January 19, 2020The foreword to the new book Site: Marmol Radziner in the Landscape (Princeton Architectural Press) wasn’t written by a designer or even a critic. Instead, California architects Leo Marmol and Ron Radziner asked a novelist, Mona Simpson, to comment on their work. One of Simpson’s strengths is that she tells the truth. Here, that means debunking an idea that has been key to Southern California residential architecture at least since the early postwar Case Study Houses sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine. In Los Angeles, nighttime temperatures drop “all at once,” Simpson writes. Consequently, “most of the indoor-outdoor life promised by modernists is experienced indoors, through glass.” Her idea of living with nature on a chilly evening? “A tangle of sycamores under a crescent moon . . . seen from a warm living room in a comfortable chair.”

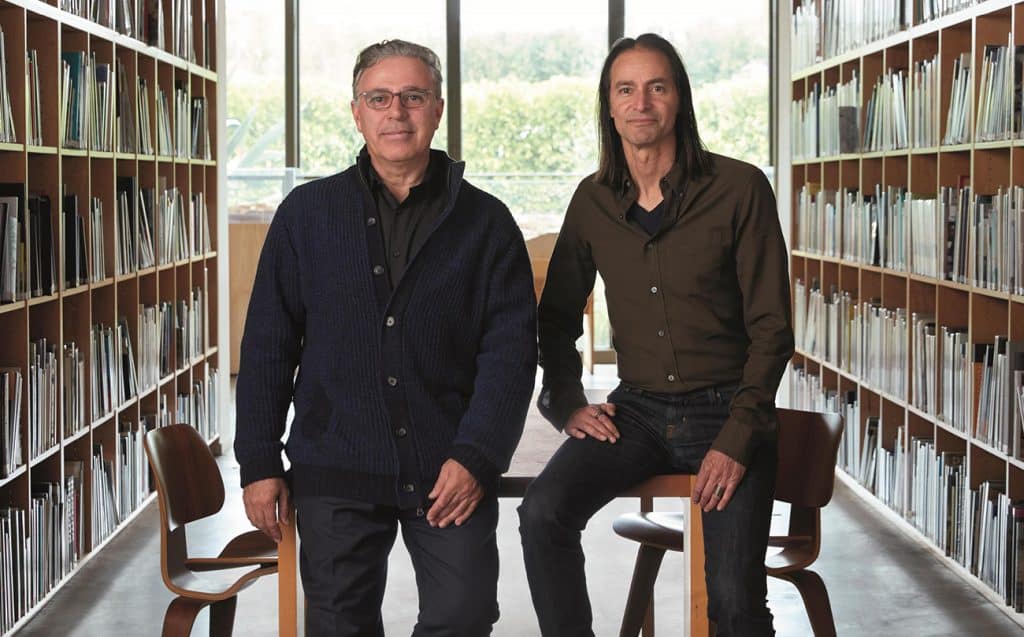

Los Angeles–based architects Leo Marmol (left) and Ron Radziner have released a new book, Site: Marmol Radziner in the Landscape (Princeton Architectural Press), that provides insight into the ways their designs both respond to and provide carefully considered views of the homes’ natural surroundings (photo by Roger Davies). Top: The living room of Radziner’s own residence affords a view of L.A.’s Mandeville Canyon through its floor-to-ceiling walls of glass. The artwork over the fireplace is by Tony Lewis, while the sofas and ottoman are by Living Divani. The Ton A.C. Alberts for RAAK Zodiac floor lamp in the back right corner, the Joaquin Tenreiro coffee table and the Kari Ruokonen floor lamps were all found on 1stdibs (photo by Trevor Tondro).

Simpson, who has been a friend of Radziner’s for years, tells of being in one of his houses during a thunderstorm. Watching the weather through the living room’s triple-height wall of glass was, she recalls, “like being outside in all the wild beauty without any of the real discomfort.”

In the kitchen of a house in L.A.’s Venice neighborhood, Marmol Radziner used walnut on the walls, ceilings and custom cabinetry to create a unified and warm look. The room, which functions as the hub of the residence, looks out to the backyard, pool and patio, as well as in, to other indoor spaces. Photo by Joe Fletcher

In other words, in Simpson’s view, modernist houses are really terrariums in reverse: glass containers with nature kept outside. Mies van der Rohe, one of the greatest architects of the 20th century, would almost certainly agree. If for Le Corbusier houses were “machines for living in,” Mies saw them as machines for viewing. But his experiments with floor-to-ceiling glass, as in the Farnsworth House, in Plano, Illinois, were only partially successful; it took new materials that came along after Mies’s time to make these reverse terrariums comfortable to live in.

The architects note that Marmol’s own weekend home, in Desert Hot Springs — about two hours east of L.A., near Palm Springs — sits within, rather than above, its surroundings. This allows it to engage with the land more fully. As one climbs up the stone path, an opening in the facade offers views of the nearby San Jacinto Mountains. Photo by David Glomb

Now, Marmol and Radziner create comfortable glass houses in a wide variety of settings. Site is organized into four sections that are based not on the structures themselves but on their surroundings: canyon, desert, urban and woodland. Although many of the book’s 200-plus photos (by 20 different photographers) are of interiors, barely one is without a view of nature; many, in fact, show more trees than furniture.

Marmol’s Desert Hot Springs house was the first residence the architects created using prefabricated pieces. All the furnishings on the patio are of Douglas fir and designed by the firm. Photo by David Glomb

Marmol, the firm’s managing partner, and Radziner, the partner in charge of design, are known for their sensitive renovations of houses by California’s mid-century greats, including Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler. But where those architects, missionaries of the International Style, were interested in proving that a certain kind of structure was suitable for every site, Marmol and Radziner create houses that vary dramatically according to location. In a Q&A included in the book, Marmol remarks, “The negative potential of ignoring site is unimaginable.” Radziner concurs. “I think we’d have a slightly better chance of ignoring the client [or] the budget,” he says, noting that “ultimately, the beauty of a building depends on architecture and site being in harmony.”

Radziner designed the Mandeville Canyon house “as a series of long rectangles that slide by each other,” the architects write, noting that this leaves room for the numerous old sycamore trees on the property. “The precision of the architecture accentuates the organic qualities of the site.” Photo by Roger Davies

One way the architects achieve this harmony is by using materials that complement their settings, such as sand-colored stucco in the desert and, often, wood in woodlands. This extends beyond the exterior sheathing. In Marmol Radziner houses, “Counters in bathrooms and kitchens seem to be made out of the stones outside,” Simpson writes, going on to note that such gestures make the houses, although sometimes large and always carefully thought-out, “seem as modest as nature.”

The sunken living room of a house in Amsterdam provides “a perspective that is closer to the earth but still open to shared spaces,” the architects write. The space gives on to the double-height kitchen, which serves as “the heart of family activity” in the home. Photo by Ossip van Duivenbode

The firm’s houses are often made of dark materials, since, the architects point out, every landscape incorporates shadows. One of the best examples is Radziner’s own residence, in Los Angeles’s rural Mandeville Canyon. In deciding to use nearly black brick for the exterior — and for many of the interior — walls the architects say they “considered how vivid nature looks when viewed from the entrance of a dark cave.”

The house was also designed to respond to the existing flora. In plan, it wends its way around a stand of sycamores that took root long before it was constructed. Again, Simpson is spot-on: “You get the feeling these architects find the trees they want and built around them.” Sometimes, though, Marmol and Radziner add vegetation, as for a house occupying a swath of sparse desert terrain in Scottsdale, where they used mesquite and palo verde trees as privacy screens.

The Amsterdam house’s use of brick inside and out echoes that of the Bauhaus-style residences surrounding it. The living room looks out to the property’s gardens, which the architects conceived to evoke “a wild, native feeling,” similar to the aesthetic of the public green space separated from the house by a 50-foot-wide canal. Photo by Kasia Gatkowska

The settings of the structures in the book’s “urban” section aren’t especially urban (it would be interesting to see Marmol Radziner do a New York townhouse). Even a house in Amsterdam, the only project in the book outside the western U.S., is on a spacious, wooded site. In these suburban settings, the architects avoid building walls around the residences, to avoid diminishing the feeling of community. When a client demands a wall, Marmol says in the Q&A, “we often pull it back to allow for an adequate landscape buffer between that wall and the street.”

Its rocky hillside setting in the Mojave Desert provided the inspiration for this Marmol Radziner house overlooking the Las Vegas Strip. “The architecture,” Marmol and Radziner write, “is oriented around both the natural light of the desert and the city lights.” The building comprises 37 interlocking steel-frame prefab modules, which the architects designed and then had constructed in their factory. Photo by Jill Paider

One of the architects’ finest urban houses is on a (wall-less) quarter-acre lot in Venice, California. Marmol and Radziner placed the structure away from the street and surrounded it with vegetation. The kitchen and breakfast room are sunken, so that, from inside, the landscape is experienced at eye level. To avoid overpowering the older, single-story houses on the block, the architects set the second floor back from the first (which has lushly planted roofs); it’s as if the neighborhood got a small multilevel park along with a new dwelling.

The house’s prefab elements form “a layered canopy of extended flat roofs and trellises to cast shadows across all integrated outdoor spaces, including the pool,” the architects write. Photo by Joe Fletcher

Among Marmol Radziner’s great achievements is making houses that are prefabricated yet fully responsive to their sites. (Flipping through the book, you’d have a hard time guessing which of the 19 structures are prefab.) Their experiments with factory-built houses began in 2005, with a weekend house for Marmol’s family in Desert Hot Springs. A series of metal boxes, some enclosed and others open to the elements, are positioned almost like picture frames. A few years later, the architects built a much larger — 12,000-square-foot — prefab house in Las Vegas for casino mogul Jim Murren. In that case, the 37 steel-framed elements weren’t just lowered into an existing landscape — the site was sculpted to make room for a sunken, and thus shaded, basketball court, a pool and other amenities for Murren’s young family.

The owners of this home in Northern California’s Mendocino County “love this site for its wild nature and wanted a vacation house where both they and the earth would be undisturbed,” the book reveals. “A prefabricated house was a logical choice: the building process is minimally intrusive, and on the site, a prefab home floats slightly above the land on a plinth, leaving its surroundings largely untouched.” Photo by Joe Fletcher

Not all the firm’s prefabs are in the desert. One is on 160 acres in Northern California’s wooded Mendocino County. There, the client’s desire to leave the ground undisturbed made building the house remotely and in pieces, and then delivering it by truck, a smart strategy. A modest 2,200 square feet, it is as simple as Mies’s Farnsworth House, except that its glass walls slide open to create connections to the outdoors that even Simpson would approve of. Otherwise, there are no flourishes to detract from the rolling hills, dotted with oak trees, and the jagged mountains in the distance. “The quality of the site,” Marmol and Radziner write in the book, “informed the clarity of our architecture.”

To paraphrase Joyce Kilmer, “I think that I shall never see a house as lovely as a tree.” Marmol and Radziner make lovely houses, but they know real beauty when they see it.

Shop Ron Radziner’s Quick Picks on 1stdibs