August 14, 2017From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today — at the Parrish Art Museum, in Water Mill, New York, through January 21 — contains 75 Photorealist artworks by 32 painters. Among them are Charles Bell‘s Gum Ball No. 10: “Sugar Daddy,” 1975 (Photo courtesy Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York), and Ralph Goings‘s Miss Albany Diner, 1993 (Photo courtesy Heiskell Family Collection). Photos courtesy Meisel Family Collections, New York, unless otherwise noted

There’s nothing especially enchanting about a 1971 Buick Estate wagon — a boxy, beast of a car adorned with muddy brown panels framed in chrome. Unless, that is, it has been positioned just right, photographed, made into a slide, projected onto a canvas and then painted by Robert Bechtle, one of the founding Photorealists. “Taking a very ordinary moment and somehow causing it to become magical through devices which are not even always apparent is something that interests me a lot,” the San Francisco–based artist, now 85, has said. “You have to look twice at it.” Such is the everyday alchemy of Photorealism, and a new exhibition at the Parrish Art Museum, in Water Mill, New York, finds it ripe for a fresh look.

“Photorealists embarked on a new way of seeing and depicting that relied on taking the photographic image, quite literally, as the starting point in their creative process,” explains Parrish director Terrie Sultan, curator of “From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today,” on view through January 21. The exhibition explores the remarkably cohesive and influential yet under-recognized art movement through 75 works by 32 artists, including Bechtle, Richard Estes, Ralph Goings, Chuck Close, Audrey Flack and Charles Bell.

“For me, it was, ‘Wow, something new!’” recalls San Francisco art dealer John Berggruen, for whom Photorealism was part of his “initiation into the art world,” guided by the late Ivan Karp, founder of the pioneering O.K. Harris gallery in New York and a champion of Photorealism. “You could see elements that were familiar from Pop art, but it wasn’t an outgrowth of Pop, just another avenue.”

A direct challenge to Abstract Expressionism’s subjectivity and gestural vigor, Photorealism was informed by the Pop predilection for representational imagery, popular iconography and tools, like projectors and airbrushes, borrowed from the worlds of commercial art and design. “Immediately understandable art, combined with boring, commonplace and non-artistic subject matter, was transgressive in the context of contemporary-art-world expectations,” artist and critic Richard Kalina writes in the book accompanying the exhibition (out August 25 from Prestel). “Photorealism carried the same charge as Pop, but unlike Pop. . . Photorealism never abandoned its artless affect, its look of utter comprehensibility.”

Urban scenes like the Manhattan streetscape of Hotel Empire, 1987, are Richard Estes‘s signature works. “Mostly depopulated, intricately geometrical layers of horizontals and verticals, they indicate a highly formal aesthetic while establishing a distinctive sense of the light, angles and reflections that dominate city centers,” says Parrish director Terrie Sultan, who curated the show.

Goings’s Still Life with Check, 1981, “monumentalizes the inanimate, functional objects that are a constant presence on diner and café tables,” explains Sultan.

Whether gritty (Goings’s isolated trucks and vacant diners) or gleaming (Bell’s rainbow-bright gumball and pinball machines), the subject matter favored by Photorealists is instantly, if vaguely, familiar. It’s the stuff of yellowing snapshots and fugitive memories. The bland and the garish alike flicker between crystal-clear reality and dreamy illusion, inviting the viewer to contemplate a single moment rather than igniting a story.

The virtues of the “photo” in Photorealist works —infused as they are with dazzling qualities that are easily blurred in reproduction — are as elusive as they are allusive. “Much Photorealist painting has the vacuity of proportion and intent of an idiot-savant, long on look and short on personal timbre,” John Arthur wrote (rather admiringly) in the catalogue essay for Realism/Photorealism, a 1980 exhibition at the Philbrook Museum of Art, in Tulsa, Oklahoma. At its best, Photorealism is a perpetually paused tug-of-war between the sacred and the profane, the general and the specific, the record and the object.

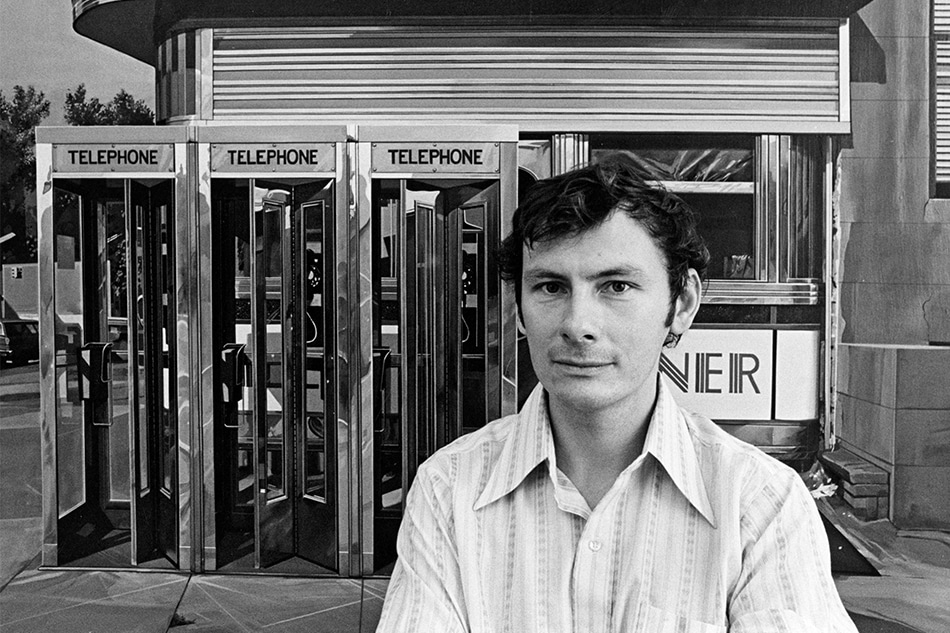

“Robert Bechtle invented Photorealism, in 1963,” says veteran art dealer Louis Meisel, who helped Sultan ferret out the Photorealist works tucked away in the permanent collections of such institutions as the Guggenheim, Whitney and Brooklyn museums. “He took a picture of himself in the mirror with the car outside and then painted it. That was the first one.”

But it was Meisel himself who coined the term. He recalls that, during a 1969 conversation with Village Voice writer Howard Smith, he was grasping for a descriptor of the works in a small group show then on view at his Soho gallery. “I said, ‘Well, these artists are using the camera and the photograph. What about photographic realism — Photorealism?’ ”

Chuck Close’s Nat – Horizontal/Vertical/Diagonal, 1973, is a study for one of a series of large portrait paintings that emulate the photomechanical method of color printing, with separations of magenta, cyan and yellow.

“Meisel is the one who really brought all these artists together and came up with certain standards for Photorealism,” says dealer Jonathan Novak, whose Los Angeles gallery represents such artists as Robert Cottingham, Ben Schonzeit and Bertrand Meniel. “His four volumes on the movement” — Photorealism, Photorealism since 1980, Photorealism at the Millennium and Photorealism in the Digital Age — “come close to composing catalogues raisonnés of the artists included in the books.”

The meaning of the term, which began for Meisel as “a superficial way of defining and promoting a group of painters,” evolved with time, and the core group of Photorealists slowly expanded to include younger artists, such as Meniel, Raphaella Spence and Anthony Brunelli, who traded Rolleiflexes for 60-megapixel cameras, using advanced digital technology to create paintings that transcend the detail of conventional photographs.

For Berggruen, the relatively “limited vocabulary” of Photorealism was a built-in check on its popularity and collectibility. The movement’s lone constant — an emphasis on verisimilitude — is easily written off as little more than trompe l’oeil technical prowess. Or worse.

In a 1974 review for New York magazine titled “Treacle and Trash,” critic Barbara Rose mourned Allan Stone gallery’s Estes exhibition as a triumph for “the silent majority.” Her takedown revealed her reeling from sticker shock (for the price of one Estes, she noted, “one could purchase today in the neighborhood of 50 abstract paintings of quality”) and helped to relegate Photorealism to the dusty attic of American Scene painting. “About Estes’s paintings themselves, there is little to say except that, like Andrew Wyeth’s minutely detailed scenes, they look very hard to do, and hard work has always been appreciated in America,” wrote Rose, who described the artist’s complex cityscapes as “visual soap operas,” expressive only in their “deadness.”

Bechtle bristles at allegations of absolute neutrality, of blind objectivity and abnegation of creative choice. For him, half the fun is waging a sneaky battle against what he has described as “the tyranny of the photo.” His tendency to backstop his subjects, especially cars, with “nondescript architecture” is no accident.

“Photorealism, slotting itself in with a long line of vernacular American realisms, is an art form primarily of our country,” artist and critic Richard Kalina writes in the volume that accompanies the Parrish exhibition, which includes Davis Cone’s State-Autumn Evening, 2002. “Most of its subject matter reflects the American cultural landscape.”Photo courtesy of The Collection of John Gordon

Monumentally scaled Photorealist paintings like Flack’s Wheel of Fortune (Vanitas), 1977–78, often take one or two years to complete. According to Sultan, Flack describes her “Vanitas” series as “heavy,” laden as it is with social, political and personal references. Photo courtesy Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, Gift of Louis K. and Susan P. Meisel

“It’s not a neutral choice. It’s a choice which is very pointed. In choosing the combination of the architecture plus the vehicle, the vehicle also has to be pointedly nondescript, like a Buick station wagon in front of a stucco or tract-type house,” he has said. “I suppose one of the reasons for having these things be more nondescript is that it allows the objects to function maybe a little more like bottles and oranges and so on — to function as a still life.”

Helping to shed new light on Photorealism in the Parrish exhibition is a selection of 37 rarely exhibited small watercolor and acrylic works on paper. Some of these pieces were created for group shows at Meisel’s gallery. “Back in the early seventies, there were critics who were saying the reason that Photorealists used the camera was that they couldn’t draw, which was ridiculous,” Meisel says. “My wife, Susan, decided to do a show of watercolors and works on paper by the Photorealists, because you can’t fake a watercolor! If you can’t draw, you can’t do it. You make a mistake, you throw it away.”

“I think there is a misunderstanding regarding the importance of the hand of the artist in Photorealist works,” says Sultan. “With many different artists participating [in “From Lens to Hand”], viewers will have the opportunity to compare different styles and approaches the various artists have taken to express and depict their subjects. People will be surprised to see that, when viewed up close, there is a tremendous amount of individual expression involved.”