December 6, 2020Back in 2003, Franck Evennou received one of his most unusual commissions: a pair of large bronze doors adorned with a stylized motif of intertwining leaves and branches for a private chapel in Paris’s famed Montparnasse Cemetery, among the graves of Baudelaire, Brancusi and Man Ray. The chapel belongs to one of Evennou’s clients, for whom he also created a handrail for a villa in Saint-Tropez. Some 17 years later, Evennou still regularly bumps into the man. “Every time I see him,” Evennou recounts, “he says to me, ‘You see, I’m still not in there!’ ”

Evennou has numerous strings to his creative bow. He works as a sculptor but is perhaps best known as a designer, of furniture, lighting and, occasionally, jewelry. “I don’t make any distinction between fine art and the decorative arts,” he says. “For me, they are on an equal footing. I get the same pleasure from designing a sculpture as a fork or a coffee table.”

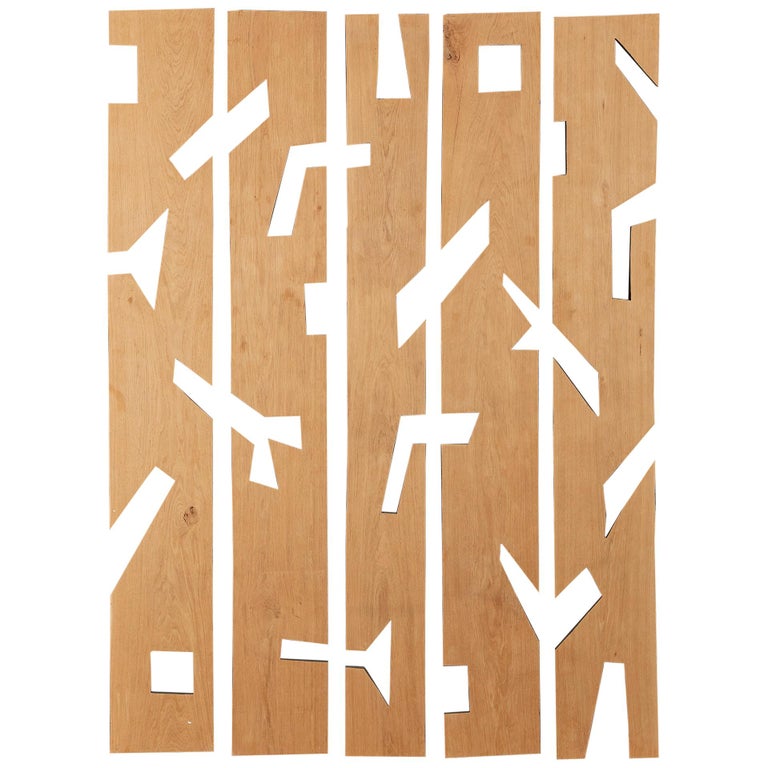

His approach to each, however, is quite distinct. He sculpts primarily in wood, favoring more geometric forms. His output includes small abstract carvings, wall panels with jagged shapes cut out of them and statuesque totems that are more than reminiscent of African art.

Evennou’s furnishings, meanwhile, are almost exclusively in bronze, which he pairs with materials like marble, crystal, alabaster and parchment. Their forms are more organic, derived mostly from the natural world. “It’s an absolutely inexhaustible theme,” he says. “The structures of plants — whether their branches, roots, pistils, flowers or leaves — are of tremendous beauty. They never fail to astound me.”

Both aspects of his production are presented in a joint exhibition wittily titled “Avenue Evennou,” on view through December 23 at both Bernd Goeckler and Maison Gerard, neighbors on Manhattan’s East 10th Street. Because of current COVID-19 restrictions limiting the number of people allowed in the actual gallery spaces, the displays are mainly in the windows.

Katja Hirche, the director of Bernd Goeckler, describes one of them as a “little flying window.” “We’ve suspended the tables so they appear to be tumbling in mid-air and placed other pieces in a more random fashion,” she explains. “It’s all black, with very dramatic lighting.” One of the highlights is a striking console with a Nero Marquina marble top and bronze legs shaped like elongated screws.

Across the street, Maison Gerard is unveiling a series of Evennou’s totems and a new collection. The latter includes a pair of alabaster and bronze sconces inspired by cacti and a trio of bronze nesting tables with tops shaped like leaves that Evennou has christened Taro tables, after the root crop.

“What I love about his work is that it’s both very whimsical and timeless,” declares the gallery’s director, Benoist F. Drut. Hirche, meanwhile, is drawn to the natural forms. “I also like the relatively unrefined finishes,” she adds. “The bronze is a little rough.”

Other fans include interior designers like Victoria Hagan, Robert Stilin and Jamie Drake. Architect Peter Marino has integrated numerous Evennou creations into Dior boutiques worldwide. A smattering of mirrors and occasional tables can, for example, be found in the Paris and Singapore flagship stores.

Similarly prestigious are a number of commissions Evennou has completed, such as a monumental door, a pair of torchères and an immense chandelier for the French ambassador’s residence in Beirut; a table incorporating a marble plaque given to Jacques Chirac by the King of Morocco, which found its way into the French prime minister’s official residence; and the high altar and liturgical furniture for the cathedral in Noyon, 60 miles northeast of Paris.

In person, Evennou has a strong and benevolent presence and exhibits a true zest for life. His passions include both poetry and archaeology, and his family environment is almost uniquely creative. His wife, Marianne Evennou, is an interior designer; his two sons, an actor and a tattoo artist. He was born in Paris in 1958 and brought up in a building near the Place de la Nation where his mother was born and still lives with his father. His paternal grandfather was a farrier, whose tools he inherited. “I have his anvil in my workshop and use it every day,” Evennou says. “He also created decorative objects out of wrought iron, which I’d watch him make. We had one of his floor lamps at home.”

Evennou was likewise influenced by regular childhood visits to the Palais de la Porte Dorée, which at the time housed a museum devoted to African and Oceanic art. “I thought it was extraordinary,” he recalls. “It was like being in an Indiana Jones adventure. It was mysterious and magical, with sacred statues everywhere.”

He embarked upon a full-time career as a sculptor at the age of 29. Before that, he worked for Kodak in Paris for a decade, but from his late teens, sculpture was a near obsession. He took lessons at 18 with an American teacher named Leslie Kaye. Among his first studios were the tiny cellar of the suburban house where he and Marianne lived in their young married life, as well as a house close to the Marne river without any heat, running water or toilet.

He recalls making early totems out of salvaged railroad ties. “I worked like crazy but ended up having to throw them all away,” he says. “I hadn’t realized they’d been treated with creosote, and they stunk to high heaven.”

Evennou segued into the decorative arts after starting to create furniture for himself. In 1989 he showed the results to a Parisian gallery that agreed to edit a collection of small objects, such as candleholders and boxes. His first solo exhibition came two years later.

His aesthetic has been remarkably constant over the years. “Nothing looks dated,” notes Maison Gerard’s Drut. “You’d be at a loss to know whether a piece is from yesterday or two decades ago.” Despite the organic forms, Evennou insists there is an underlying rigor. “Voltaire said that there is a form of geometry in all artists’ works, and that’s definitely the case with mine,” he says. “Everything is very structured. I hate embellishment and try to pare down my designs.”

For the past 25 years, Evennou has been doing just that from the workshop located in his home, a former industrial butcher’s shop in the city of Senlis, an hour’s drive north of Paris. He works there alone, without assistants, looking out onto a garden where a rosebush he and Marianne planted recently has grown quickly. It will act as the source of inspiration for his next creation: a bronze candleholder fitted with thorns. As with everything Evennou produces, the goal is for it “to be like a piece of poetry in three dimensions.”