August 21, 2017“It’s the interaction with the clients, the furniture gallerists and the art dealers that makes my life so very interesting,” says designer Douglas Mackie (portrait by Philip Sinden), “particularly when a client is open to pushing the boundaries.” Top: Mackie finished a drawing room in London’s Holland Park with a 1950s Japanese screen and an Hervé Van der Straeten lamp (photo by Gary Hamill).

Douglas Mackie likes to draw. The British designer, known for his elegant, highly eclectic yet oh-so-comfortable interiors, has always had the knack, but he perfected his technique during a class trip to Rome when he was an architecture student at Cambridge. From early morning until the last light of day, he drew every classical wonder he saw. “I still have my notebooks,” he says, “and you can see how I improved over those ten days, from our first stop at Francesco Borromini’s Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza to our last at Donato Bramante’s Tempietto on the Janiculum.”

True to that early grounding in classicism, Mackie has made drawing a central tenet of his interior design practice. “Drawing trains the eye,” he says. “There’s a wonderful ambiguity you can get from a rather loosely rendered pencil drawing. It’s so much more evocative when exploring what a space can be like, and that can’t be replicated with one of those computer-generated images.”

You might say drawing changed Mackie’s life. In the mid-1980s, he spent a gap year in New York between his undergrad and graduate studies working for an architecture firm and moonlighting as a draftsman for interior designers. The job afforded him entrée into some of the city’s grandest apartments. He was wowed by their drama and sophistication, not to mention their daring juxtapositions of styles. “Each element was very strong,” he remembers. “Individually, they had powerful personalities and were put together by people who know how these things are done, which is not something you are born with but something you acquire through experience. That period in New York probably had the greatest influence on my path from architecture to interior design.” Although Mackie returned to Cambridge, he says he finished his degree “halfheartedly.”

In his own country home — a manor on the outskirts of London — Mackie hung an André Arbus chandelier from Galerie Yves Gastou over a custom cashmere rug by Luke Irwin. A T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings chair sits at the desk. Photo by Jan Baldwin

After graduating, Mackie worked for a time as a draftsman before getting a job with Tessa Kennedy, one of London’s decorating grande dames, known for her romantic and eclectic style. Five years later, in 1995, he set off on his own, and it wasn’t long before he made a name for himself and his eponymous firm. His interiors mixed the modern and the classical, much in the manner of Albert Hadley, one of the New York designers he most admired. But to this mix he added an extra sensitivity to the art and objects, colors and textiles in the room, as if he also had a more contemporary-minded Sister Parish in his aesthetic DNA.

Mackie describes his approach to interior design as highly intuitive. “After an intelligent and informed dialogue with a client to establish a direction, I might start with some cultural reference of the client’s, a treasured artwork or piece of furniture,” he says. “Sometimes, I’ll find a remarkable object at a dealer or a painting with rare power and go from there.” He sketches out his ideas in pencil or with watercolors and then presents them to the client for approval. More often than not, the room turns out much like his original rendering.

Mackie recently rebuilt a house in London’s Chelsea district — which, he says, had been “eviscerated” of all architectural detail — designing the interior to resemble that of a Tudor-style mansion à la Edwin Lutyens, featuring handsome joinery and decorative ornament. He has also composed the rooms of an English country house in Gloucestershire with the quiet and restraint of Jean-Michel Frank to serve as the backdrop for the client’s growing collection of important 20th-century British art. And he has decorated a double-fronted terrace house in Notting Hill with a combination of period and contemporary furnishings, along with Asian, Western and tribal art, all displayed together with a panache worthy of one of the great New York decorators he admired in his youth.

A Maison Jansen screen, a Carl Malmsten daybed from the 1940s and a pair of custom pen-shell nightstands adorn the master bedroom of Mackie’s Marylebone home. Photo by Simon Upton

“I approach every project as a fresh start,” says Mackie. “That’s what makes life consistently more interesting. It’s why I don’t repeat a color scheme. Maybe it would be more financially astute to use the same palette over and over again, so that clients could just come to me for that look. But that’s not why I’m an interior designer. It’s not what I do. It’s the interaction with the clients, the furniture gallerists and the art dealers that makes my life so very interesting, particularly when a client is open to pushing the boundaries and doing something very different.”

It’s also why he commissions pieces, collaborating with such dealers as London’s David Gill, New York’s Cristina Grajales and Paris’s Yves Gastou. “Their taste and curation are fundamental to making the design process fresh, fascinating and stimulating, both for ourselves and the clients,” he explains. “I have such a debt of gratitude to these gallerists for breaking boundaries and exploring and introducing us to designers we simply wouldn’t come across. Without them, our work would be almost impossible.”

Despite his versatility, certain clues help to identify a Douglas Mackie interior. You can scout out the presence of one of the low tables of his own design, which have architectural-looking bases, or his super-luxe consoles and benches made using rare veneers and precious stones. (He produces these furnishings only for clients.) Or you can look for bold juxtapositions of resonant abstract artworks with striking tribal textiles.

In the high-ceilinged library of the Chelsea residence, early-19th-century Russian chairs surround a 19th-century English table. Mackie bought the 19th-century English bookcase at an auction. Photo by Gary Hamill

Mackie developed a penchant for textiles while working for Kennedy, who, he says, taught him about their “real aesthetic quality.” That is why today he often commissions custom fabrics for his projects. But Mackie became enamored of tribal weavings during a stay at the late Alistair McAlpine’s ancient convent-turned-B&B, in the southern Italian region of Puglia, where the walls, floors and furniture were covered with henna-dyed, “hint-of-a-Rothko” North African textiles and Moroccan rugs. He quickly recognized how the modern quality of their abstract designs could make them important elements of decor. To his mind, the best pieces can pack the same punch as a great work of abstract art — and are made further attractive by the fact that they can be acquired for a fraction of the price.

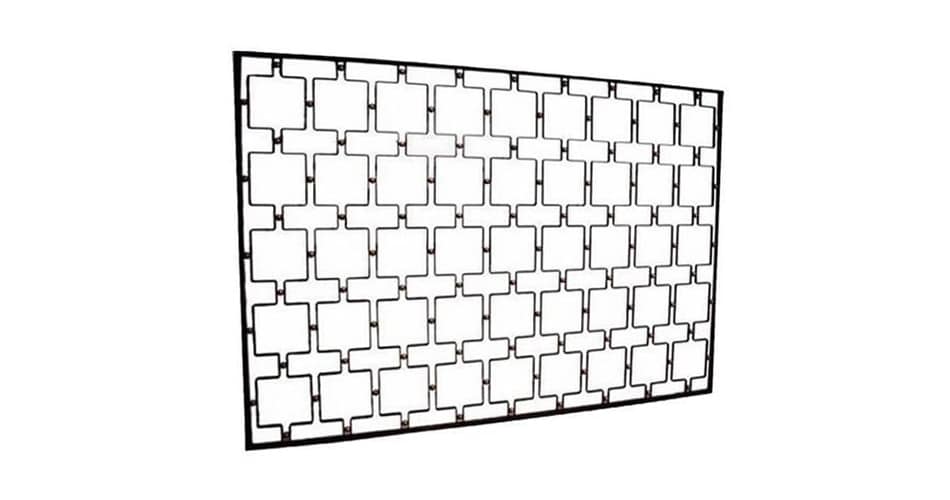

His appreciation for textiles with a strong sense of color and abstraction has led him to become interested as well in 20th-century Swedish textiles. In fact, he recently bought a large selection for a current project from the Stockholm gallery Modernity. But the textiles he uses most extensively are the cutting-edge rugs of the Colombian architect Jorge Lizarazo and his Bogotá-based company Hechizoo, which specializes in fabrics with complex geometries woven using brilliant colors and metallic threads. “These rugs approach that point of becoming art,” says Mackie. The same might be said of his interiors.