro).

The children’s clothing line Petit Pli, founded by Ryan Mario Yasin, features outfits that grow with the wearers to fit them from the age of nine months to four years. Photo © Ryan Mario Yasin

A provocative exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art seeks to demonstrate the essential role that designers, with their propensity to look beyond the present, play in shaping how we think about what lies ahead. “Designs for Different Futures,” on view through March 8, 2020, includes some 80 works, many of them more conceptual than practical, that address current challenges and ones we can expect in the years to come, exploring how design can influence our interactions with the world around us. The show includes practical objects — new sneakers made from pieces of old ones, children’s clothing that gets larger as they grow, a digital identity card, textiles made of seaweed — plus more esoteric ones, like artificial organs, a farm for raising edible crickets, a gene-editing kit and laboratory-grown foods.

Although much of the exhibition deals with issues relating to a future seemingly too remote for them to be relevant to our lives today, it’s an important reminder that designers have always tended to look ahead, and especially so since modernism, with its mandated a rejection of the past, took hold. Ironically, ideas and technologies from previous times have not only played a role but found new life or wider acceptance in forward-looking designs, some considered ahead of their time and now in everyday use or valued as collectibles.

The folding chair was considered ahead of its time, with no place in interior decor, when it was invented in 1947. This version, from around 1949 and made of tubular steel and cotton cord, is by Greta Magnusson-Grossman and currently on offer from Weinberg Modern.

The folding chair, for example, was invented in 1947, though its origins can be traced back to the folding stools of ancient Thebes. Functional rather than aesthetically pleasing, it had little place in interior decor until Ikea popularized the idea of “knock-down” furniture. The design was then adopted and upgraded by enough producers that nowadays, folding chairs of all varieties are familiar furnishings in most homes.

Plastic, the dominant material of our time, was invented in 1869 as a substitute for ivory in billiard balls. Called celluloid, because its base was cellulose, it was followed in 1907 by the completely synthetic Bakelite, which was developed to replace shellac but whose true niche was fashionable costume jewelry. Still used in colorful pieces today, the material is almost as popular as during its heyday, from the 1930s through the ’50s.

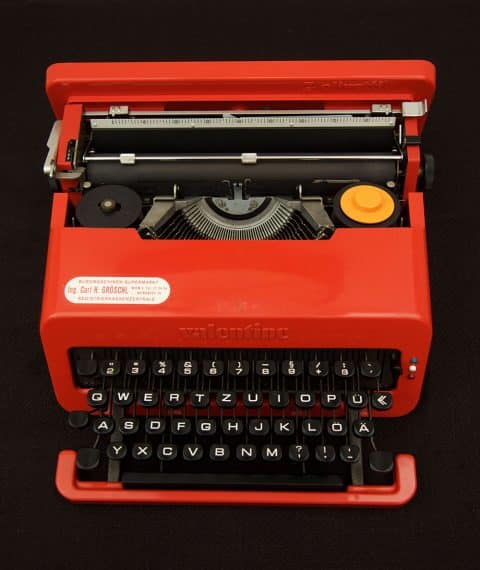

In the age of computers, the venerable typewriter is a rare and sought-after collectible. It’s ancestor was a 1714 English writing machine that sought to adapt the idea of the printing press to personal use. Edison developed the first electric typewriter in 1872, but the devices didn’t come into wide use until the 1950s, and Remington introduced the first commercially practical one in 1974. Nowadays, vintage examples are showcased in museums.

In its early days, the typewriter also seemed intended for a future the public couldn’t quite foresee. This Valentine model, by Ettore Sottsass for Olivetti, dates to the 1960s and is on offer from Galerie Zeitraume.

One of the icons of modern design, Verner Panton’s S-Chair was designed in 1960 but not produced until 1967: The first chair to be made from one continuous piece of material — fiber-reinforced plastic — it was originally deemed too difficult to make, and its graceful form appeared unstable to many consumers. Ray and Charles Eames’s La Chaise faced an even longer delay between drawing board and realization — not because its manufacture was too complex but because it was too expensive. Designed in 1948 for a Museum of Modern Art exhibition, it was finally produced in 1996. Today, it’s a modern classic and has spawned a slew of similar pieces.

Several designs now sought after by collectors and vintage-furniture fans were considered too extreme when they first came on the market. Arne Jacobsen’s Egg chair (1957) and Eero Aarnio’s Ball chair (1963), for example, became popular only after their appearance in national advertising campaigns and futuristic films and television shows made them seem less fantastical and more trendy-modern.

Because of the cost or complexity of their production, or their unusual look, these chairs’ transition from drawing board to people’s homes took time. From left, Verner Panton’s molded S chair was designed in 1960 but not distributed commercially until 1967; Eero Aarnio’s Ball chair, from 1963, became popular only after featuring in national advertising campaigns and in films and television programs; designs by Sottsass and his Memphis Group, such as the Westside lounge chair for Knoll, 1983 — this one on offer from Retro Inferno — encountered similar hurdles.

The Italians have long led the pack in avant-garde modern design. The baseball-mitt-style Joe (1970) and the inflatable Blow chair (1972), both designed by Jonathan De Pas, Paolo Lomazzi and Donato D’Urbino, were among the notable innovations of postwar Italian designers, but they took time to be accepted as more than mere novelties. Some of the Italian creations were both innovative and political. Gaetano Pesce, for instance, designed his Up chair, which was shipped in a three-inch flat carton and expanded when unpacked into a bouncy round of foam, to symbolize the oppression of women. The radical, postmodern pieces created by Ettore Sottsass and his Memphis Group in the 1980s, with their jazzy patterns, bold colors and laminate-covered surfaces, were considered bizarre when introduced but were later embraced — both by a new generation that had never seen them and by older design connoisseurs who liked them better the second time around.

Like Aarnio’s Ball chair, Arne Jacobsen’s 1957 Egg chair didn’t win the public over until appearances in movies and on TV made it seem less fantastical and more trendy-modern. The pair of Egg chairs and matching ottomans seen here is currently on offer from Retro Inferno.

Lighting, of course, has made extraordinary advances in the past several decades, and LED (light-emitting diode) illumination is considered the most advanced technology of all. Its development began, however, in the early years of the 20th century, with experiments in electroluminescence that produced light too faint to be practical. The first usable LED was created in 1961, and the lighting came into general use in the 1980s, primarily in avant-garde Italian designs, many of which are still sought after.

Ray and Charles Eames designed La Chaise in 1948 for an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Because of the expense of its manufacture, it wasn’t released to the public until the 1990s, when Vitra began making it.

No matter how forward-thinking consumers may become, designers will always stay ahead of them, looking for new ways of working with materials and exploring new techniques. For centuries, they’ve been using their imaginations to make objects that had never been seen before — that we didn’t even realize we needed or wanted. And isn’t that what design is all about?