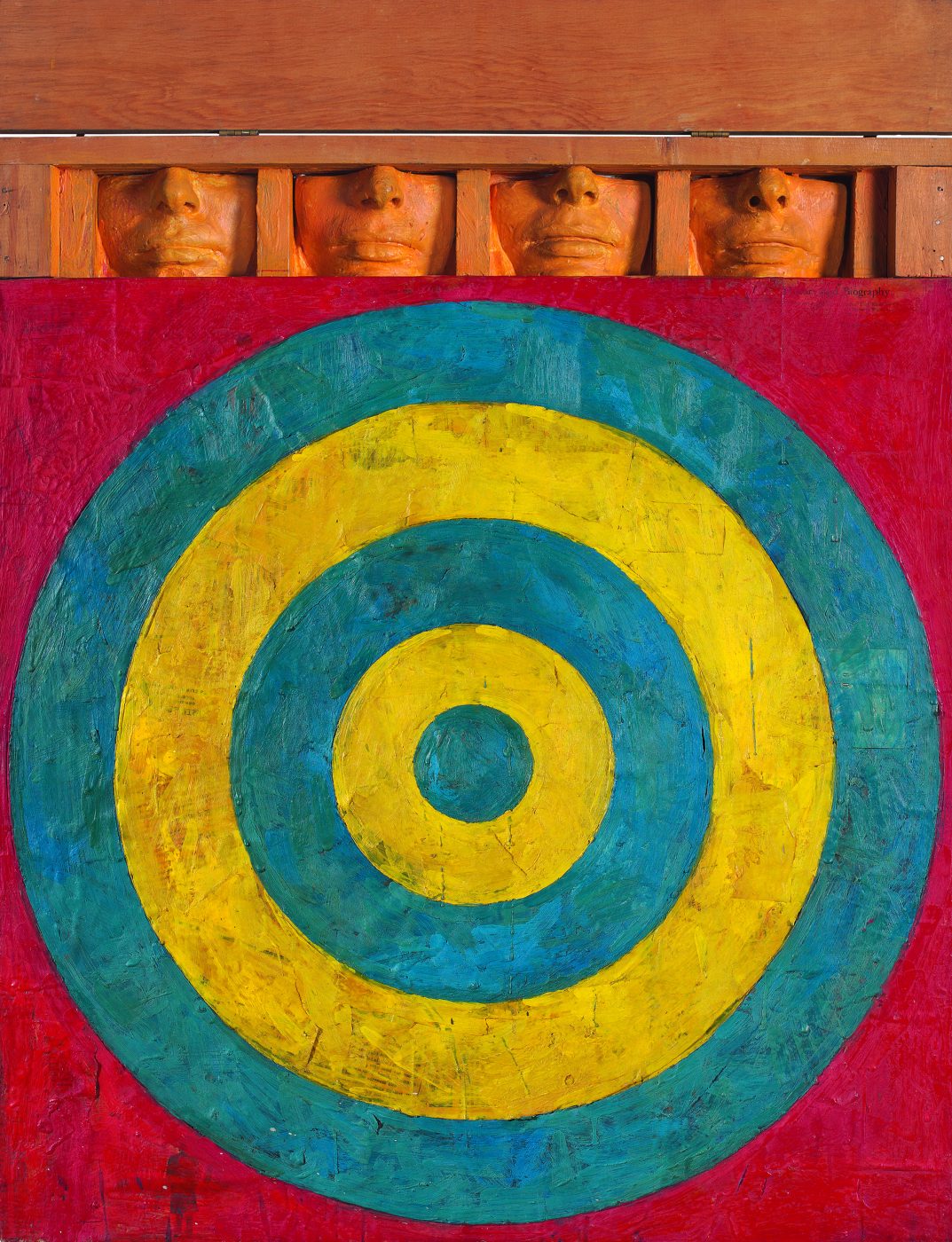

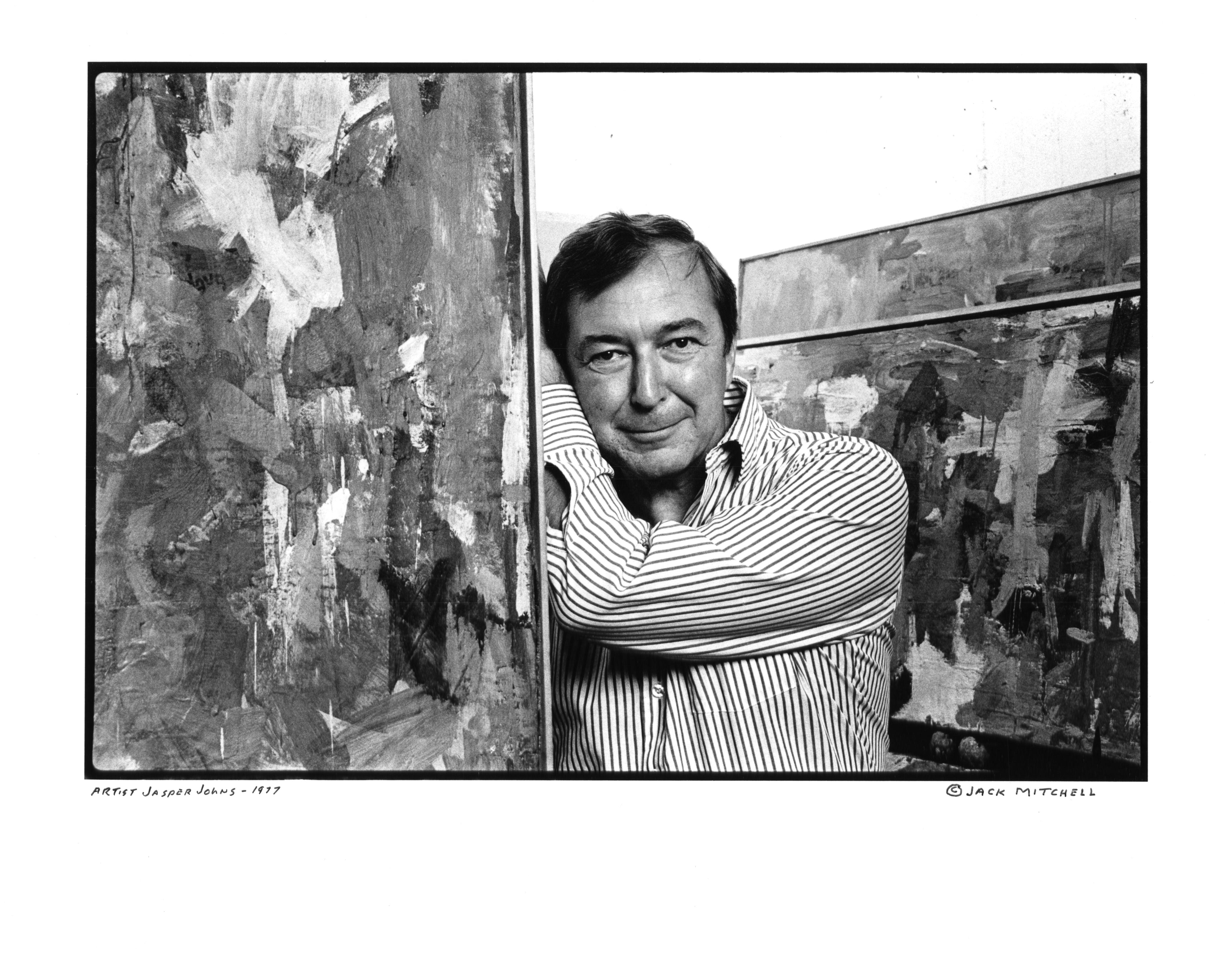

January 9, 2022“Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror” is a stunning two-museum retrospective featuring the artist’s most epoch-defining works, like Flag (1954–55), and Target (1958), plus recent pieces seen publicly here for the first time. The result of a five-year collaboration between Carlos Basualdo, senior curator of contemporary art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Scott Rothkopf, chief curator at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, it was conceived from the get-go as dual exhibitions, mounted simultaneously at the two institutions, that coalesce into one conceptual whole.

In the two venues, viewers are treated to more than 400 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, as well as fascinating mixed-media works dating from 1954 to the present. Many of the shows’ earliest pieces anticipate conceptualism or Pop art and carried forward Duchamp’s legacy at a time when few outside Johns’s circle grasped the dadaist’s impact on the art world.

There’s a conscious symmetry in the selection of the exhibition sites. The galleries in each museum have been designed in a kind of call and response. “We use the idea of doubles, of mirroring and repetition as a generative process in our design, and repetition for Johns was a means of creative exploration and inquiry, not used for its own sake,” Basualdo explains.

“Carlos and I always understood that our unique contexts would inflect the sense of Jasper’s oeuvre,” says Rothkopf. “In Philadelphia, his art would be seen near some of his greatest inspirations and references, including Duchamp, CÉZANNE and PICASSO. And the Whitney is known as a place for contemporary art, like our biennials, so it was important to really show Jasper as a living artist still pushing his work forward after so many years.”

Both exhibitions consider the impact of place. The Philadelphia Museum has an in-depth look at the influence of Japan on Johns’s work during and after his 1964 visit to the country features the artist’s signature cross-hatch pieces, collectively titled “Usuyuki,” a Japanese word meaning “light snow,” which for Johns evokes the transitory nature of beauty. The Whitney’s presentation of Johns’s “Numbers” series, created at Edisto Island in North Carolina, provokes a deeper understanding of the artist’s use of numerals as both painterly gestures and symbols.

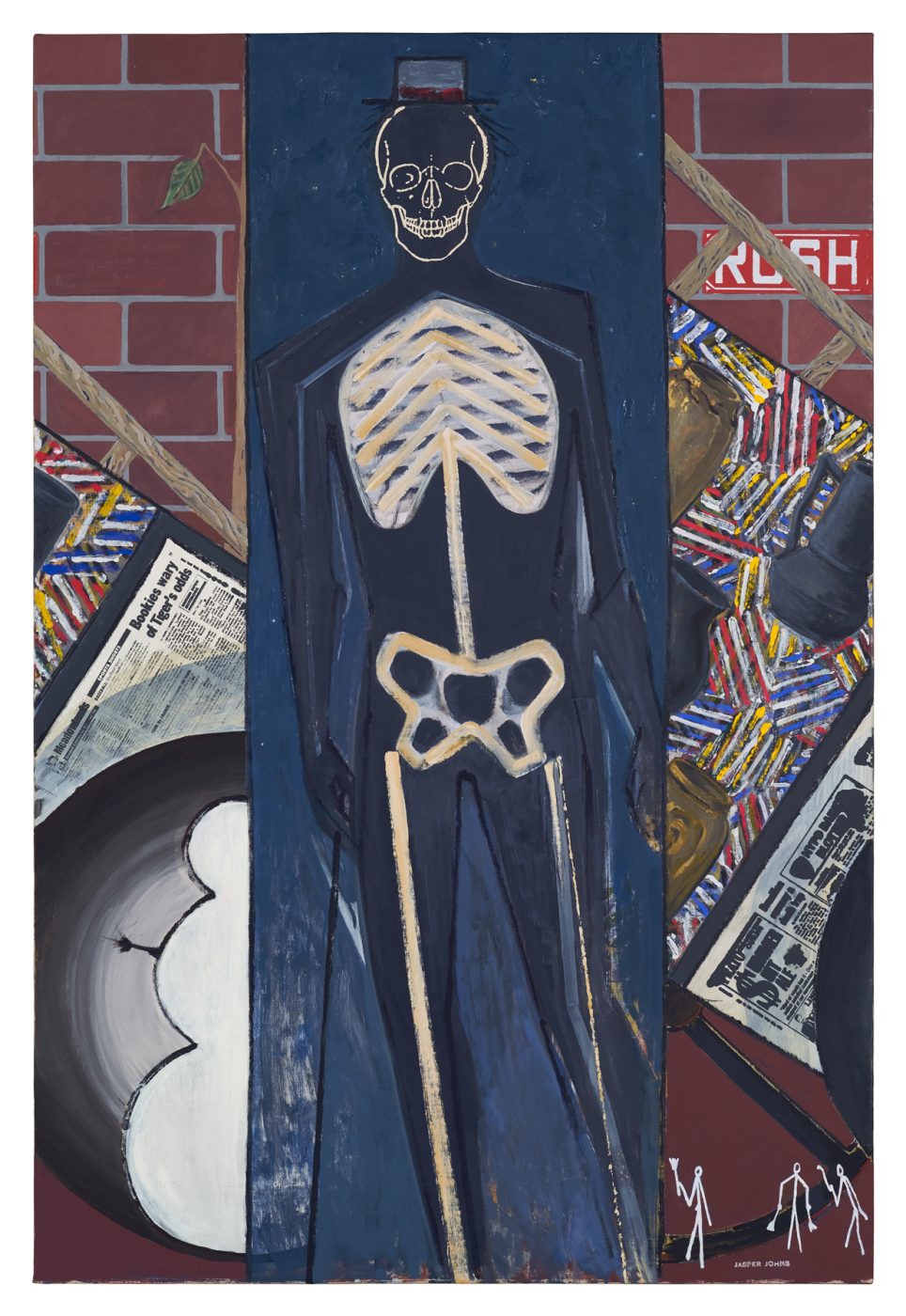

If you did not know it was a Johns show, you might not recognize some of the pieces on display as his — rare, fascinating works that contain spindly, shadowy figures, apparently ruminations on the body and mortality. “The body figures prominently, but not as content. It is there to remind us that making the work is a strenuously physical process,” Basualdo says. “Even in the ‘Numbers,’ which seem intellectual, there is the over-and-over-marking quality that suggests a repeating gesture, a kind of choreography.”

The revelation here is the inventive energy and courage of this artist, who, through nearly 70 years of art making, moves past what we expect and what was demanded in his day. In the early 1960s, when race tensions at home and war in East Asia tested the American white-cis dream, Johns was a gay man who dared make replicas of Old Glory.

Created at the height of AbEx’s monopoly on “real” feelings and in the face of conceptualism’s demand for cool remove, Johns’s targets and maps demonstrate the expressive force of flatness and show how abstract forms and banal symbols and objects — letters of the alphabet, beer cans — as well as spaces filled with nothing can join together to create intensely private communication. The Philadelphia Museum’s display of the book on which Johns collaborated with playwright Samuel Beckett — two fellow probers into the nature of language — is an epiphany.

“Johns’s art of nineteen fifties and sixties was radical and disruptive, but he also remained true to certain traditional formats and values, such as easel painting and even the handmade,” says Rothkopf. “His work paved the way for artists like Richard Serra or Eva Hesse to explode conventions further, while he continued to innovate from within.”

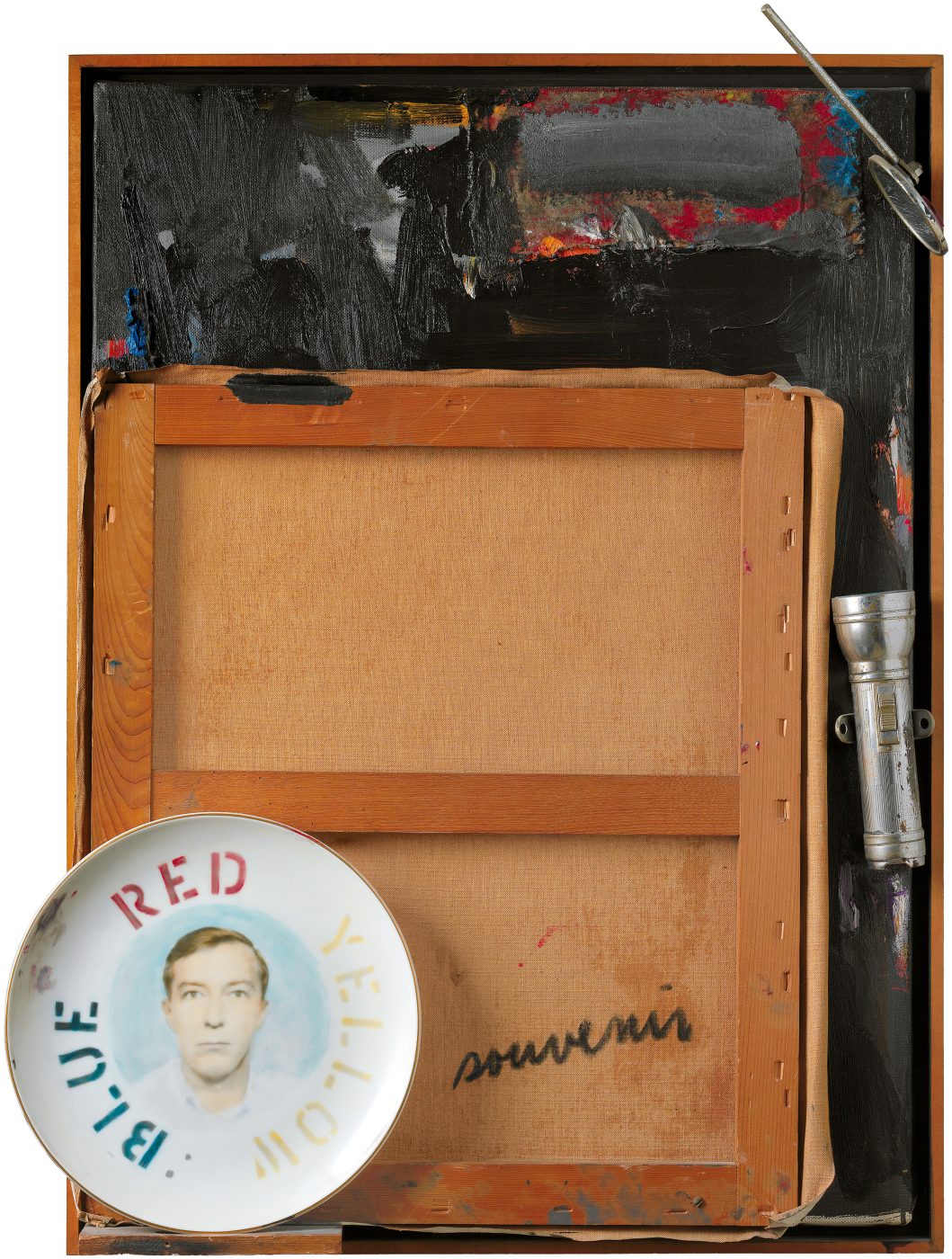

It is amusing to recall that as late as the 1980s, college textbooks on art quaintly referred to Johns and like-minded innovator Robert Rauschenberg as “close friends.” The two artists were lovers for half a decade and lifelong collaborators who, along with couple Merce Cunningham and John Cage, formed a nexus of discreetly queer artists pioneering what we’ve come to term postmodernism, in which painting mirrored sculpture, image echoed text, ideas became actions, people loved whom they loved, and art could be anything: a danced shape, a flashlight affixed near an old photo or a painting of a common flag.

These currents and arcs are beautifully delineated in both shows.