May 9, 2021Before the Industrial Revolution, the night was lit by the moon and stars or fire, or it wasn’t lit at all. Electric lighting changed lives profoundly, and the credit doesn’t belong to Thomas Edison alone.

Starting in the 1800s, a string of international inventors paved the way for the production and use of millions of incandescent bulbs by the dawn of the 20th century: Humphry Davy with his 1807 arc lamp; Werner von Siemens, whose 1866 discovery of the dynamoelectric principle made affordable electric supply possible; and Lewis Latimer, who improved the durability of Edison’s bulb and in 1890 wrote Incandescent Electric Lighting, the first book on the subject.

But function alone has rarely been enough for humankind; we have always preferred our objects of use to take beautiful forms. And so the art of lighting design was born.

The history and evolution of lighting design from the late 19th to the 21st century is the subject of a wonderfully titled exhibition, “Electrifying Design: A Century of Lighting,” on view through May 16 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and traveling to Atlanta’s High Museum of Art in June.

The information-packed and visually stunning show makes the case that everyday, often-overlooked lamps echo, reveal and in many ways propel cultural revolutions in leisure, science, art, business and government, all the while wrapped in stylistic attitudes like the truth-to-materials minimalism advanced by W.H. Gispen or the contemporary embrace of glorious excess exemplified by Moooi Works’ Mega Chandelier.

From the simple glass globe on a stem created by Wilhelm Wagenfeld in 1924 and the lacquered industrial designs of fellow Bauhaus adherent Marianne Brandt to the Machine Age collaboration between W. D. Teague and Polaroid, the show stresses the intimate connection between the evolving technology of illumination and inspired design.

Engaging engineers, scientists, architects and designers alike, the field of lighting became a major proving ground for state-of-the-art materials like plastics, inventive new mechanisms and emotionally resonant styles that included the ethereal (Isamu Noguchi’s Akari lamps), the whimsical (Gino Sarfatti’s 2109 Ceiling Light) and the eclectically postmodern (Achille and Pier Castiglioni’s Toio floor lamp).

Here, exhibition organizers, lighting enthusiasts and longtime friends Cindi Strauss, the curator of decorative arts, craft and design at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Sarah Schleuning, senior curator of decorative arts and design at the Dallas Museum of Art, talk with 1stdDibs about tracking the story of the naked bulb’s metamorphosis into an art form and selecting the best examples of the sleek, futuristic and lyrical lighting trends that have illuminated our world for the past 100-plus years.

How did your collaboration evolve?

Cindi Strauss: Sarah and I have been friends and collaborators for two decades. We had this idea percolating for many years, and finally in 2016, it began to take shape.

The show was born from us noticing that the lighting objects in the Houston museum collection seemed to touch so many aspects of daily life and so many stylistic movements. Plus, we both realized there was a dearth of exhibitions on this genre of design.

Who are some of the designers you chose?

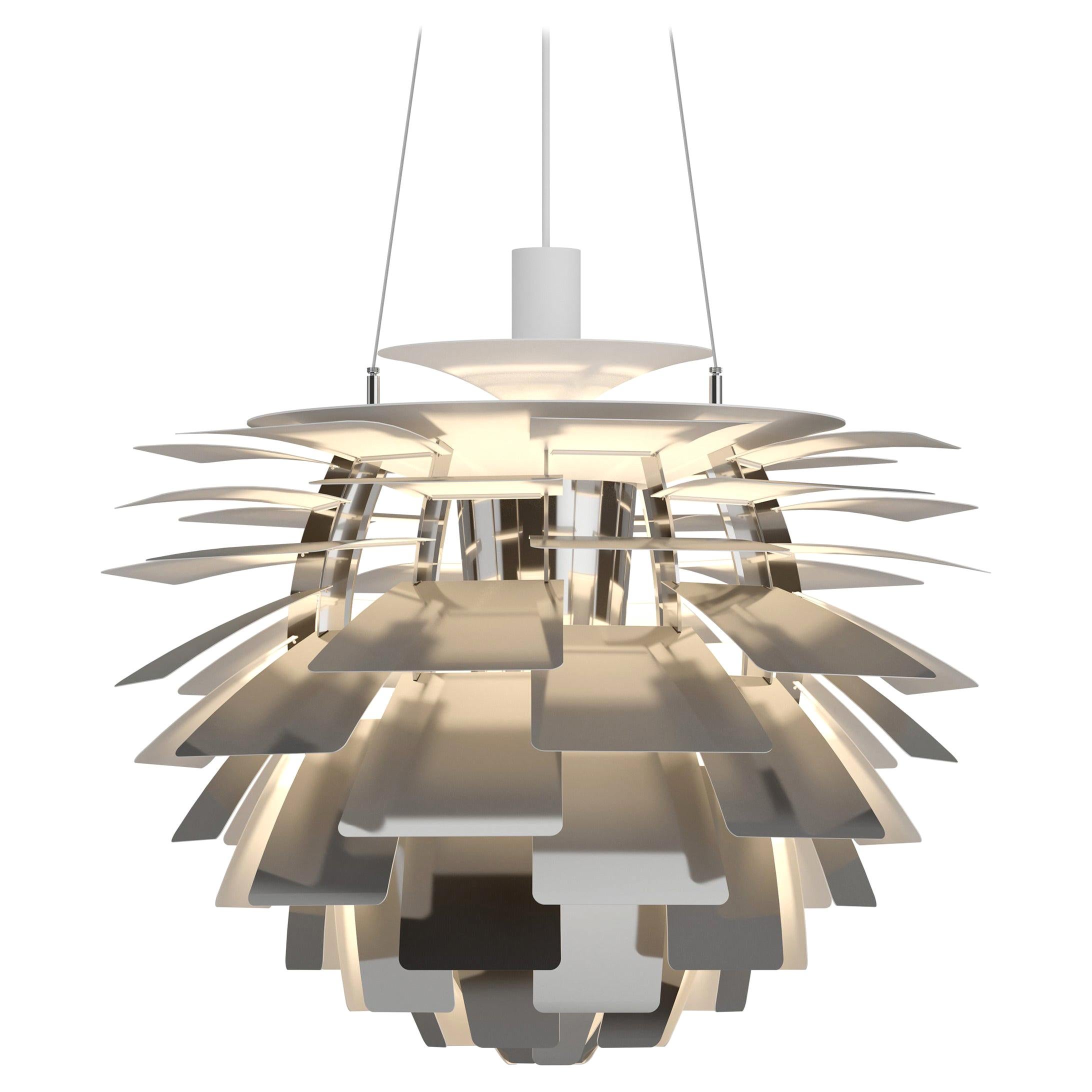

Sarah Schleuning: Poul Henningsen, Verner Panton, Greta Magnusson Grossman, Ingo Maurer, Achille Castiglioni, Christian Dell and Gino Sarfatti, to name a few.

C.S.: We decided to focus on leading designers and rare examples of their work — basically lighting objects that were produced in limited series.

This show sits at an interesting intersection of history, science and extremely good design.

C.S.: We wanted a holistic approach, with an international perspective and key designers, but not a comprehensive survey, which frankly would have been a daunting task, because this history is so complex.

Rather than work chronologically, we organized the show in three sections. “Typologies” focuses on different types of lighting, “The Bulb” looks at contributions and design related to the lightbulb, and “Quality of Light” considers the manipulation of light effects, including reflection, diffusion and light-filled sculpture.

Can you explain what you mean by typologies?

C.S.: It refers loosely to categories of use and types of environments — floor lighting, task lighting or chandeliers, for example. So within each type of lighting, the viewer could see a wide variety of use solutions and inventive approaches.

Can you give an example of an object in the section called “The Bulb”?

S.S.: We have Ingo Maurer’s first notable work, Bulb Light. It features a standard tungsten bulb housed in an oversize glass bulb. The exterior bulb enshrines the inner one and eliminates the need for a lampshade, reflector or diffuser, making the bulb itself the central design and functional element.

The scale is exploded, but he maintained the purity of the form and its elements while challenging the way a user typically interacts with a traditional bulb shape.

Is there a reason that you avoided a more linear or historical format?

S.S.: Loosely speaking, we wanted the viewers to be able to experience the unbridled creativity of this sort of design, to appreciate the objects just with their eyes, so that whether or not they’d read the catalogue or knew the history, they could just see the remarkable changes in materials and design strategies.

To paraphrase design scholar Bernd Dicke, quoted in your catalogue, lighting design runs the gamut from romantic escapism and decadent aestheticism to reformist zeal. Can you give a couple of examples of that continuum?

C.S.: Fragile Future 3.14 is a very whimsical, delicate lighting system by Dutch artists Lonneke Gordijn and Ralph Nauta, who founded Studio DRIFT in 2007. It incorporates actual dandelion seeds.

DRIFT often is commenting on ideas of ecology and our perhaps-disrupted connections to nature. What about the practical end?

C.S.: W.H. Gispen’s piano lamp — with its clean geometric lines, use of industrial materials and purposeful design — was chosen for its representation of the Dutch functionalist movement. The piano lamp is a typology that went out of favor after the mid-twentieth century, so it was also important to the narrative, to highlight the many typologies that previously existed.

You have some classic objects reflecting the mid-century modern sensibility. Can you comment on one or two?

C.S.: For American mid-century modern, the Lester Geis T-5-G speaks to the trends of the time — the diffusion of light through the use of perforated shades, directional light made possible by adjustability, geometric shapes, the preference for metal as the lamp’s primary material and the strategic use of color.

In addition, the emergence of modular and low-cost open-plan homes, as well as modern apartments and small-scale living in America, inspired the portability aspect of the designs. The material and color choices also dovetailed with furniture and home accessories produced by leading American design firms of the period.

There are objects that almost look like sculpture and seem to go out of their way to hide their function.

C.S.: We selected one Archizoom lamp for the show, the Sanremo. It was chosen to demonstrate the importance of lighting in the anti-design stance of the Radical Design movement [in Italy in the 1960s] and for its play on diffusion. It is an example of an atmospheric light that questions functional usage.

You’ve included some exquisite and rare examples by artists who have become household names. Can you talk about the lighting by Noguchi?

S.S.: Noguchi’s Akari lamp is both iconic and ubiquitous. In 1951, Isamu Noguchi visited Gifu, Japan, a town known for the manufacture of traditional lanterns made from mulberry bark paper and bamboo, and became inspired to design lamps that would be produced using the same traditional methods of construction.

Noguchi’s Akari lamp series combines modern aesthetics with traditional craft practices. The word akari means light as illumination and suggests a kind of weightlessness. Noguchi embraced this culturally specific definition of light and the potent possibilities of the materials. Alone or in large groupings, the Akari lamps possess a glowing, ethereal and almost magical quality that has made them popular lighting devices for decades.

It seems like even the most function-driven lamps strike a delicate balance between utility and beauty.

S.S.: Many designers played with scale and stripped components down to their most basic, functional elements. Jean Prouvé reduced the task lamp to a single globe bulb with his Potence d’éclairage (Swing Jib lamp), from 1952.

It projected out into the room at the end of a long metal pole. The effect is that a singular blob of light drops down to meet a specific user’s needs. Cantilevered more than eight feet off the wall, the rod easily pivots or swings as the user desires. Its utility belies the drama achieved by the combination of materials, color and scale.

C.S.: Several of the objects in the show are rare collector’s items and have not been plugged in, so to speak, in a very long time. The final section of the exhibition permitted us to work closely with engineers, who researched exacting historical facts about original requirements of wattage and wiring so that many of the lighting systems could actually be illuminated for the first time in decades.

Current viewers can experience the pieces in the way they were intended by the designers who conceived them and the people who used them a very long time ago. This is quite a treat that makes the lamps, their place in a broader history and their beauty come alive.