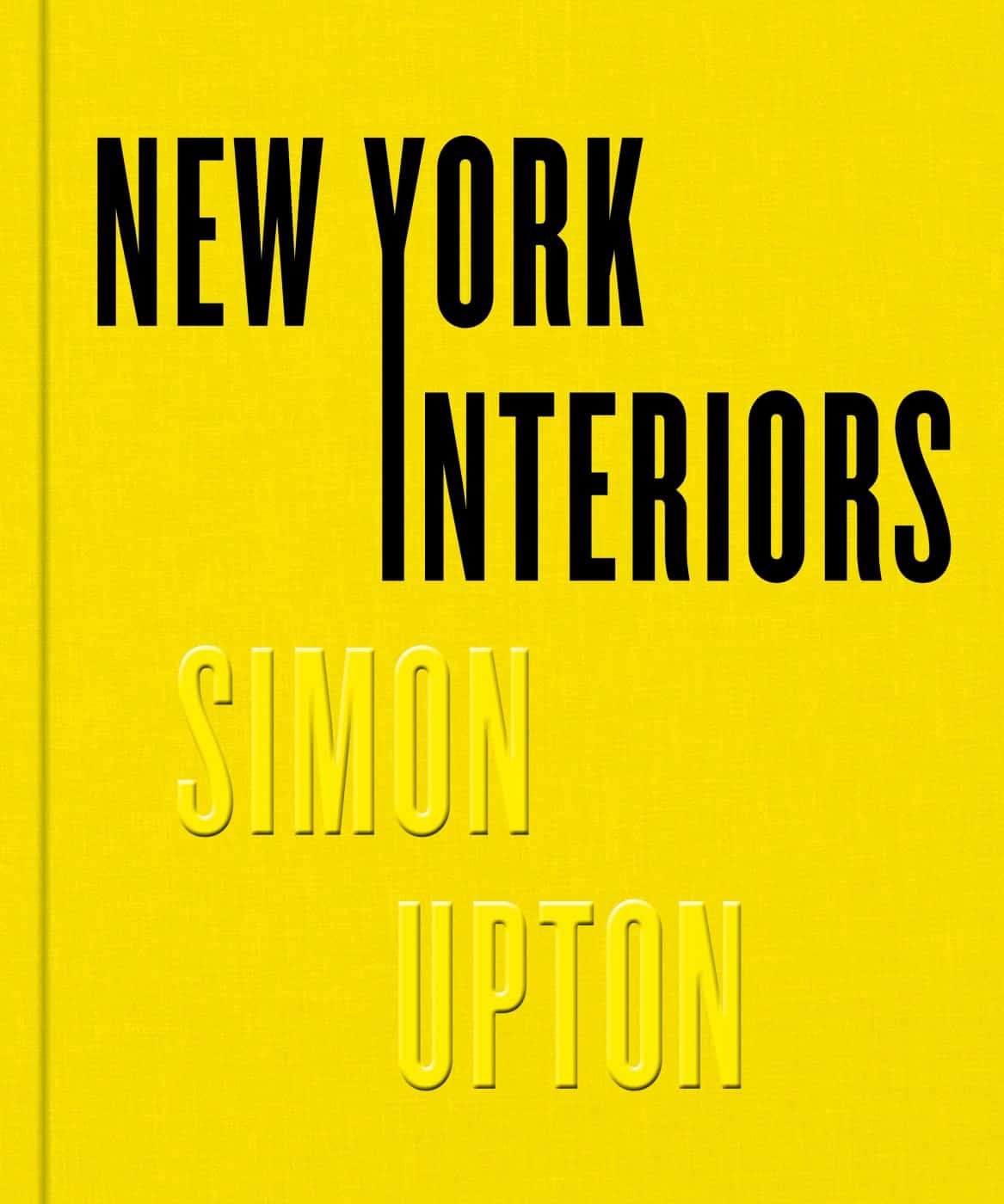

November 13, 2021Over the course of more than two decades, British photographer Simon Upton has made a name for himself photographing domestic interiors and the people who live in them — among them, movie stars, creative types and British aristocrats — with a blend of elegance and warmth that makes him a favorite of prestigious magazines.

And although this work has taken him around the world again and again, he harbors a particular fondness for New York, as illustrated in his first monograph, New York Interiors (Vendome Press).

What is it that Upton finds so very appealing? As he writes in the book’s preface, “In a reflection of the city itself, the inhabitants of New York represent a melting pot of some of the most creative, interesting, resilient, hard-working, and fun-loving characters that it has been my pleasure to get to know.”

Divided in two, the book features 21 Manhattan homes in its “City” section and 8 nearby country retreats in “Getaway.” Upton tells Introspective that because so many people leave Manhattan on the weekends for elsewhere, “it was equally important to me to show where they escaped to.”

The text associated with each home is by its interior designer or its owner, many of whom are themselves designers.

Photography offers “that treat of meeting people who are inspiring,” Upton says. “It’s why I like what I do so much. I really do see interiors and portraits as the same thing.” Indeed, his serene images capture the essence not only of every interior to which he turns his lens but also of that interior’s occupants.

Take his photos of the Soho loft owned by designers Timothy Haynes and Kevin Roberts. The duo populated their home’s large-windowed, white-walled spaces with sleek but beautifully crafted furniture by designers like Gabriella Crespi, Tommi Parzinger and Garouste and Bonetti and filled it with works by such blue-chip artists as Andy Warhol, Donald Judd and Glenn Ligon.

Upton’s images uncover a casual elegance that says much about Haynes and Roberts and how they want to live — especially in contrast to the restrained yet sometimes opulent homes they design for others.

In an entirely different vein, Upton composed dramatic images to show off the way designer Julie Hillman combined old and new in the remarkably well-preserved early-20th-century Fifth Avenue maisonette of a contemporary-art collector.

In the den — where a Pierre Chapo coffee table keeps company with floor lamps by Serge Mouille and Charles Trevelyan — Upton’s keen eye captures not only the contrast between the traditional architecture and the modern and contemporary furnishings but, no less important, the lovely bright side light from an unseen window, reflected off the room’s dark gray lacquered walls.

In the living room, Upton highlights other contrasts, taking advantage of light and shadow to bring out the curving shapes of the sculptural furnishings. Here, a Carl Malmsten daybed with classic lines separates two seating areas, one containing exuberant armchairs by Fernando and Humberto Campana, a Hubert Le Gall coffee table and an elegantly precarious-looking stacked-disc table by Mauro Mori — all against a backdrop of artworks by Vik Muniz.

A more lighthearted feeling pervades the Upper East Side apartment of Carol Prisant, the longtime New York editor for The World of Interiors, for which Upton often works and whose editor in chief wrote the book’s foreword. Upton clearly holds Prisant — who died, at the age of 82, not long after writing her entry for the book — in high esteem.

“I can’t think of an apartment that fit a person more perfectly than hers,” he says, adding that she was “quite individual, gregarious and eccentric, yet hugely perceptive.”

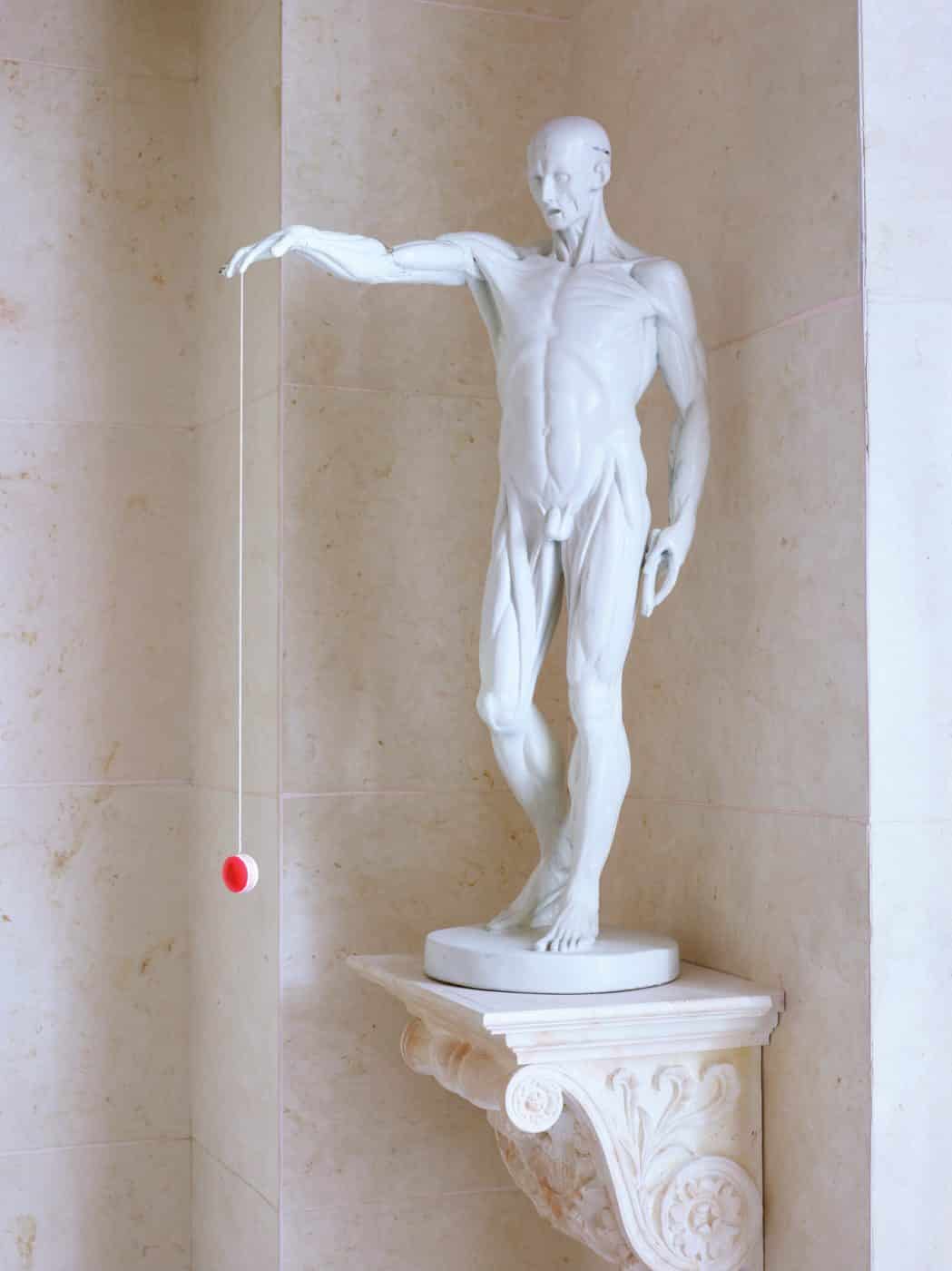

Upton’s photographs discreetly and affectionately convey that spirit. Through his lens, her contemporary take on classicism appears spare and elegant, its modest materials — painted plywood floors and marble-patterned wallpaper — presented as if priceless. And he lovingly points up Prisant’s humorous touches, like a plaster reproduction of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s Flayed Man sculpture, a yo-yo dangling from its hand.

The country houses in the book’s “Getaway” section range from rustic to grand. One of the most intriguing belongs to artist Cary Leibowitz and landscape designer Simon Lince, whose Harlem townhouse is in the “City” section.

This Hudson Valley estate, part of which dates to 1795, got a surprising addition in 2011 by influential postmodernists Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. The two-dimensional chinoiserie facade they created is echoed inside by a two-dimensional rendering of a fireplace mantel adorned with portraits of the architects, who also conceived the adjacent dining table and chairs.

Upton’s images of the home reveal its owners to be as eclectically eccentric as its design.

The older parts of the house include what Leibowitz calls the “Grandma Moses Room,” alluding to the outsider artist’s 1950s fabric that he selected to adorn the furniture and windows.

Among the artworks he and Lince chose for other rooms are a loose-lined print by Jonathan Borofsky, mounted above a golden-hued fringed sofa that belonged to Oprah Winfrey, and an unwoven-rope sculpture by Katharine Umsted that resembles a horse’s tail.

In the two-story stairwell, the couple hung vintage photographs of tour groups at Mount Vernon salon-style, covering the walls from floor to ceiling. Upton terms Leibowitz’s curation “thoroughly inspired.”

Upton’s images of another Hudson Valley property — this one belonging to architect David Mann and his partner, Fritz Karch — are a far more muted, like the home itself. Mann and Karch have let their house’s 1783 Federalist architecture (which, Mann notes in the book, “underwent a Greek Revival in the 1830s”) speak for itself, placing the furniture “as if it were sculpture.”

The photographs here illustrate the couple’s refined sensibility, displayed in generously proportioned rooms decorated with just enough furniture and art to make each space feel even more grand.

This is perhaps best exemplified by the dining room, where they mounted a photograph of Tupperware by Richard Caldicott above the fireplace and set Paul McCobb chairs around a classical-looking cast-concrete and resin table.

The same discreet elegance is evident in the central entry hall, which contains a console, its top supported by caryatids sculpted by Hubert Yencesse, that was originally commissioned by Jacques Adnet as a fireplace.

In his text in the book, Mann draws attention to the effect created by “the play of shadows as the sunlight moves around the house and the artwork and furniture are spotlit in turn.”

That worked very well for Upton, who says, “My ambition is always to use daylight.”

Mann and Karch’s house, Upton concludes, is imbued with “a remarkable feeling of ease.” And that’s something you could very well say about his photographs throughout New York Interiors.