February 27, 2017In his ninth decade — and showing no sign of slowing down — Richard Solomon continues to run New York’s Pace Prints, the nearly 50-year-old publishing and print-making outfit that complements the blue-chip Pace Gallery (portrait by Emily Andrews). Focused on editions by top artists, it will be at the ADAA Art Show — starting March 1 at Manhattan’s Park Avenue Armory — showing modern and contemporary pieces by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Jasper Johns and Willem de Kooning, among others.

Some great art dealers are failed artists; others, born salesmen. And then there’s a class of dealers who are simply in love with art: collectors who decided to make running galleries their full-time gigs. Richard Solomon falls into that last category.

Solomon, now 82, traces the start of his career to a 1960 stroll in Boston in which he came across a new contemporary art space called Pace Gallery, founded by a young man named Arne Glimcher. “I bought the first thing he ever sold as an art dealer,” says Solomon. “Arne had just opened his gallery. My wife and I were walking down Newbury Street, saw something in the window that we knew we liked, and we bought it. It was a Mirko Basaldella sculpture.”

That purchase proved serendipitous — not only for Solomon but for contemporary art as well. A decade later, he and Glimcher partnered together to found Pace Prints. This editions-focused offshoot has, in the 47 years since its establishment, published etchings, Japanese-style woodcuts, screenprints and intaglios, among other types of multiples, by more than 150 artists, including such stars as Sol LeWitt, Robert Ryman, James Turrell, Kiki Smith and Yoshitomo Nara. Just as importantly, Solomon has served as a cheerleader for the field of printmaking, teaching generations of collectors that prints are not reproductions but rather original, although not unique, works of art that deserve the same respect as any other medium.

“What I try to tell people is, ‘Aren’t you better off, from a long-term standpoint, buying an important print by an important artist, instead of trying to find a unique work that might be of comparable value in monetary terms but no way comparable in aesthetic terms?’ ” Solomon says, sitting in a viewing room in Pace Prints’ East 57th Street flagship. “The most important thing in buying a work of art is that you’re going to like it in four or five years, so it doesn’t give you all that it’s got in your first look.”

Solomon’s art education began in his youth, in Manhattan. His mother, Jeannette, founded a series of art tours for the Radcliffe Club of New York, which benefitted his alma mater, and he often joined her on visits to galleries and to the homes of important collectors. Jeannette collected modern and contemporary art, while Solomon, still in his teens, began amassing drawings from the Weyhe Gallery, on Lexington Avenue. “They were like twenty-five or fifty dollars,” he says. “They were sculptors’ drawings. My mother would give them to me as a Christmas present or a birthday present or just as a present.”

Celebration #1, 1979, by Louise Nevelson

By the time he arrived at Harvard, in 1952, he had acquired the habits of a connoisseur. “My roommates used to kid me because I went to The Coop and bought three little Edgar Degas reproductions and hung them in the bathroom in our suite in Eliot House,” he says. His inspiration was a friend’s uncle, who had three works by Georges Rouault hanging in his bathroom. “I was so respectful of that and impressed by that. If you put art in the bathroom, that was really being a collector.”

After receiving his Harvard MBA in 1958, Solomon remained in Boston to join Stop & Shop, his mother’s family’s business, which invented the self-service supermarket concept a hundred years ago. During his eight years with the company, he grew increasingly engrossed with contemporary art, thanks in part to his burgeoning friendship with Glimcher, who would soon become one of the preeminent gallerists of his generation.”

Glimcher guided Solomon in assembling his collection. (Although Solomon also independently purchased three paintings from the debut show of a young man named Andy Warhol.) Solomon, in turn, started helping Glimcher install shows at the gallery. Yearning for more creative work, he left Stop & Shop in 1967 and moved back to New York to oversee Clairol’s hair-color advertising department. One day, Glimcher, who had also relocated to New York, asked Solomon to finance a complicated edition project by Pace artist Lucas Samaras. Solomon agreed. Then came another project, and another. “Eventually, I said to Arne, ‘Who’s going to sell this stuff we’ve published?’ ” Solomon recalls. “He said, ‘What do you mean, who? It’s you.’ And so I gave my notice at Clairol.”

Green Cone, 2007, by Donald Baechler

The duo partnered on Pace Prints as a vehicle for publishing multiples by Pace’s roster of artists. Solomon knew a thing or two about selling: Not only was his mother’s family in retail, but his father, Sidney, was the CEO of the Abraham & Straus department stores. Solomon started dealing in prints full-time on January 1, 1970. Back then, putting a price of $150 on a print was considered a reach. But Solomon and Glimcher saw that pioneering print publishers had already stoked the market: There was Gemini G.E.L., in Los Angeles; and Tatyana Grosman, of Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE), in New York, where Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg had given printmaking new respectability, plus a dose of cool.

“The theory was, we would allow our artists to publish in-house rather than have them go out to other places,” says Solomon. “In other words, if you looked at the artists of gallerist Leo Castelli [such as Johns and Rauschenberg], who were the bulk of the artists doing prints at that time, they were all being published by businesses that were unrelated to their galleries. We were very lucky, because within five years people like Agnes Martin and Chuck Close and Jim Dine came aboard, and they turned out to be prodigious printmakers and fascinating artists.”

Eventually, Pace Prints welcomed artists from outside its stable, which led to scores of additional fruitful collaborations. Lately, such mid-career artists as Leonardo Drew and Ghada Amer have explored new ideas in the Pace shop.

Many of Solomon’s milestone business decisions have been driven by personnel. In the mid-1970s, for example, the outfit evolved from being strictly a publisher, jobbing out the actual printing, to being a full-fledged print workshop. The shift was due in large part to their taking on the late Joe Wilfer, a paper- and printmaker who had collaborated with Close. “Chuck said to me, ‘You’ve gotta hire this guy,’” Solomon says. “When Chuck says you gotta do something, you do it. So I hired him, which was probably the best thing I ever did.”

“The most important thing in buying a work of art is that you’re going to like it in four or five years, so it doesn’t give you all that it’s got in your first look.”

Changes (2), 1970, by Jack Youngerman

Dine, whom Solomon calls “one of the great, great printmakers” of the 20th century, was also instrumental in the development of the workshop. “I didn’t know anything about printmaking, but we started acquiring equipment,” Solomon says. “Pretty soon, we had a facility in Soho, and we had all kinds of presses and were doing all kinds of stuff in-house.”

It was Dine who took him to meet Aldo Crommelynck in Paris. “I knew who Aldo Crommelynck was because he was the printer for Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, David Hockney,” says Solomon. “He and I formed this partnership where he was producing editions for us. That gave us an opportunity to work with people like Ed Ruscha and Terry Winters. So gradually this thing morphed.”

The print workshop moved from Soho to Chelsea in 1998. More recently, onetime junior staffer Jacob Lewis pushed for Pace Prints to open a Chelsea gallery, which it did in 2007, recruiting younger artists, such as KAWS and Ryan McGinness. Lewis now operates an eponymous contemporary art gallery in the same Chelsea building, in partnership with Pace Prints. And in what may be a unique venture for a commercial printmaker, Pace Prints also built a paper-making studio in Gowanus, Brooklyn, in 2008. (More than 45 years ago, Solomon started Pace Primitive, focusing on tribal art.)

Pace Prints is a frequent exhibitor at art fairs, including the ADAA Art Show. At this year’s edition of the show (opening March 1 at the Park Avenue Armory in New York), Solomon says he’ll be showing modern and contemporary works by Picasso, Matisse, Johns and Willem de Kooning, among others. He is always eager to educate new collectors about the complexities and rigor of printmaking. In exchange, he wants collectors to stop apologizing for shopping for artworks to hang over their sofas. “There’s no bad reason for buying art,” he explains. “To me, using art as decoration is not pejorative. We all do it. It’s part of the aesthetic environment you’re trying to create. It’s an expression of one’s own personal aesthetics.”

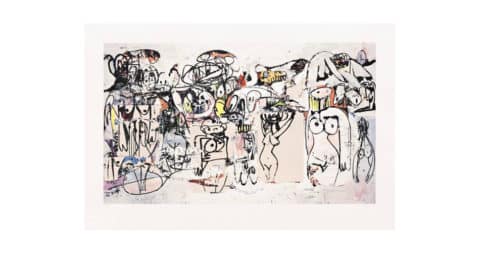

Indivisables #1, 2007, by Karin Davie, from the artist’s series “Pushed, Pulled, Depleted & Duplicated”

Solomon has presided over the publication of thousands of works on paper in his nearly half century at Pace Prints, and he is loath to rank them. He does, however, have a sentimental favorite. “When I was forty years old,” he recalls, “Chuck Close did a fingerprint drawing of me,” part of a startlingly realistic series Close executed with only his fingerprint and an ink pad. Solomon’s mother urged him to buy it. “I said, ‘You know, Mom, I really don’t like it. It makes me look much too old.’ Then, when I was sixty-five, that same work of art came up for auction at Christie’s. By then it certainly was going to be much more expensive than when I was forty, but I felt good about it. I looked a lot younger. I looked pretty good.”

The night before the sale, a Close painting set an auction record for the artist, leading Solomon to fear bidders would send the drawing’s price out of reach. Nevertheless, he arranged for a Pace staffer to bid on his behalf. “I had elaborate hand signals about when to stop because I certainly didn’t want to be recognized as bidding on my own portrait,” he says with a laugh. “For some reason the Pace person didn’t show up. [The auctioneer] started the bidding. It was deathly silence. I held up my paddle sheepishly. Nobody else seemed to want it.” Solomon won the piece handily, but, he says, “I was really pissed off. I said, ‘Number one, nobody recognized me, and number two, nobody wanted me.’ It was one of the funniest experiences of my life.”

The piece still hangs in his library. “Forty years later,” Solomon notes of the portrait, “I look amazingly good.”

TALKING POINTS

Richard Solomon shares his thoughts on a few choice pieces.