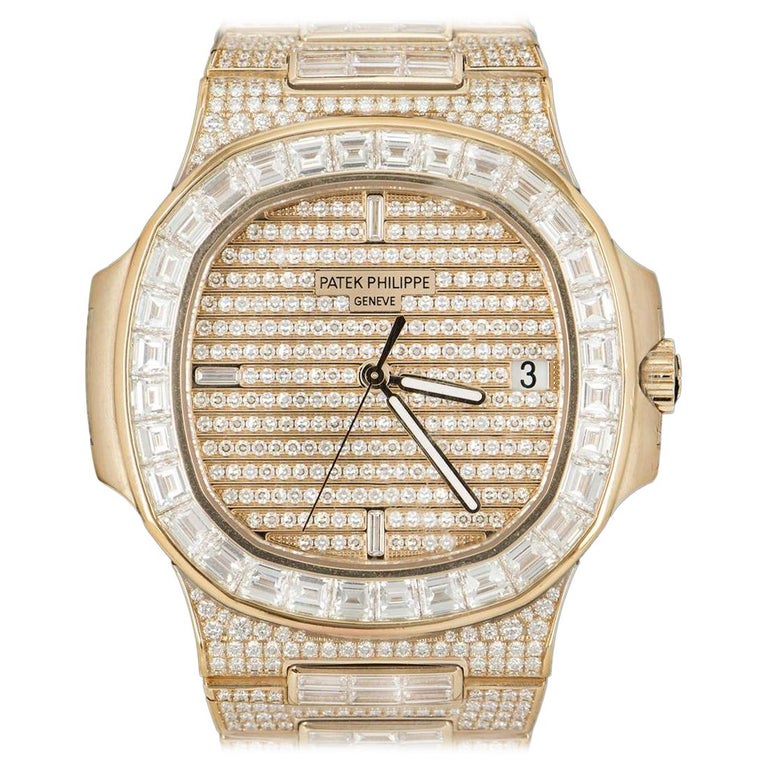

May 23, 2021In January, luxury watch brand Patek Philippe announced that its most popular model, the Nautilus reference 5711, was being discontinued after 15 years in production. The news caused shock and dismay among its many fans — particularly those on waiting lists, rumored to be upwards of a decade long, for the star of the 5711 series: the stainless-steel blue-dial 5711/1A-010. Almost instantly, the timepiece’s price on the secondary market exploded.

In an interview with the New York Times, company president Thierry Stern explained that the 5711 threatened to overshadow Patek Philippe’s other offerings and even the brand itself. He discontinued the reference — an industry term for the model number — to protect the brand and its other watches, including alternate versions of the Nautilus. “We cannot put a single watch on top of our pyramid,” he said, also citing a duty to preserve the value of the 5711 by limiting its production.

Fortunately, those in the market for a similarly standout piece have plenty of options. The Nautilus is just one of myriad watches conceived by the brilliant Swiss watchmaker Gérald Genta, who designed among the most striking timepieces of the 20th century.

Although some of his handiwork is obscure — or relatively so, like the Rolex King Midas — several pieces are still in production, and both contemporary and vintage models are wildly popular on the secondary market.

It’s safe to say that Genta radically changed contemporary watchmaking. As a designer and engineer, he transformed both the overall appearance of timepieces and how they function. He’s also one of the few watchmakers whose creations for brands other than his own earned him worldwide acclaim.

Genta, who died in 2011, would have celebrated his 90th birthday on May 1. The prolific designer claimed to have conceived more than 100,000 watches in his 50-plus years at the drawing board. His business partner and wife of 30 years, Evelyne Genta, confirms this, explaining that he created something new every day. “I have in my possession thirty-two hundred designs, all different,” she says.

A native Monégasque and Monaco’s ambassador to the UK since 2011, she also heads up the Gérald Genta Heritage Association, which she founded in 2019 to preserve her husband’s legacy. “If I had to define him in one word, he was an absolute artist,” she says. “Watchmaking was a way of expressing himself. It was really all about art.”

The subtlest details can spark a watchmaking revolution, and Genta had a knack for creating such nuance. The octagonal case for the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, introduced in 1972 and perhaps his best-known creation, was based on vintage diving helmets that attached to the rest of the suit with screws. Genta had a thing for screws, an affinity that resonated with the watch-loving public. The Royal Oak had eight of them arranged in a symmetrical pattern on the bezel.

The design caused a stir upon its release. But more importantly, it marked the first time stainless steel was used for a luxury sports watch, kicking off the now ubiquitous trend for sports-chic stainless-steel timepieces with steel integrated bracelets — metal watch bands designed to fit seamlessly, in terms of both aesthetics and function, with the case.

A few years later, in 1976, Genta created the Nautilus for Patek Philippe, continuing the stainless-steel sports-watch theme. This time, the soft-angled bezel was inspired by the portholes of transatlantic ships.

Raj Jain, founder of Watch Centre and Rich Diamonds, on London’s Bond Street, says those two classics alone have had a lasting impact on the Swiss watch industry. He notes how rare it is for a watchmaker to make such notable contributions to multiple brands while making a name for himself as well. Genta “designed two iconic watches,” says Jain, “and he did this as a freelance designer.”

Marcus Rosner, founder of PatekMonger, in Santa Monica, California, has been an authorized Patek Philippe dealer for 44 years and estimates he has sold between 300 and 400 Nautilus watches.

“Timing is everything, and what has happened is that stainless steel has become a prominent status symbol,” Rosner says, explaining that Genta’s innovation now rivals the more traditional gold watch as an emblem of success, especially among younger watch buyers.

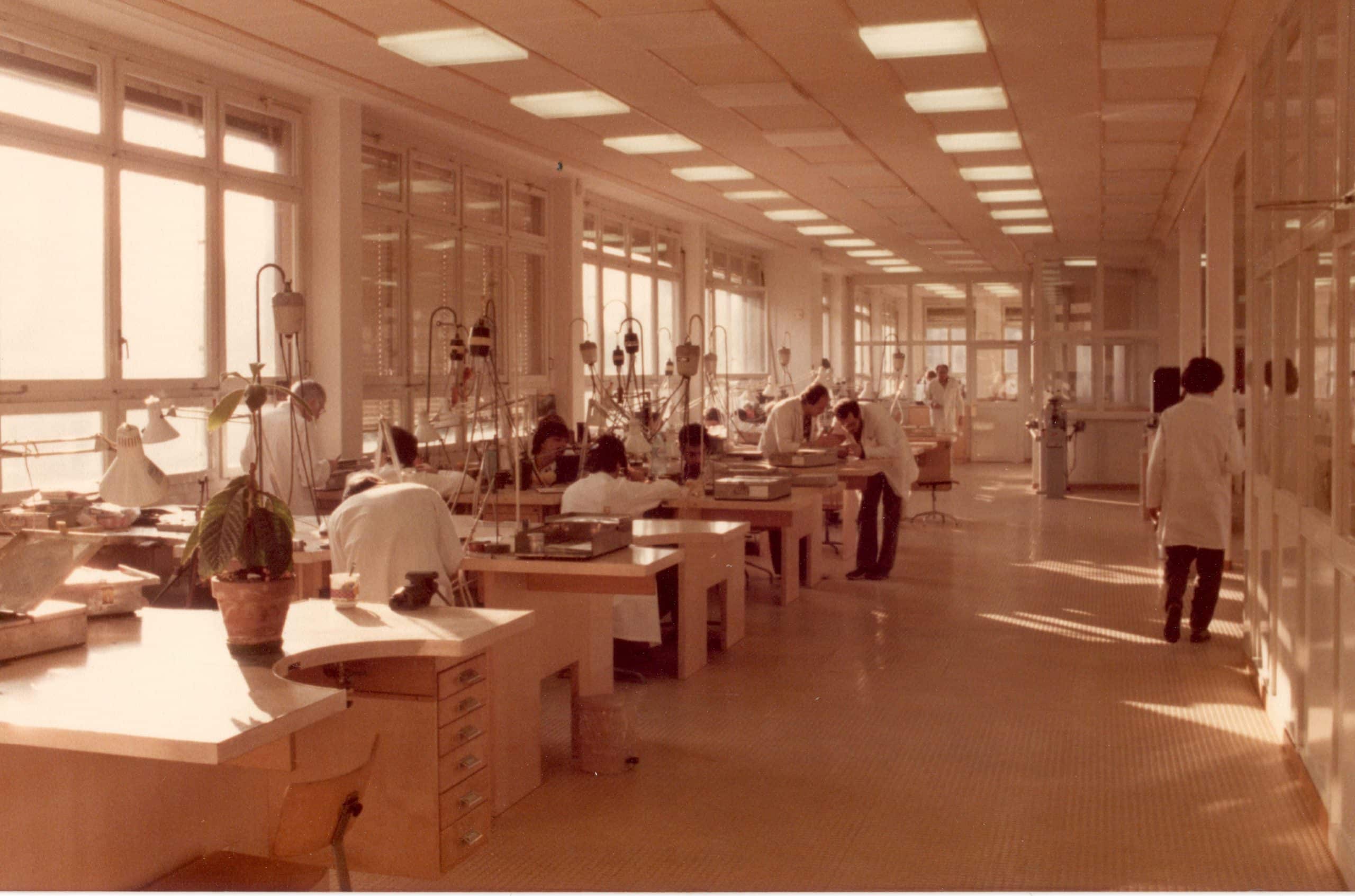

Born in Geneva, the capital of the Swiss watch industry, Gérald Charles Genta was hired by watch manufacturer Universal Genève at the age of 20 after finishing his training as a jewelry goldsmith. That his career would be in horology was pretty much set in stone when at 23 years old he was assigned to create a timepiece for Scandinavian Airline Systems (SAS) to celebrate its inaugural flight from Copenhagen to Los Angeles via the North Pole. The first models of the watch, named the Polerouter, were given to the cabin crew upon landing at Los Angeles International Airport.

Genta’s 1995 Grande Sonnerie, which emulated the chimes of London’s Big Ben, was at the time the most complicated watch in the world.

According to Genta’s wife, however, corporate life never suited him. In the early years, he would drive from Geneva to La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle, where the watch manufacturers were located, and sell his designs for 10 Swiss francs apiece. He would return home when he’d earned 1,000 francs.

“He was freelancing totally because he didn’t want a boss,” Evelyne Genta says. As a result, there are literally thousands of unattributed Genta timepieces in the marketplace.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s, he worked for Omega on its line of Constellation watches, which further cemented his position as a star designer. In 1958, his relationship with Patek Philippe began with the Golden Ellipse, whose oval case was a stylish departure from the house’s more serious, round Calatrava.

Joseph McKenzie, CEO of Xupes, a UK-based dealer in watches, jewels and handbags, points out that Genta created his most iconic designs in the 1970s — a difficult time for the Swiss watch industry, when Japanese battery-powered quartz timepieces challenged the primacy of traditional mechanical models.

“The one takeaway for many in the industry was his belief in great design and his willingness to push through adversity,” McKenzie says. “Let’s not forget this was the height of the quartz crisis, and this was also when the man and the industry came alive.”

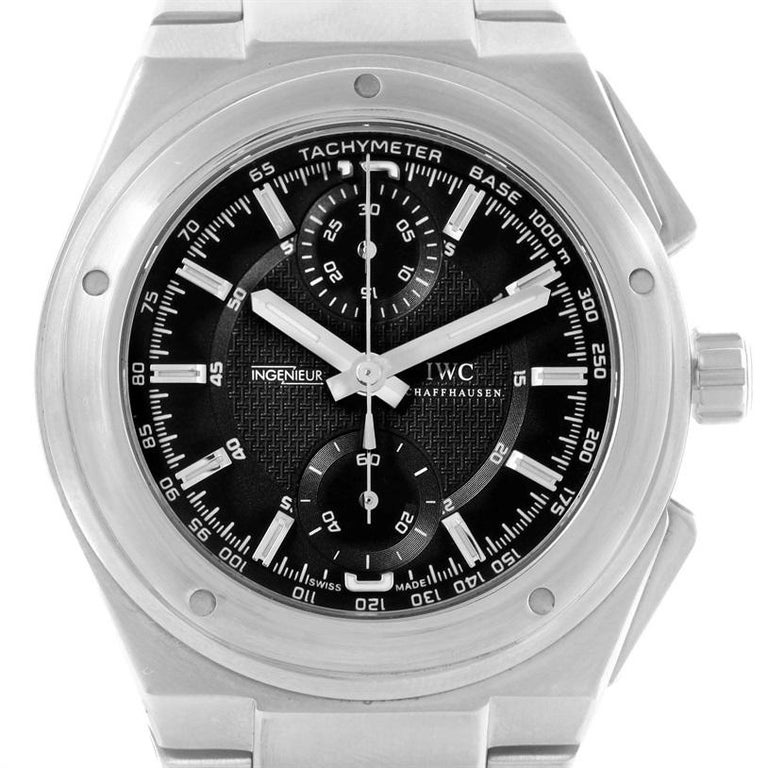

In addition to devising the Royal Oak and the Nautilus during this period, Genta famously redesigned IWC’s Ingenieur in 1976, adding five screws to the bezel in an asymmetrical pattern.

During the 1980s, he created the Bulgari Bulgari, based on a Roman coin, as well as an updated version of the Pasha de Cartier, originally designed in 1931 by Louis Cartier as a one-off for the pasha of Marrakech. Genta reconceived the piece as a luxury sports watch with a round case that distinguished it from other Cartier watches, like the Tank and the Baignoire.

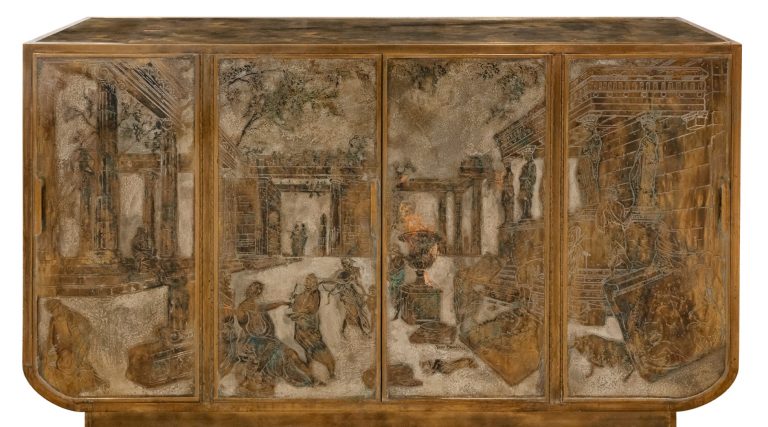

But Genta’s triumphs weren’t limited to his work as a gun for hire. He and his wife formed their own firm in 1969, producing haute timepieces for private clients, who included royalty, like Great Britain’s Queen Mother and the sultans of Brunei and Oman, in addition to business magnates, sports figures and entertainers.

“It was an unusual brand, doing mostly prototypes,” Evelyne Genta recounts. “His passion was creating a new watch every day. He expressed himself as he wanted.”

Many of those expressions involved high complications, the most technically challenging mechanical watch functions. In 1984, at the request of three hunters, Genta made the Gefica Safari. It had a moon-phase complication, which displays the stages of the moon during the 29.5-day lunar cycle, and a compass, and it was housed in a bronze case, because that relatively dull metal would not reflect the sunlight and spook the hunters’ prey.

Genta is generally acknowledged as the first watchmaker to combine a jumping hour complication (in which the hour indicator jumps from one numeral to the next every 60 minutes, instead of changing gradually) and retrograde minutes (where the minute hand moves along an arc and upon reaching the end jumps back to the beginning) on the same dial. But perhaps his most important contribution to high watchmaking was the Grande Sonnerie. Completed in 1995 after five years of research and development, it contained four gongs that emulated the chimes of London’s Big Ben and at the time was the most complicated watch in the world.

Genta had a playful side, too. In the 1980s, he received permission from Disney to create several limited-edition watches featuring its beloved cartoon characters, such as Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck. Produced in 18-karat gold and later also in steel, often with the same high complications as his other models, they’re still some of the most impressive — and expensive — Disney watches ever made.

Even after Bulgari acquired Genta’s firm, in 2000, he continued making watches under the name Gérald Charles. However, despite his enviably long run and the indelible mark he made on every facet of watchmaking, Genta will always be best remembered for popularizing the steel sports watch.

“It is hard to overstate the impact Genta has had in the world of watches,” McKenzie says. “His predominant influence has been in the use of steel as a material and the integrated bracelet, as well as the notion that if you have one watch, you could hardly do better than a great, time-only steel sports watch. We see this now with the Chopard Alpine Eagle, Bulgari Octo Finissimo and Girard-Perregaux Laureato.”

That said, few pretenders can claim the ingenuity or flair of Genta’s biggest hits. “A raft of new watches have taken inspiration from these great designs,” says McKenzie, “but they just don’t have that magic.”