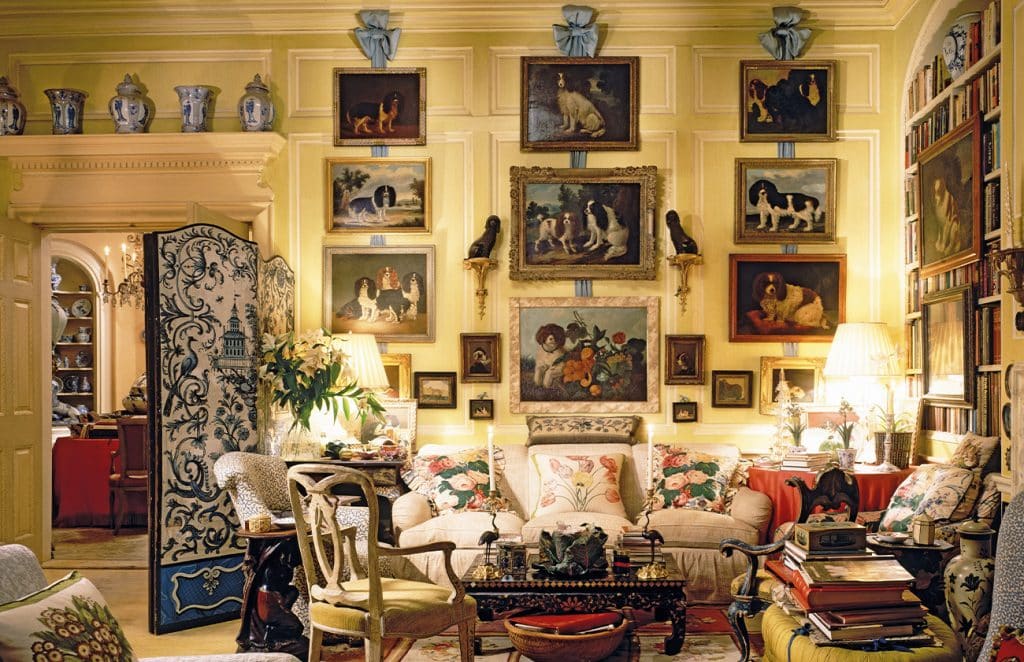

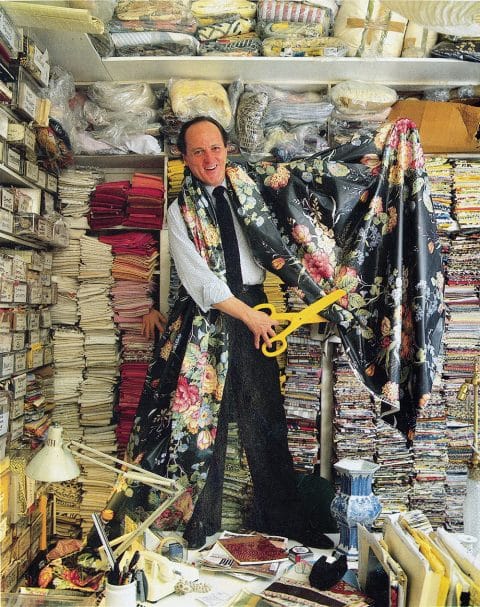

March 15, 2020Mario Buatta, known as the Prince of Chintz, in his sample room. This oversize pair of yellow scissors (along with a set of book spines) sold for more than three times their estimate. Photo by George Lange. Top: For the auction, Rush Jenkins re-created Buatta’s Manhattan apartment at Sotheby’s, even taking a color wheel to the late designer’s home to match the paint. All photos by Gabby Jones unless otherwise noted

Mario Buatta lives. The New York decorator, whose fondness for floral fabrics earned him the nickname Prince of Chintz, died in October 2018 at the age of 82, but his spirit returned with a vengeance in January, when the Sotheby’s sale of Buatta’s personal collection succeeded beyond anyone’s imaginings, fetching two and a half times its presale estimate. What’s more, the weeklong sale preview became a glittering event on New York’s midwinter social calendar.

Even Emily Eerdmans, the design historian who coauthored the definitive Buatta monograph, 2013’s Mario Buatta: Fifty Years of American Interior Decoration, and was hired by his estate to oversee the sale of all manner of antiques from his Manhattan and Connecticut homes, was amazed by the response. Buatta was a household name in the 1980s and ’90s, known for his English-country-house-gone-mad style and an illustrious clientele that included Henry Ford II; Barbara Walters; publishing giants Malcolm Forbes, S.I. Newhouse Jr. and Nelson Doubleday; and entertainment figures like Mariah Carey and Billy Joel. In recent years, however, his star had faded, and he was little-known among the younger set. Still, millennials came out in droves for the Sotheby’s preview. “This was one of the first social-media-era style-maker auctions. It’s so hard to get people out, but I was astonished by the number who not only came to the preview but are still talking about it,” Eerdmans says. “Mario would be thrilled that people are celebrating his joyous, beautiful, layered rooms.”

The 922 lots included such rare furnishings as a circa 1730 black-and-gold-lacquer bureau from China, which brought $152,500 against an estimate of $50,000 to $80,000; and a 19th-century Gothic-style lacquer canopy bed, which sold for $43,750, nearly quadruple its $8,000-to-$12,000 estimate. Also on offer were two dozen dinner and dessert services, more than 50 dog paintings (mostly spaniels) and an array of gilded door knockers, porcelain vegetables, penwork objects, Chinese export porcelain and other decorative pieces. After 22 hours of mostly online bidding, with some people staying up all night to place telephone bids, Buatta’s trove had fetched an astounding $7.6 million. The question in many people’s minds is why. “A lot of what Mario had was so out of style,” says New York interior designer Thomas Jayne, whose own work skews traditional. “Is there now going to be a cascade of people putting bow knots over their paintings? Bow knots in Bushwick?”

Flanked here by a pair of Chinese-style glazed-earthenware models of pagodas, this ca. 1730 Chinese export black-and-gold-lacquer bureau cabinet was previously sold at Sotheby’s in 1983.

Maybe so. At the preview preceding the January 23-to-24 auction, people got the full-bore Buatta experience via a simulacrum of his florid style created by Rush Jenkins. The Jackson Hole, Wyoming, interior designer and former director of design at Sotheby’s has masterminded some 60 presale exhibitions for the house in the past 17 years, including the ones for the estates of Bill Blass, Katherine Hepburn and Johnny Cash and for the personal jewelry collection of Bunny Mellon, the philanthropist, horticulturalist and art collector. For the Buatta preview, he transformed the concrete floors and cement pillars of Sotheby’s ultracontemporary Upper East Side space into a convincing replica of the late designer’s Manhattan apartment, which contained one of the most iconic living rooms of the late 20th century, where rows of dog paintings hung from giant blue bows against pineapple-yellow walls. “We took a color wheel to Buatta’s residence and matched the wall colors exactly,” Jenkins says. “We created a classical architectural backdrop, complete with crown and base moldings, then fastened scrims printed with twenty-by-ten-foot images of Buatta’s interiors to sheetrock panels, overlaying them with actual objects and paintings and furniture. We wanted to make it as authentic as possible, so people could feel they had stepped into the life of Mario Buatta. It was important for that to come through.”

A George III giltwood and carton-pierre mirror hangs above a Louis XVI–style white-painted console with a marble top, which is adorned with a pair of painted-tole graduating plant stands and a Staffordshire pearlware bust of Caroline of Brunswick, queen consort of the United Kingdom.

It did. Millennials reared on a diet of mid-century modern created buzz for the sale by posing next to a cut-out figure of Buatta and sharing the photos on Instagram. “Young people have only known simple and austere,” says David Kaihoi, a partner with Miles Redd in the Manhattan design firm Redd Kaihoi, who, during his initial four years in New York after leaving Minnesota two decades ago, worked on and off with Buatta as a fine-art installer. “Bows and chintz and maximal layering is something they are experiencing for the first time. They haven’t rejected it yet.” Kaihoi thinks the celebratory sale “planted a seed” in the minds of young decorators and designers. “Now they have a context for Mario’s sensibility and vernacular. They’ve seen the stuff, touched it, personally related to it, saw the public rally around it, and now it’s going to be a part of their language.” Designer Sasha Bikoff, 32, whose too-much-is-never-enough ethos is similar to Buatta’s, cited him as an influence in a recent interview with Architectural Digest. Another young fan, the 37-year-old designer Nick Olsen uses antiques liberally, much as Buatta did, never shying from bold color, pattern or an overscale gesture. “I’ve been a proud chintz-loving fan of Mario’s since childhood, met him several times and once sat next to him at a dinner party. I always admired his color sense and perfectionism and the humor that came through in his rooms,” says Olsen, who bid on an 18th-century polychrome and giltwood Venetian Rococo child’s chair that sat in Buatta’s own living room and eventually sold for $8,125. “I wanted it desperately. The chair has exceptional personality, and I would have paid three thousand or four thousand dollars, but I was quickly blown out of the water and left empty-handed.”

Not everyone shares this view of the sale’s success. To Bunny Williams, the renowned interior designer whom the New York Times has called “the doyenne of cozy chic,” the celebrity element was a chief factor, along with what she calls “auction fever.” “Obviously, there were people who wanted a part of Mario,” Williams says. “But there were a lot of things — china, candlesticks, lacquer tables, Staffordshire dogs — dealers are having a hard time selling out of their shops today. It was interesting that there were that many people willing to spend that much money on things for which there doesn’t seem to be a big demand.” Williams bought a few pieces for clients and coveted an early 20th-century still-life painting of a head of cabbage for herself. (Vegetables were a theme for Buatta; the sale also contained numerous porcelain cabbages and a 107-piece set of modern Dodie Thayer pottery Lettuce ware that shocked everyone by bringing $60,000 against an estimate of $10,000 to $15,000). “Do I think in six months you’re going to see swagged-bow pictures and chintz curtains? No. But what I’m hoping is that people are becoming interested in buying objects again, and realizing how important they are in giving personality to a home or a project.”

Stair auction galleries in Hudson, New York, just held a second sale of Buatta’s possessions, gleaned from his multiple storage units as well as from his homes. The average high estimate was about $900, as opposed to about $3,000 at Sotheby’s. Left: At Stair, a Regency giltwood and ebonized four-light girandole mirror hangs over a neo-Gothic provincial painted console table. Right: The auction featured plenty of still-life and portrait paintings, especially ones of dogs. Photos courtesy of Stair

Jayne, whose most recent book, Classical Principles of Modern Design (Monacelli), is a modern take on the work of Edith Wharton, the early-20th-century writer and decorator famed both for her landmark novels and for The Decoration of Houses, an early guide to interior design, likewise sees no signs of over-the-top traditional decorating coming back into vogue. “It’s more a matter of true believers in traditional having an opportunity to buy at the well,” says the designer, who purchased a set of nine blue-and-white Chinese Qing dynasty vases for clients. “With Mario, there was a level of connoisseurship, but the sale was also generally about people wanting souvenirs. I wouldn’t say you could use the values from that auction as fair market value. Staffordshire dogs, for example, are a category where you can find myriad examples for less money than people paid at Mario’s sale. A few Staffordshire dogs go a long way.”

At the same time, Jayne believes the sale did well because “it was full of things that are classic — as Edith Wharton put it, ‘because of a certain eternal and irrepressible freshness.’ Mario employed Anglo-American classics. His idiom has stood the test of time.”

An array of porcelain figures ranging in shape from cabbages to tulips fills a George III red-japanned bureau. A 19th-century Continental canine-form walnut child’s chair sits next to one of a pair of gilt and ebonized-wood dolphin-form jardinieres.

On that point, Kaihoi would agree. “Mario was very good at being light and joyful, but he was also an American master with very sophisticated taste,” he says. “Compared with other sales with fanfare and celebrity, people aren’t only going to pay for a story. People bought the scissors and other cheeky moments [a pair of yellow plastic scissors and some ersatz antique book spines sold for $1,635 against an estimate of $300 to $500], but the numbers of the sale were elevated because the furniture was real. These things really were what they were.”

For those not satiated by the Sotheby’s event, more of Buatta’s possessions, gleaned from his multiple storage units as well as from his homes, went on the block at the Stair auction galleries in Hudson, New York, on March 13 and 14. (And there will be yet more Buatta ceramics and objects on offer at Stair in April.) “We keep finding things,” Eerdmans told Introspective several weeks before the Stair sale. “The number of lots is growing by the day. And the sale will be more affordable. The average high estimate at Sotheby’s was about three thousand dollars. At Stair, it will be about nine hundred dollars. I’m hearing that all the young assistants at Sotheby’s are renting vans” in anticipation of scoring pieces for their own apartments. For her part, Eerdmans thinks the reemergence of a taste for over-the-top traditional is “a thing”: “We’ve been living in such tortured, stressful times that there is a swing toward wanting to create a cocoon in your private space, bringing in things that cheer you up, instead of living in a Zen monastery that looks like a hotel. I could be wrong, but I don’t think I am.”

Get the Look

Shop Mario Buatta’s trademark style