October 10, 2021In his more than 30 years at the San Francisco–based interior design firm ODADA — which he took over from founder Orlando Diaz-Azcuy in 2013 — David Oldroyd has worked on scores of residences in Hawaii. But few have as much history as this 1930s house on the western slope of Diamond Head, the volcanic crater overlooking Waikiki.

Conceived by Harry Sims Bent, a New Mexico–born architect best known for museums and park buildings in Los Angeles and Honolulu, its colonial-by-way-of-California style recalls an era when families arriving from the mainland tended to look over their shoulders rather than embrace island traditions. That included the interior design. When Oldroyd’s clients bought the house a few years ago, there were “fringes and tassels on every piece of furniture, and there were velvet drapes over the windows,” he says. “It was really heavy-handed.”

By contrast, his clients, he says, are “youthful, adventurous, playful, lovers of simplicity and purposefulness.” And over the years, they have put together a superb private collection of Hawaiian Abstract Expressionist art, mostly from the middle of the 20th century.

The homeowners tasked Oldroyd with modernizing the house — a project that included making space for their many paintings and sculptures — while respecting its nearly century-old roots.

Luckily, the building itself helped point the way: An exploratory surgery of sorts revealed that the dropped ceilings concealed original teak cladding, richly colored and textured but straightforward and unpretentious.

One of the teak ceilings forms a canopy over the living room, which faces the dining room across a formal, strictly symmetrical foyer. Playing up that symmetry, Oldroyd gave the rooms identical Stilnovo chandeliers from the 1950s. “It’s wonderful to walk in and see the pair of them crowning the two rooms,” he says.

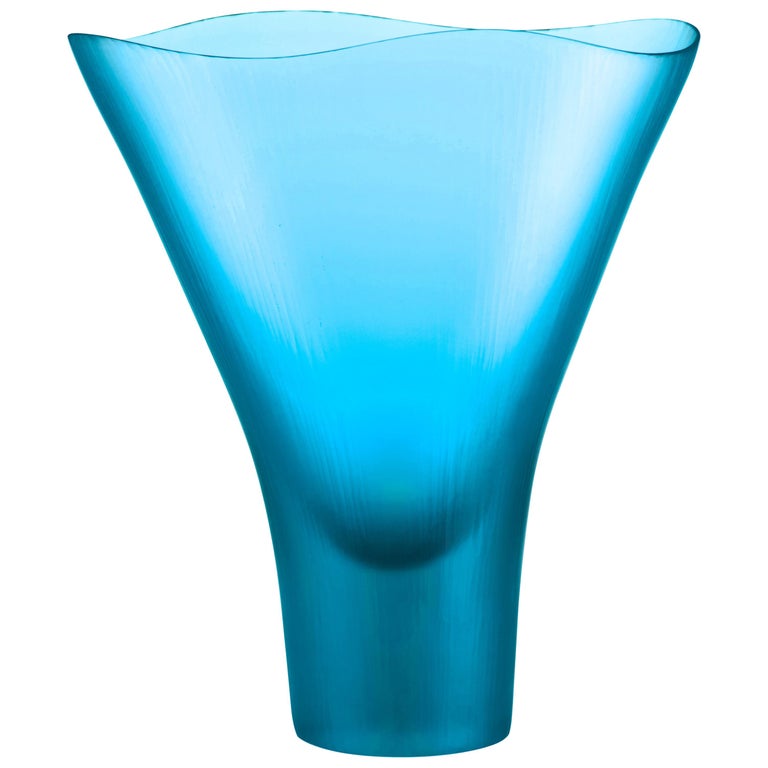

In an even more dramatic (and symmetrical) move, he installed rugs that together stretch from the far end of the dining room to the far end of the living room. In the foyer, where they meet, they are the deep blue of the ocean, but on either side they fade to turquoise and pale seafoam and celadon, like the waters off Oahu.

“It was a bold move to stretch color from the far end of the dining room to the far end of the living room in a single continuous wave,” Oldroyd says, noting that the clients needed a bit of convincing. After all, the rugs were “not inexpensive” and, because they are 100 percent silk, can be tricky to maintain.

“Walking on them creates foot patterns that reveal the sheen of the silk in wonderful, asymmetrical ways and also look like eddies in the ocean,” he says. He persuaded the clients not to rake the eddies away. Instead, the husband vacuums the rugs himself, then he walks around, reestablishing the beautiful, seemingly random patterns with his feet. Says the designer, “He’s very proud of the effect.”

But how could furniture compete with the rich seascape underfoot? In the living room, a Vladimir Kagan sofa upholstered in a white bouclé is big enough and bright enough to hold the floor. The coffee table, which Oldroyd designed, is oval, echoing the shape of the sofa; together, he says, “they move you around the room.”

The leather-covered table is partially gilded. (Gold, Oldroyd says, brings a richness to the room but has to be used sparingly.) The space also contains a vintage wingback chair from Italy, a Biedermeier side chair and, to the right of the fireplace, a console the client treasured and wanted to retain. As Oldroyd puts it, “We nodded to the history of the house without adding clutter.”

A shearling-covered, bronze-footed Pieds de Bouc stool by Marc Bankowsky from Maison Gerard adds a bit of whimsy. Oldroyd exchanged the heavy drapes within the bay windows for linen. When the sun shines through the shear fabric, “the room just glows with natural light,” he says.

That light illuminates an array of pieces, gathered on the coffee table, by Toshiko Takaezu. (A ceramist born to Japanese immigrant parents in Hawaii in 1922, Takaezu studied at the Cranbrook Academy of Art, in Michigan, and later taught at Princeton University. She retired in 1992 and spent a decade in Hawaii before she died, in 2011.) Heavier linen drapes, on either side of the bay windows, keep the sun from hitting, and fading, important works on canvas or paper.

Above the console is a painting by Ben Norris, a California native who turned out lush tropical landscapes while teaching at the University of Hawaii from the 1930s to the 1950s. The vessel on the console is by David Kuraoka, who was raised on Kauai and named a Living Treasure of Hawaii in 1987.

The focus of the dining room is a large mid-20th-century table. “It’s wood wrapped in a sort of lacquered parchment paper, which has a wonderful patina,” Oldroyd says. The French Art Deco dining chairs by Pierre Bloch and Charles Dudouyt are from the ’30s, the same era as the house. An antique burled-wood cabinet reflects the teak overhead. Indeed, Oldroyd says he used the cabinet to “bring the ceiling into and across the room.” The large metal sculpture is by Satoru Abe.

What is now the couple’s music room, complete with BABY GRAND PIANO, used to be a covered porch filled with VICTORIAN WICKER FURNITURE. (Oldroyd believes it was enclosed in the 1960s.) It, too, has a teak ceiling, but because it was outside, the teak had both roughened and faded, developing the weathered appearance of driftwood.

To make the ceiling really glow, Oldroyd designed a pair of what he calls “uplight chandeliers,” inspired by the shell lights popular in the 1930s. The custom sofa and club chairs are “very large and very deep.” The coffee table, of preserved weathered teak, is equally overscaled. The red velvet stool, which isn’t, was a gift to the couple from a friend.

“The sinuous lines of the arms of the two wood-framed upholstered chairs bring a little femininity to the space,” Oldroyd says. The arms also seem to be communicating with the ruffled edges of the uplights. On the travertine floor is a custom rug woven of wool and cashmere. Above the sofa is Isami Doi’s Mystic Pilgrimage, which Oldroyd thinks of as the “devil/angel painting.”

To the left of that artwork is one of several pieces in the house by Tetsuo Ochikubo. Born in Hawaii to Japanese American parents, Ochikubo served in the U.S. Army during World War II before training at both the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the Art Students League in New York.

The credenza is a piece the clients owned that Oldroyd says he fell in love with “for its age and its softness and its character.” He paired it with two works by Kauai-born artists: Atop is a sculpture by Bumpei Akaji, and hanging above is a painting by Reuben Tam, titled Marine Forecast.

Oldroyd persuaded the clients to let him paint the walls of the music room a pale lavender, a choice so controversial that they referred to it as “the L-word.” But Oldroyd believed it would “make the art really jump.” And it does just that for the large painting by Maui-born master Tadashi Sato, which enjoys pride of place on its own wall.

Fulfilling the wife’s fondest wish, Oldroyd created a library out of an enclosed porch, lining it with shelves of American walnut that can hold several thousand books. He designed a pair of daybeds and upholstered the bare walls in linen. The arched window was in an odd place, so Oldroyd incorporated it into a niche, creating a bit of symmetry and the perfect place for a small needlepoint work by Antonia Krupka Hoch.

“It’s great working with clients whose aesthetic is so closely aligned with my own,” says Oldroyd. “When I got here, the house didn’t feel like them, and now it does.”