February 23, 2020A collection of Italian Radical design amassed by creative director Dennis Freedman is the subject of a new exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The movement included Archizoom, whose Superonda sofa from 1976 is pictured above (photo courtesy Centro Studi Poltronova Archive). Top: Freedman stores many pieces from his collection — including ones by Mario Botta, Studio 65 and Andrea Branzi — in a warehouse near his home in New York’s Hamptons (photo by Stefan Ruiz).

In the late 1960s, when college-age Americans were protesting the Vietnam War and embracing a cultural revolution still best described by the phrase “sex, drugs and rock’n’roll,” their counterparts in Italy — cadres of young architects, architecture students, artists and designers in Florence, Turin and Milan — were feeling restless as well. Their rebellion took the form of an avant-garde art movement that produced exuberant conceptual furnishings and objects that were neither practical nor very commercial.

Among the best known of these is Piero Gilardi’s 1968 Sassi, molded-foam seating that mimics an outcropping of rock; and Studio65’s 1971 Capitello, a classical Greek column truncated and laid on its side. Influenced by Pop art, minimalism and Arte Povera, or “poor art,” which made use of such materials as soil, rags and twigs, Radical design, a term coined by the Italian author and curator Germano Celant, was a joyful exploration of form, color and material deployed in a way that challenged the existing social order.

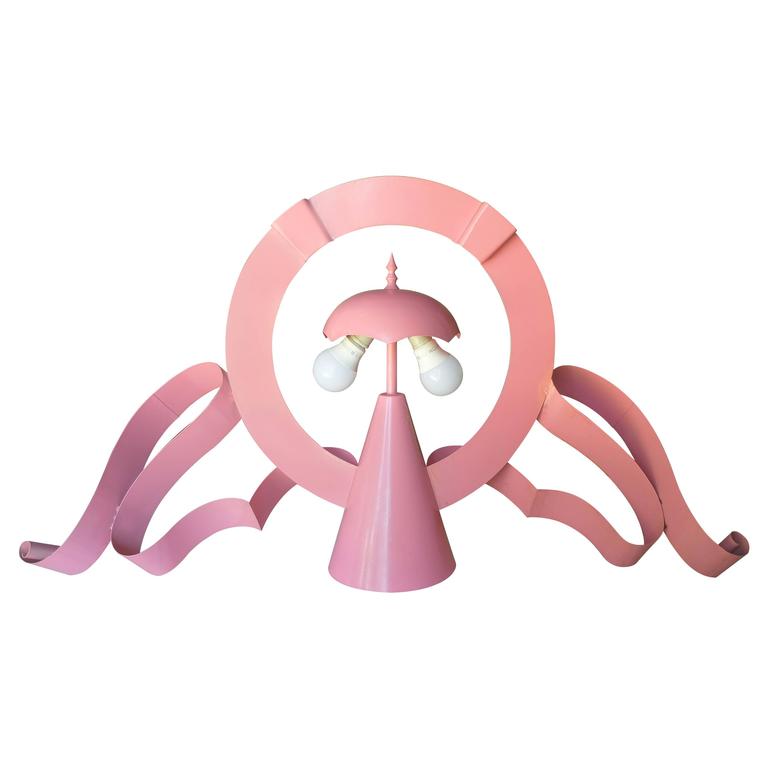

Italian Radical design has not been celebrated in a museum exhibition since a 1972 show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. That changed earlier this month with the opening of “Radical: Italian Design 1965–1985, The Dennis Freedman Collection,” at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where it runs through April 26. On display are 70 pieces of furniture, lighting and architectural models, spanning the period from the movement’s university origins to the early careers of its best-known figures. These include Milanese architect Alessandro Mendini, whose exuberantly patterned late-1970s work with Studio Alchimia countered what was seen as the rigidity of modernism; and Ettore Sottsass, who went on to develop the influential Memphis design collective.

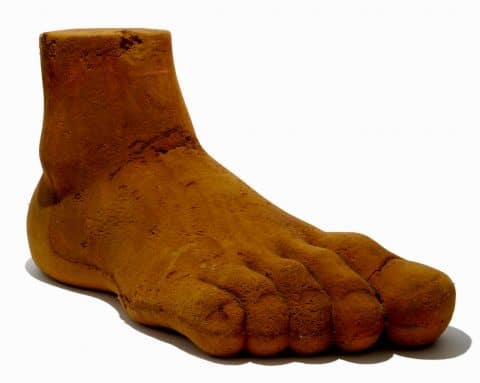

The Pesce UP7 chair, manufactured by C & B Italia, is among the pieces from the Freedman collection included in the Houston show, which runs through April 26. Photo by Kent Pell / © 1969 Gaetano Pesce

The material in the MFAH show — and featured in an accompanying book of the same title — was all collected by one man, Dennis Freedman, the Manhattan-based former creative director of W magazine and Barney’s New York, who had the foresight to aggressively acquire Radical design when it first emerged on the secondary market, beginning in the late 1990s.

Freedman recently chatted with Introspective about the origins of his collection and the message of the Radical design movement beneath its surface appeal.

Gufram released Studio65‘s Baby Lonia — a set of large-scale polyurethane-foam children’s construction blocks — in 1975. In a Q&A in the exhibition catalogue, Studio65’s Franco Audrito explains the blocks’ origins: “After our daughter was born in 1972, we began to think about how children didn’t have instruments to spatially express themselves. Being architects, we thought it would be nice to give our daughter a toy with which she could build. Up to that point, all of our designs were criticizing something. This was the first one we did with a positive goal, to help children express themselves through space manipulation.” Photo by Laboratorio di Pedagogia 1974 / © Gufram archive.

Where did Radical design come from, in philosophical and art-historical terms? Is it related to Pop art?

That’s one of the great misinterpretations of this entire period. There is a Pop art influence, but the emphasis on humor and fun is blown way out of proportion. Radical design was a serious and difficult movement. It was very much a reaction to a bourgeois world that the people involved — the architects and students — no longer believed in. It’s subversive, it’s disruptive, and humor is used to devastating effect. The idea that you would sit on one of the iconic pieces of classical Roman architecture was an attack against the existing conservatism. That’s the fundamental reason I became interested in and then obsessed with collecting works from this period — because of its content, because of the ideas.

In Freedman’s study, a ca. 1969 Gae Aulenti table lamp, a 1969 painted-fiberglass coffee table by Studio Tetrarch and a blue model for Gianni Pettena’s 1967 Rumble sofa — all three included in the Houston show — keep company with a 1970s reclaimed-wood table by José Zanine Caldas, a French Empire-style chair, an Osvaldo Borsani D70 daybed and a 19th-century English side chair. Photo by Stefan Ruiz

Why was Italy the country to spawn this radical work?

The movement grew out of architecture schools. The schools, primarily in Florence, were a hub of political, social and aesthetic conversations. That was unique to Italian culture. Students and faculty formed design collectives like Archizoom and Studio65. The opportunity to make architecture was very rare, so instead, they used these objects to express their ideas.

And why Florence in particular?

Florence is not Milan. It is very conservative. For a young architecture student, living in Florence in the nineteen sixties would be suffocating. You’re elated by living among great buildings that were innovative in their own time, but it’s frustrating. You can’t tear it down, you shouldn’t tear it down, but where else would a twenty-some-year-old student who wants to create feel so constrained and want to break down the walls? Florence! It makes total sense to me.

Studio65’s Capitello, designed in 1971 and produced from about 1972 to 1978 by Gufram, is one of the most iconic pieces of Italian Radical design. Photo by Brad Bridgers / © 1971 Studio65,

Where and when did you begin collecting? What was the first piece you bought?

I happened to be in London in 1998 and walked into Christie’s South Kensington. I opened up a catalogue for a sale of Italian design curated by Simon Andrews, who became my mentor. It was a period I was very much aware of through magazines like Domus and Abitare. There were five or six critical pieces of Italian radical design in that one sale. I was an assistant art director at the time on a modest salary, but I knew there was an opportunity here to build a serious collection. I ended up buying a very early Capitello, which actually went for a high price for the time. I kept thinking, “Who am I bidding against? Someone who wants this piece for their child’s room?” I was living in a one-bedroom apartment in New York City and didn’t realize until after I bought it there was a good chance it wasn’t going to get through the door. It barely squeezed through — there was some give to it — and it took up half my bedroom.

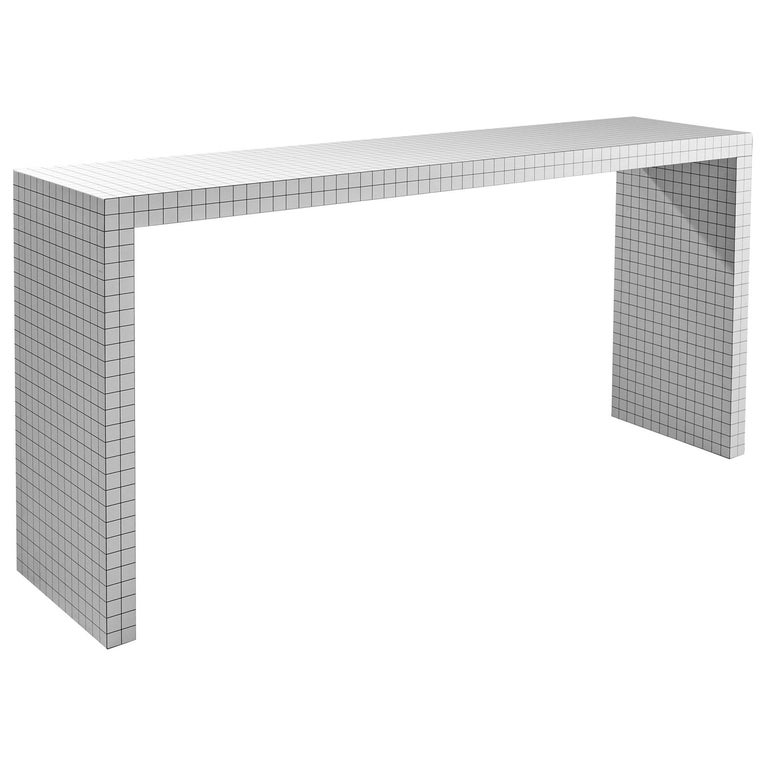

In front of the fireplace in the living room of Freedman’s Manhattan apartment is Piero Gilardi’s 1967 stone-like foam seat Sassi, which matches Capitello in iconic status. To the right of the mantel are additional Italian Radical design pieces: Mendini’s 1974 Monumentino da Casa, Superstudio’s 1970 Quaderna 2600 table and Fabrizio Cocchia’s 1970 Ziggurat lamp. Photo by Stefan Ruiz

Then came a frenzy of collecting activity.

I was very lucky to be in the right place at the right time. People for the most part were not interested. I realized that these rare pieces were in the sales and that the prices were within my budget, so I kept buying. For seven years, I went back and forth to Europe. I bought a great deal from Simon and also in Italy, Austria, Germany and sometimes France. I had to arrange for all the shipping and customs, and somehow managed to get it all to New York. I bought what was once a garage in Long Island, a space built for three cars. It didn’t take long to fill that up, and ultimately, I had to get a warehouse. In twenty years, I sold just one piece to another collector. I never assumed there would be a museum show, but in my own mind, I was curating a collection.

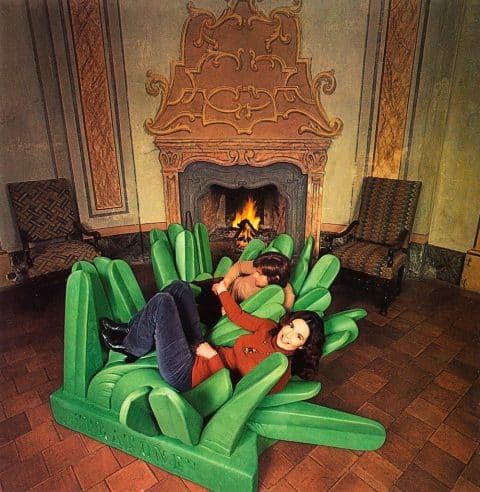

Riccardo Rosso, Pietro Derossi and Giorgio Ceretti designed their foam Pratone (Italian for “big meadow”) seating in 1971, and Gufram produced it in 1986. It, too, is included in the Houston show. Photo by Pratone / © Gufram archive.

What, specifically, did you buy?

I began with Italian design from between 1968 and 1972, concentrating on prototypes and pieces of very small production that were made in the time of their design. Fortunately, they never did large productions of these pieces, so rarity was kind of built in. Then, I became curious about Studio Alchimia, which is even less known than the Radical movement of the late sixties and early seventies.

How has the market changed since then? Can you buy vintage pieces of Italian Radical design today?

When I started, these pieces were just coming on the market. Today, no matter what your budget, it’s not easy to find pieces from the original production. Sassi — the rock — is still being produced. The one I bought was made between 1968 and 1970. If you put an early piece next to one made today, there’s no comparison. Different material, different manufacturing. Many of these pieces are in extraordinarily good condition. The self-skin polyurethane foam develops a patina, almost a crackle surface, like porcelain, that is exquisite. The Capitello in the Houston show has developed a very rich golden patina.

Another exhibition highlight, Andrea Branzi‘s 1985 Cucus chair — from his Domestic Animal series — incorporates tree branches into its painted-MDF form. Photo by Kent Pell / © Studio Branzi

What’s another piece you would point to as an example of something that has more to it than meets the eye?

The Mies lounge armchair and footrest of 1969 by Archizoom, manufactured by Poltronova. Besides being a striking piece of functional sculpture, it was a very reactive piece. At the time, the Italian manufacturers were reissuing the Mies van der Rohe lounge and the Le Corbusier lounge with the pony skin. This was a reaction against the idea that, instead of encouraging new work and dealing with the world of 1969, which was a cataclysmic year, here in Italy they’re still re-making Mies and Corbu. If you have any curiosity about design, how can you not find this piece compelling?

How did the idea for a museum show come about?

It’s always been puzzling to me how rare it is to come across any discussion of this period. I have nothing against Charlotte Perriand or Jean Prouvé, but I can’t count the number of shows their work has been in. You can count on one hand the number of museum shows dealing with this epic period. I have to thank Cindi Strauss, the museum’s Sara and Bill Morgan Curator of Decorative Arts, Craft and Design, and Gary Tinterow, the institution’s director, for bringing this period alive, not just in the exhibition but in the book as well. Cindi did an incredible amount of research, talking to several of the principal figures, and having Germano Celant write an essay, which was really satisfying.

Freedman began collection Italian Radical design in 1998, when he purchased a very early Capitello at Christie’s in London. Photo courtesy of Freedman Studio

Did the Radical design movement lead to anything more mainstream, or did it remain on a trajectory all its own?

It was a time of utopian ideas, idealistic and in some ways unrealistic. The movement came to its logical ending. What came after was from a different place. Avant-garde architects like Mendini were no longer discussing utopian ideals. They were more interested in confronting the issues of “conventional good taste.” They challenged the idea of minimalism and had the audacity to introduce decorative surfaces and pattern. They were interested in the aesthetics of banality. In this way, they too were radical.

As a serious longtime collector, do you perceive a thread underlying what you buy?

No matter what I collect, the fundamental conceptual ideas are very important. But if they don’t resolve in something poetic, I’m not interested.