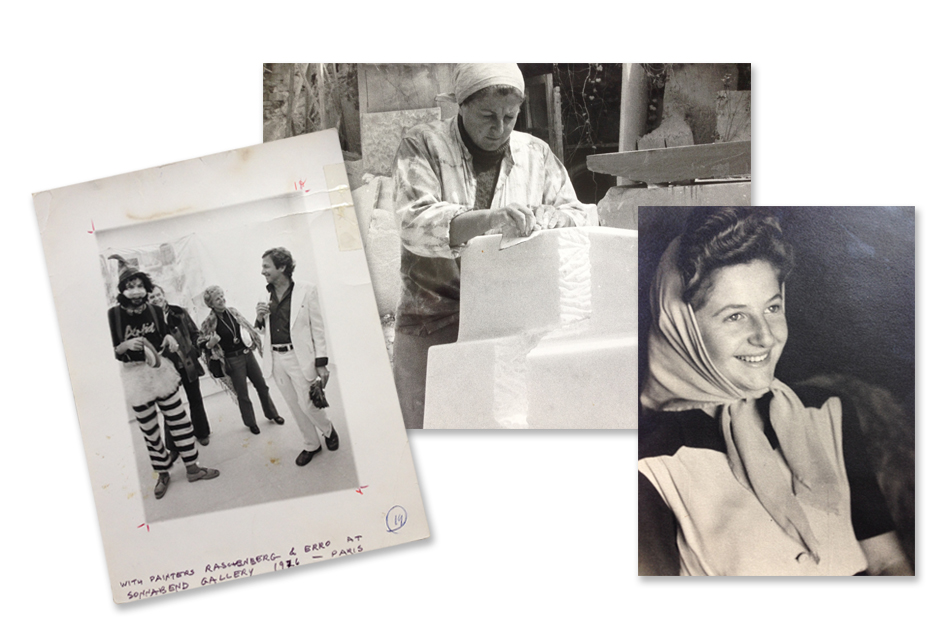

Artist Hanna Eshel in the 1950s with an unknown sculpture (all vintage photos courtesy of Hanna Eshel). Top: Individual marble works reside in a Japanese-style Zen garden of raked sand in Eshel’s NoHo, New York, loft.

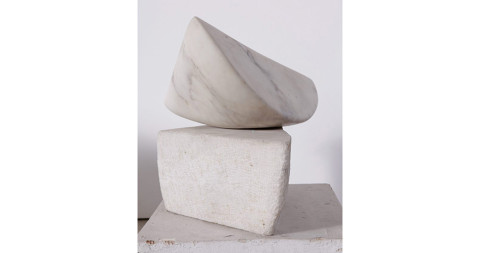

January 8, 2014In 1972, the 46-year-old artist Hanna Eshel left her home in Paris and traveled alone by train to Carrera, Italy, to fulfill a long-held dream of working in its fabled marble quarries. After years of painting, she had become dissatisfied with the limitations of the two-dimensional medium. Her plan was to stay in Carerra for just two months and then move to New York; in the end, she lived there for six years, honing her craft and producing a large body of abstract work that explores dualities of rough and smooth, solid and void, geometric and organic. “I was in love with marble,” says Eshel, who traces her passion for the material back to encounters with Constantin Brancusi’s abstract forms, which to her seemed alive with energy.

When she ultimately made it to New York, she brought with her tens of thousands of pounds worth of sculpture and raw stone that she moved with her into a sixth-floor NoHo loft. So large and heavy were many of the pieces that they had to be hoisted by crane and brought in through one of the space’s 15 windows.

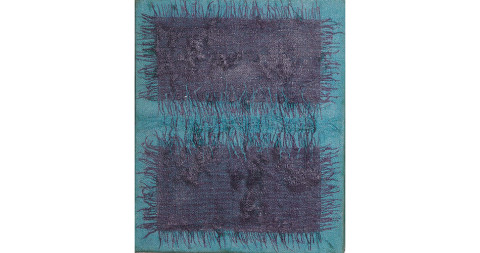

Although Eshel, now 87, had showed regularly in European galleries from the 1950s through the ’70s, and remained active as an artist during her decades in Manhattan, she has never formally exhibited her work in New York. Never, that is, until now: This winter, the New York–based design dealer Todd Merrill is presenting several of Eshel’s large marble pieces, and A-M Gallery is offering a selection of her highly textured paintings on burlap and smaller sculptures through its 1stdibs storefront and at an exhibition hosted by Mondo Cane, in Tribeca, until January 18. “We are thrilled to have the opportunity to shine some light on Hanna’s incredible body of work,” says Justin Luke, partner of A-M Gallery.

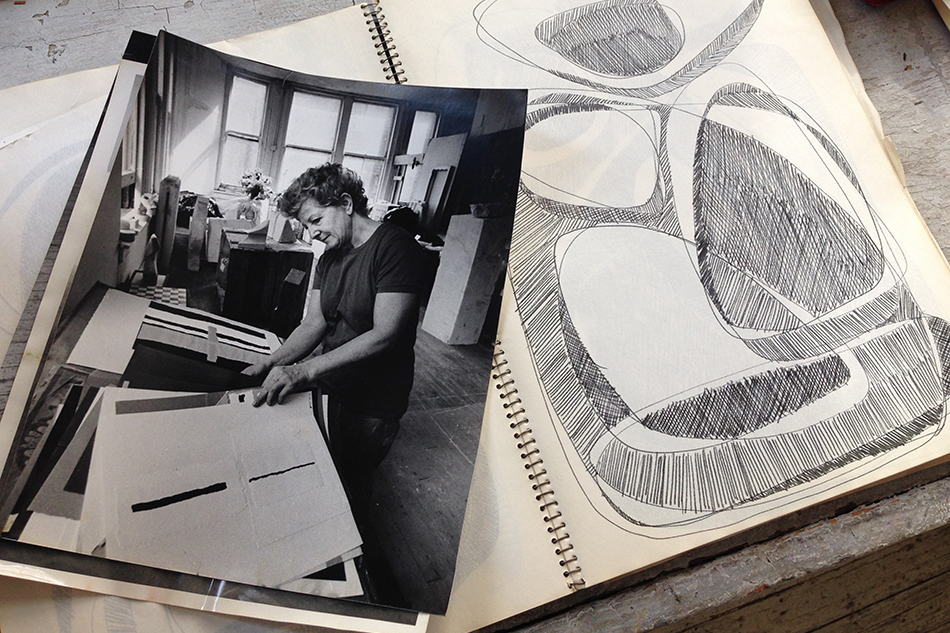

The interior of Eshel’s loft reveals various works on canvas and marble pieces by the artist.

Merrill’s gallery is around the corner from Eshel’s loft, but he only recently encountered the work when a mutual friend brought him by as Eshel was in the process of vacating the space for a nearby assisted-living facility. He knew almost immediately upon crossing the threshold that the work — from expertly carved and polished marbles to a Japanese-style rock garden made with her sculptures to a rich inventory of abstract paintings — had not been produced by a self-taught amateur but by someone well-versed in technique and art history. “Her work is very futuristic and minimalist, while at the same time draws references from ancient civilizations,” says Merrill. “It fits with what was going on in the period.”

“By the time Hanna moved to New York, she wasn’t particularly interested in working the art-world system,” continues Merrill, who has three of Eshel’s large-scale marble sculptures from the ’70s on display at his Bleeker Street gallery. “She’s very serious and highly skilled. The work sells on its own merit and because of its pure beauty, simplicity and the quality of what she did.”

Born in Jerusalem in 1926, Eshel attended the city’s Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design and also served in the Israeli army during the 1948 War of Independence. Breaking with the traditional expectations of her religious family, Eshel moved to Paris in 1952 to study painting at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière and the École des Beaux-Arts. She settled in Paris, married and had a son, all the while making and showing art in Europe with the likes of Galerie Kontakt, in Antwerp; the Monika Beck gallery, in Hamburg; and the pioneering Paris dealer Iris Clert, who first showed Yves Klein’s blue monochromes.

The artist, whom New York gallerist Todd Merrill describes as “pioneering,” is seen here in the 1990s, wearing a necklace of her own design from the mid-1970s.

In the early ’60s, Eshel began making highly textured oil paintings on burlap, some double-sided, with holes, slashes and clefts that suggest bodily openings, cracks in the earth or an existential void. The collaged, relief-like quality of these works became so pronounced that, she says, “I had evolved from a painter to a sculptor, working in three dimensions.” The fissures and cracks in her paintings began to appear in her new sculptural work, and she soon went a step further by splitting the pieces of stone in two. Cracking them open, she says, “gave them a strong, nervous feeling. It seemed that with this trembling line I was expressing a tension that was appearing everywhere.”

Some of those tensions may have been personal — she left Paris for Carerra after the dissolution of her marriage, and she was the only woman in the workshop there among about a dozen other sculptors. In an account of her time in Italy, she writes of her frustration at not being taken seriously because of her sex, but she was undaunted by the challenges: “I kept hammering and chiseling, rasping and polishing, loving and working and feeling the marble until it attained its perfect form.”

These days, as awareness of her work and career grows, Eshel is poised to have the New York career that had previously eluded her. “You realize how pioneering she was, and how strong she is as a personality and an artist,” says Merrill. “It definitely explains the work.”

For her part, Eshel is thrilled about the renewed attention to her work, which she has always hoped would reach a wider audience. “There is a special feeling that starts when I first look at a piece of marble. I can foresee the sculpture that it will become,” she says. “And I re-experience that satisfaction when I see people’s faces light up as they look at a finished work. Their pleasure is my reward.”