September 22, 2019This fall, at the New York School of Interior Design on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, you can be among the first members of the public ever to get a glimpse of the colossal archive of historic textiles amassed by Kravet, Inc., the 101-year-old leader in to-the-trade textiles for the home furnishings and hospitality industries.

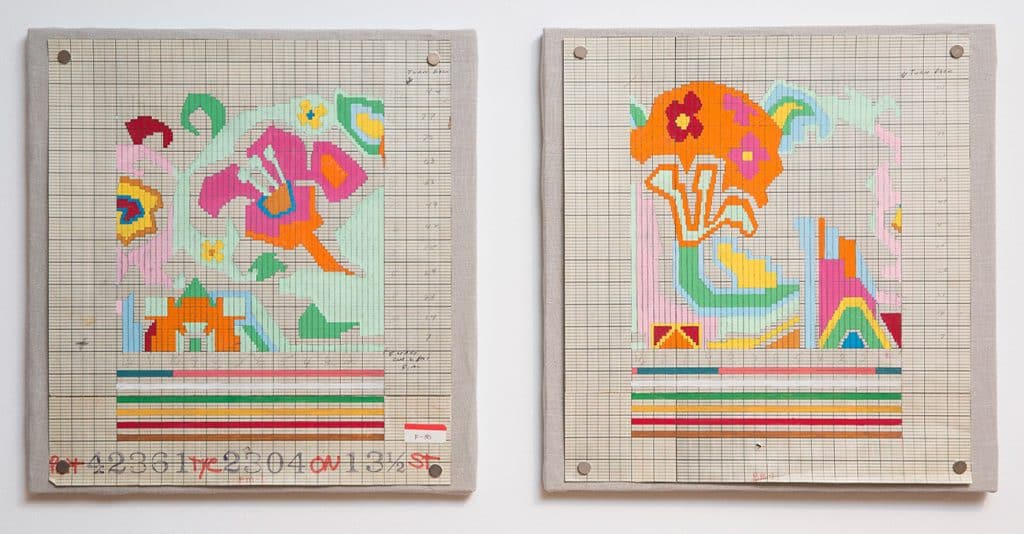

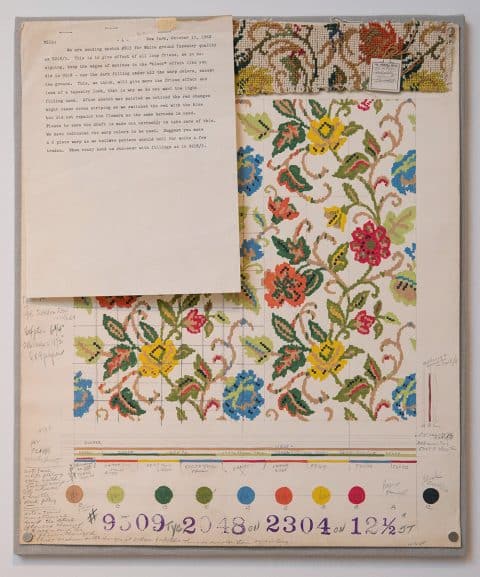

A new show devoted to historic textiles collected by the 100-plus-year-old furnishings company Kravet, Inc., “Pattern and Process: Selections from the Kravet Archive” is up through November 27 at the New York School of Interior Design, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. The exhibit includes a 19th-century collaged sketch page for fabric from the French company Moreau & Deminière (left) and a textile design made in the 1920s or 1930s. All photos by Matthew Carasella

The 80 primo examples in “Pattern and Process: Selections from the Kravet Archive,” which runs through November 27, range from a fragment of an ancient printed Egyptian cotton to a 19th-century Kashmiri paisley shawl and 1960s Pop florals. These are juxtaposed with contemporary fabrics and wallcoverings conjured from them by Kravet’s bevy of talented designers.

“The show is incredibly diverse, inspiring thoughts of how we can incorporate colors, patterns and weaving techniques from every period of history and every country of origin into today’s interiors,” says Manhattan interior designer David Scott, who graduated from NYSID in 1991 and now serves on its board of trustees.

This 19th-century Kashmiri paisley shawl features embroidered twill tapestry.

The items displayed in the NYSID exhibition represent just a fraction of Kravet’s vast holdings. The company, which includes such luxury brands as Lee Jofa, GP & J Baker and Brunschwig & Fils, possesses a gargantuan collection of fabrics and related artifacts that is 60,000 pieces strong and growing. This extraordinary repository is largely the work of chief creative director Scott Kravet, a fourth-generation manager of a business that, despite its 43 worldwide showrooms and 1,100 employees, has remained very much a family affair. “Why have an archive, if you don’t share it?” he says, explaining the motivation behind the show.

Scott’s enthusiasm is infectious. When we met earlier this month, he had recently returned from a whirlwind trip including a visit to a defunct fabric mill on the Belgian-French border that he calls “the best three days of my life.” His indefatigable hunt for antique materials, which the company’s designers often use as springboards to produce multiple yearly collections, has earned him the nickname “the Indiana Jones of textiles.”

In the near-rubble of the abandoned European factory, among the ghostly silhouettes of old looms and wooden warpers, he discovered some 3,500 enormous portfolios of late-19th- and early-20th-century fabric. “It takes two people to carry each one,” he says. They were filled with original ink and gouache drawings known as mises en carte, or point papers. Motifs included Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau florals, Art Deco butterflies, Bauhaus geometrics, Jacobean– and Tudor-inspired designs and chinoiserie patterns, all in endless color variations.

Another Southasian piece, this one from the early 20th century, depicts the Hindu god Krishna.

“It’s a massive archive to move and store,” says Scott, who, when the deal is finalized to acquire the archive, will need to make room in the climate-controlled storage facility at the company’s corporate headquarters in Bethpage, New York. There, the portfolios will join materials inherited when Kravet purchased the storied, nearly 130-year-old Brunschwig & Fils in 2011, as well as Kravet’s own designs.

The Nympheus pattern from Lee Jofa – a nearly 200-year-old brand owned by Kravet since 1995 — covers a stool in the show.

All is meticulously organized by year and season. “When the Brunschwig team imagines a new collection, they go back to the classics,” Scott says. This year’s crop of fabric and wallpaper offerings, for instance, includes one of Brunschwig’s signature patterns, Les Touches, a stylized animal print from the mid-20th century, in nine brand-new colorways.

On another recent trip, Scott found himself in the Lake Como home of an antique textiles dealer from whom he has previously bought hand-painted Persian prints and other rare treasures. The seller showed him a number of items and told him he’d seen everything, but Scott wasn’t having it. “What are those pieces in the corner?” he asked, gesturing to some tall rolls propped against a wall.

They turned out to be the original 1920s art for a woven tapestry, lushly colored scenes of a Middle Eastern souk complete with palm trees, camels and domed temples. These now repose in the company’s Manhattan design studio, on West 21st Street, along with an antique Japanese kimono found at a vintage clothing fair in London and rough mulberry-bark cloth from the South Pacific. The 1960s floral in the NYSID show is part of a 10,000-piece haul of original artwork that Scott acquired for the company from the now-closed Orinoka Mills, in Pennsylvania.

Among the 10,000 pieces of original artwork Kravet acquired from the now-closed Orinoka Mills, in Pennsylvania, are these point paper drawings for 1960s floral patterns.

“You never know where inspiration will come from,” Scott says.

The busy 21st Street studio, where phalanxes of designers work at room-size tables and on giant computer screens on two floors of a vintage loft building, feels a long way from the company’s origins.

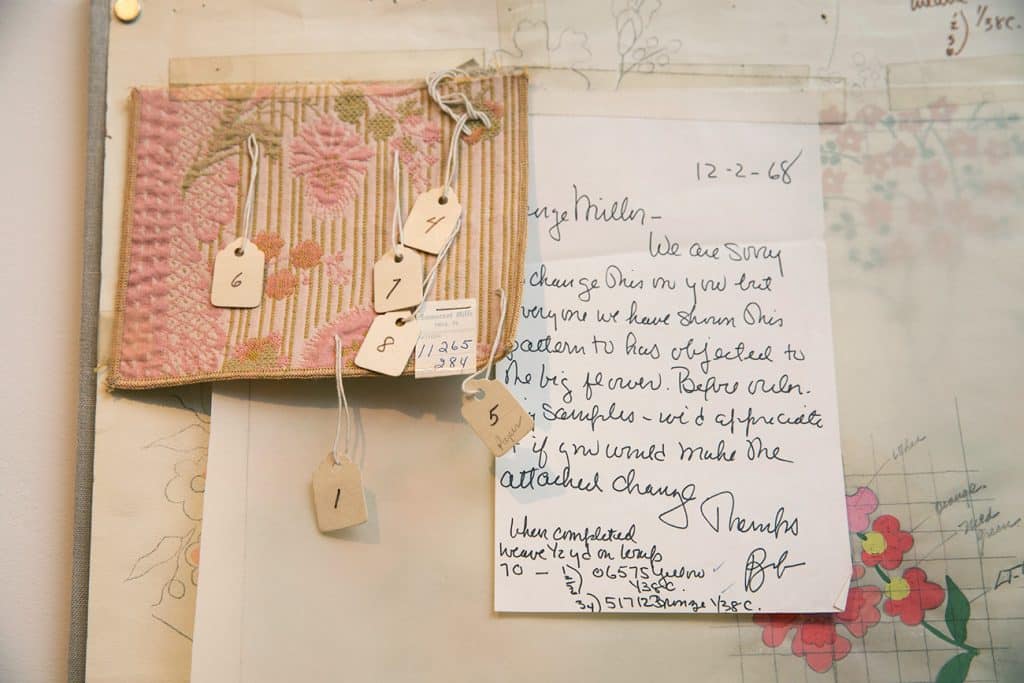

This point paper drawing depicts another floral pattern from Orinoka Mills. A note attached contains weaving instructions from the designer for the mill, specifying warp, density and repeat.

It’s a classic Jewish immigrant story, which began in 1903 when Sam Kravet, Scott’s great-grandfather, arrived from Russia with “nothing but the clothes on his back and a sewing machine,” he says. After stints in Ottawa and Detroit, Sam settled on New York’s Lower East Side and opened a tailor shop. “Guys would arrive for fittings in chauffeured cars,” Scott says, and Sam would travel uptown to their posh brownstones and mansions to deliver the finished goods. “He saw the way they lived, and he would say, ‘You could use a tieback on those drapes in the parlor or a rosette for those picture frames.’” From that, Sam launched into passementerie, selling tiebacks, corded rope, notions and trimmings from a storefront on Norfolk Street, opened in 1918.

Sam Kravet had four sons. “Whoever lived the longest inherited the company,” Scott says. And so it went, with members of subsequent generations, including Scott’s late father, Larry, shepherding the firm through the interior design industry’s exponential growth following World War II. Scott and his two siblings, Cary Kravet and Ellen Kravet, as well as Cary’s wife, Lisa, all joined the business in the 1980s. A fifth generation, including Sara and Sander, Cary and Lisa’s two children, and Scott’s son Daniel, have entered the ranks in recent years.

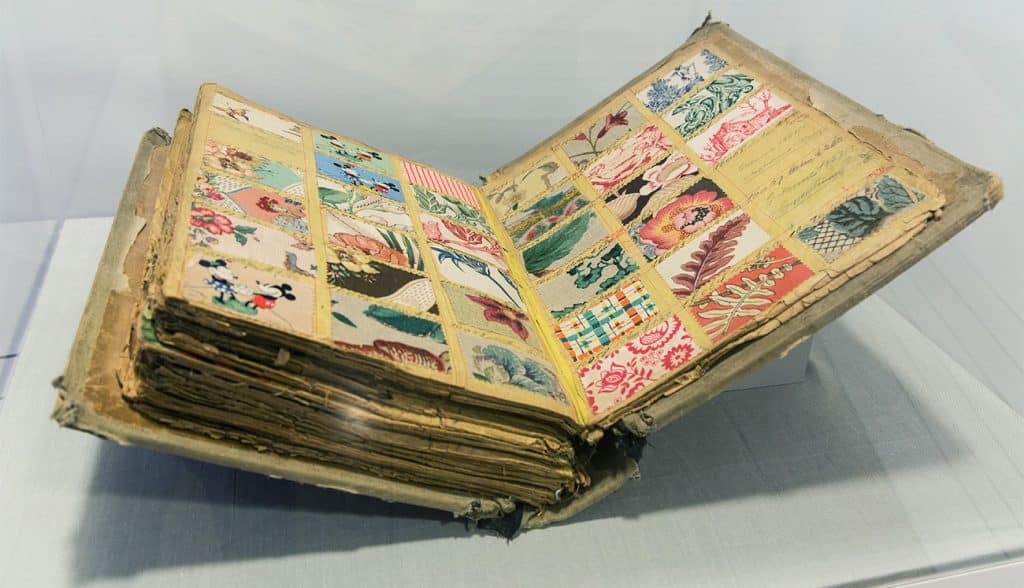

Design collages and fabric samples from the 1930s through the early 1940s fill a bound ledger from the archives of the British textile company GP&J Baker.

It was Ellen Kravet, as chairman of the board at NYSID, who conceived the idea for the current exhibition while giving board members a tour of the archives in Bethpage. To curate the display, she brought in exhibition-design studio Darling Green.

If Kravet is masterful in mining the past, it is also forward-thinking, bent on cultivating relationships with the next generation of talented designers. Sharing its archive via the NYSID show dovetails with the company’s efforts to interest future design stars in the field of home-furnishing textiles.

The materials from Orinoka Mills also include this point paper drawing of pink and green flowers, with attached production notes, color reference and a swatch, all from 1968.

Meanwhile, Scott Kravet is planning his next European trip, which will include touring the archives of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, Kew Gardens and a private British collection, as well as Vanoutryve, a Belgian mill with a rich history.

All of which raises the question: Is there a Kravet Museum of Global Textiles in the works? Not at the moment, Scott says. Right now, he’s having too much fun traveling the world.