Juan Montoya, who has homes in New York, Paris and Bogotá and the Hudson River Valley, has learned five languages so that he can communicate with his clients in their native tongues (portrait by Ron Reeves). Top: For a family vacation home in the Dominican Republic, Montoya designed an outdoor living room with coral stone flooring, custom furniture and waterfront views. All photos by Eric Piasecki, unless otherwise noted

February 6, 2017Juan Montoya has every right to rest on his laurels. Although he won’t reveal his age (“Youth is in the eye of the beholder,” he says with a mischievous smile), some sleuthing indicates he’s firmly established in his seventh decade on this earth. Montoya’s achievements during that time are legion. He has a prodigiously successful interior design business, countless awards (Interior Design Hall of Fame inductee, regular appearances on the AD100 list, Legends Award from Pratt), three monographs, regular speaking engagements and constant international travel.

Yet Montoya’s view of this impressive résumé is characteristically humble and open-ended. “I’m a spiritual person,” he says. “When I get stuck, I realize that life is in a state of constant evolution. As the Buddha would say, ‘The world is in continuous flux, impermanent.’ I perceive life as a learning process.”

That process began for Montoya in his native Bogotá, Colombia, as the son of a diplomat who also owned a rice farm in the countryside. Moving between these homes inculcated in him both a love of fine things — he lived amid Louis XV and XVI furniture in the city — and nature. To this day, he is athletic, enjoying jogging, tennis, swimming and walking. “Being outdoors is very important to me,” says Montoya, who is also an avid gardener.

Montoya’s mother hails from an illustriously creative family: Her grandfather Jorge Isaacs Ferrer wrote María, acknowledged as one of the most important works of 19th-century Latin American literature. Montoya’s paternal grandfather was a painter. “My parents,” he says, “valued education and politeness.” One need only observe his impeccable manners to see their influence.

A dramatic rice-paper and bamboo light fixture hangs in the master bedroom of the Dominican Republic retreat. A teak bench from Andrianna Shamaris is positioned at the foot of the bed. The headboard and doors were custom designed by Montoya.

As a boy, he painted in oils and watercolors and, he recalls, “made little houses out of cardboard, painted them and gave them as gifts.” His three years of architecture school in Bogotá, therefore, did not come as a surprise to anyone. In his early 20s, he arrived in New York to attend Parsons School of Design, living with an aunt in Queens and graduating with a degree in environmental design in 1972. From there, he decamped to Europe, where he worked in Paris and Italy for a time before returning to Manhattan and establishing his own firm in his Abingdon Square apartment in 1978.

Although he is consummately fluent in many styles — citing Art Deco, Bauhaus, Brutalism and Swedish design as particular inspirations — Montoya has developed certain recognizable hallmarks over the course of his nearly 40 years in the business. He places great importance on “a sense of arrival,” expending considerable thought on entries, from which he immediately establishes clear axes to lead the eye naturally from one space to the next. He greatly respects the relationship between architecture and interiors. That could mean creating a more intimate communion with art at a harshly industrial, white-box Parisian art gallery by painting walls gray and devising movable partitions. Or designing a headboard sporting Aztec motifs for a stone-and-thatch resort residence in Mexico. Or creating coffers, pilasters and moldings that both disguise a Manhattan pied-à-terre’s low ceilings and provide a more sophisticated envelope to showcase Deco-inspired furnishings.

“When I get stuck, I realize that life is in a state of constant evolution. I perceive life as a learning process.”

The wood-paneling-clad bathroom of this Whitefish, Montana, fishing lodge features a tub and bench from Ann Sacks and ceiling lights from Urban Archeology.

Incorporating his love of travel, Montoya’s rooms often bring together erudite assemblages of art and objects from many eras and cultures, which he usually sets against soothing neutral palettes and sensual mixes of textures that allow these tableaux to shine. He also believes in orientation to place. So, for example, his design for a lakeside home may include canoes suspended from a rustic beamed ceiling, while a New York Deco-style apartment might sport floral bas relief walls riffing on Lalique motifs that historically would have been executed in glass. And he is an avid fan of the bold impact statement, frequently including striking abstract art and overscaled objects that impart drama to a space (witness his 2014 Kips Bay salon, which featured an enormous contemporary custom sofa under a gargantuan 18th-century chandelier).

Is there anything Montoya has done that he would not repeat? The channeled leather beds and mauve palettes of the 1980s for instance? “No, nothing,” he says. “It all blends, like a weaving where all elements form part of a whole.”

“You would probably never paint a room salmon again,” quips Urban Karlsson, Montoya’s Swedish-born companion, whom he met in Paris in 2000.

“Well, I would never have painted it salmon unless the client had requested it in the first place!” Montoya laughs.

The two divide their time among various residences, which include their home base, an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. La Formentera, their country home, an hour north in Garrison, New York, was lavishly illustrated in a 2012 monograph of the same name. A pied- à-terre in an 18th-century apartment building on Rue Jacob in Paris’s 6th arrondissement serves, Montoya says, as an “excellent stepping point” for European shopping trips. And an apartment with multiple balconies overlooking the city in Bogotá’s tony Rosales neighborhood allows the designer to be close to family.

A large artwork by Aaron Young hangs in the living room of this Southampton home, which contains a Liza Sherman chandelier and a pair of Patrick Naggar sofas.

Today, Montoya employs between 8 and 10 staffers and juggles five or six projects at a time. The firm’s current focus is on a 20,000-square-foot condominium in Miami and an expansive apartment on New York’s Fifth Avenue. But client calls take Montoya all over the world, including France, Spain, the Dominican Republic, Russia, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina and Panama. Fortunately for him, he speaks five languages. “I don’t want to get lost in translation!” he exclaims. “I learn languages so that I can convey concepts with clients in their native tongue.”

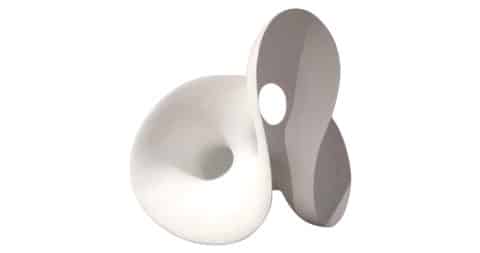

That would be an abundantly full life for most anyone. But Montoya remains restlessly creative. “I love new materials and the complexity and versatility of what can be done with them,” he says. He also continues to make art, nowadays concentrating mostly on abstract geometric stone and metal sculpture. “I love geometry. Barnett Newman had a lot to do with it,” he says, referring to one of his early idols, “and Victor Vasarely. At Parsons, I studied with a pupil of Vasarely’s and also a student of Josef Albers. They taught me about form, shape and color.” During his post-college Paris days, he remembers, “I also had the opportunity to live in a studio once owned by Juan Gris. It had no bathroom or kitchen, but there was lots of natural light and chairs Gris had hung on the wall to clear enough space to paint. That’s where I started painting again.” He has never let up.

In addition to his furniture designs for Century (he was selected to create the furniture company’s first Icon collection in 2010) and rugs for Stark Carpet, this year Montoya released a seven-piece collection of furnishings for Biasi & Co, as well as hardware designs for P.E. Guerin and Pivot. And, he says, “I’m always on the lookout for unique projects — perhaps a church? Or maybe a hospitality project that helps people, such as a retirement or assisted living community for older people. I think it’s important to give back.” Not that he hasn’t already done just that. Montoya has for many years supported Colombian charities for elder living and been actively involved with Aid for AIDS, among other organizations.

It is all part of a lifelong journey for Montoya. What is the reward at the end of this process? “What makes me happiest is being able to make people smile,” he says.