October 18, 2020Osvaldo Borsani may not have the same name recognition as his compatriots and fellow modernists Carlo Scarpa and Giò Ponti, but a new show of his furniture makes a case for the mid-20th-century Italian designer as a truly great talent.

Flashes of rich wood are everywhere in the exhibition, at the New York City gallery Donzella through the end of the year, as are particular lines and forms that could only come from the middle decades of the last century. The 25 pieces on view are grouped into three categories — seating, cabinets and tables — and all were made in the 1940s and early 1950s. Six of them were sourced from the Borsani family itself, a coup for dealer Paul Donzella.

If you can’t quite remember the last Borsani show, there’s a reason. “I’ve been aware of his work for at least twenty-five years now, and I’ve never heard of another exhibition here in the States,” says Donzella, a passionate advocate for the designer’s work.

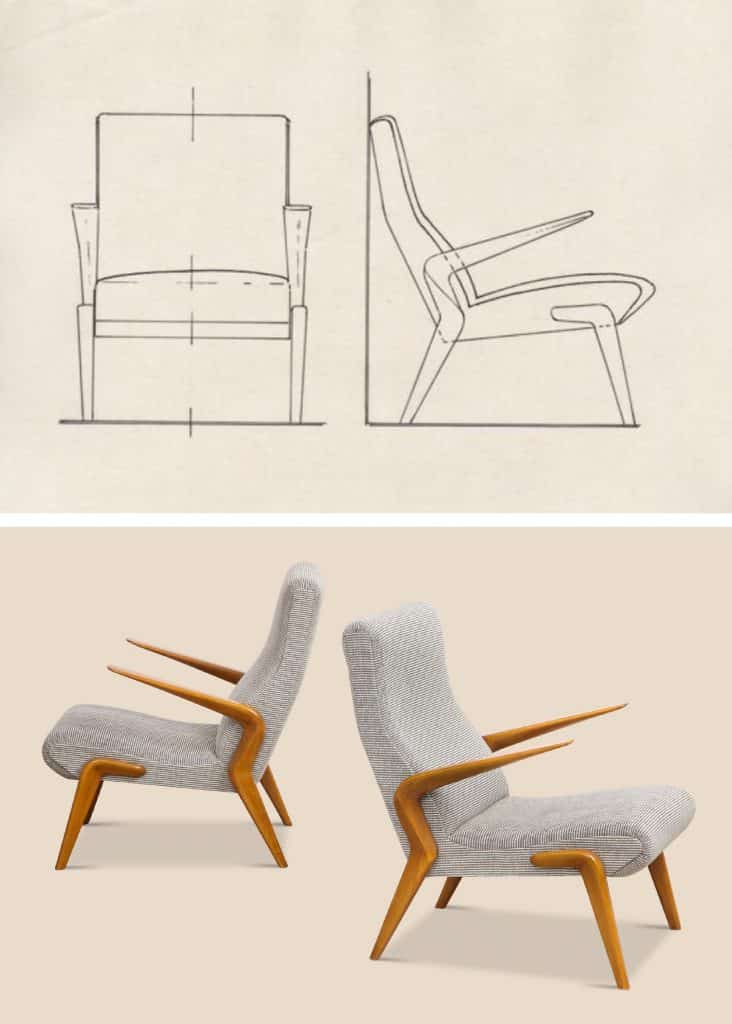

Borsani is most famous these days for founding — in 1953, with his twin brother, Fulgenzio — the company Tecno, an office-focused maker of industrial design. When they were originally released, Tecno pieces like the P40 lounge and D70 sofa bed were acclaimed as cutting-edge, and they are still considered groundbreaking in their adaptability and functionality.

Donzella has a few Tecno pieces in his show, including the P99 desk chair, from about 1957, fashioned from enameled steel, rubber, brass and leather. But most of the pieces on display are from Borsani’s earlier, more bespoke phase, during which he made grander and at times playful furniture for Arredamenti Borsani Varedo (ABV), the family atelier founded by his father, Gaetano.

Donzella recalls noticing pieces from this pre-Tecno period some 20 years ago: “It’s incredibly beautiful, detailed work. I was like, ‘Whoa, it’s the first time I’m seeing this other side of Borsani.”

The diversity of his oeuvre may explain why he’s lesser known. “Borsani has always been a little difficult for Americans to grasp,” says Christian Larsen, a curator at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design. “His style varies so widely, from the exquisitely detailed bespoke cabinetry of the Milanese classical tradition to eminently functional industrial modernist furnishings.”

The supremely chic Triennale dining chairs (1951) displayed at Donzella are carved from sensuous mahogany and sport an unusually shaped pierced splat crowned by what looks like part of a butterfly joint. An onyx-topped walnut coffee table has dramatically curving legs that, as they meet on their ascent, form a keyhole shape.

One of the showstoppers is a wall-mounted sideboard, from around 1943, in Italian walnut, mahogany and brass. It rests on three massive brackets shaped like emphatic apostrophes, and its coffered front and sides are adorned with a series of portraits of carved animals. Somehow, it manages to be both monumental and whimsical at the same time.

A ca. 1940 wardrobe unit in light Italian maple and painted wood is more delicate and less fantastical, with a lovely dentilated top; the largely plain doors don’t need adornment, given the rich grain of the wood. This piece embodies another quality that Donzella finds in all the best Borsani work. He describes it as “a level of restraint that feels Milanese to me.”

The sideboard and the wardrobe evidence Borsani’s roots in traditional design. He never cast that training and knowledge aside. “There’s often a nod to classicism,” Donzella says of the designer’s work. Certainly Borsani mined what the dealer calls “the European tradition of fine woods,” especially maple, walnut, mahogany and rosewood.

And yet, he put his own spin on the use of these materials. “His work was less about intricate inlays,” adds Donzella. “It was more about turning the wood into a medium for sculpture.”

Borsani went to art school, then studied architecture at the Politecnico di Milano. While still a student there, he designed and built Casa Minima, a Rationalist home of the future, for the 1933 Milan Triennial, working with two other architects. The small but beautifully detailed house for a family of three made a huge splash. Borsani took over ABV in 1937 and soon after started designing Villa Borsani, a brick-and-stucco modern home with custom furnishings that he built just outside Milan. “To really get to know Borsani, one should tour this estate,” says Larsen. “His extraordinary elegance and creativity are on full display there.”

Open today only for special events — during Milan Design Week, for example — the villa is revered by people in the design field for its strong horizontal lines (reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright’s), rich details (such as the staircase incorporating Murano glass) and sunken living room. It features, among other avant-garde collaborations, a fireplace hearth by Lucio Fontana, famed for his slash paintings and a good friend of the designer’s. “There’s so much material like that in the house,” says Donzella. “He was a great collaborator with artists.”

Donzella got to experience the villa personally in 2018, when he traveled to Milan to see a significant show of Borsani’s oeuvre mounted by the Triennale di Milano design museum. While there, he toured the house, met with the family — both Borsani’s daughter Valeria and grandson Tommaso are architects — and used the opportunity to further his understanding of the work.

On the trip, Donzella presented the family with the idea of an exhibition, explaining what a fan he is of Borsani’s talent. At first, the gallerist explains, they thought he was referring to the Tecno work, because of its museum presence and many awards. But Donzella told them, “The things I relate to more are the pieces for ABV, and I’m much more interested in the undiscovered material.”

In the end, he was able to buy six pieces, all of which were featured in the Triennale show, including the 1943 sideboard and a similar piece from 1945, a wall-mounted carved console table in maple.

“I think when it’s your family, you’re proud to have this material go to New York and be in a really good show,” Donzella says of the Borsani family’s motivation. “I’m hoping that they’re very happy with what I’ve put together — and I hope to be able to buy more from them, to be quite honest.”

Borsani’s versatility is certainly part of his legacy, but Donzella also sees a consistent sensibility throughout the work. All the pieces are tasteful, but also surprising and even a bit witty — revealing what the dealer terms a “sense of sculptural humor.”

“To me,” Donzella says, “it’s design nirvana.”