October 21, 2018A new exhibition explores the fun side of the mid-century work of 40 American designers. Here, Ray Eames stands with the first prototype of the Toy, 1950. Top: A 1952 publicity photo of Charles and Ray Eames’s House of Cards deck for Tigrett Enterprises. Photos courtesy of © Eames Office LLC

In the past decade or so, mid-century modern has gone from an obsession of design cognoscenti to a style the proverbial man in the street easily recognizes. It is, arguably, as defining a look today as it was when Knoll and Herman Miller first introduced progressive-minded consumers to pieces by Eero Saarinen, George Nelson and Harry Bertoia in the years following World War II. So, there might seem little left to illumine about the aesthetic. But it’s a long way from Charles and Ray Eames to West Elm. And as “Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America” makes clear, there’s always something new to consider even about a sensibility we know and love so well.

Organized by the Milwaukee Art Museum — where it is on view through January 6 — and the Denver Art Museum (May 5 through August 25, 2019), the exhibition takes a thematic approach to this now-classic period of American innovation, highlighting, in the output of more than 40 designers and architects, a spunkiness and vivacity that is easily overlooked now that these products for the home have found their way onto the pedestal.

Rendering of Douglas and Maggie Baylis’s Freeway play project, ca. 1964. Image courtesy of the Environmental Design Archives, University of California, Berkeley

A sense of fun is apparent in such familiar pieces as George Nelson’s Marshmallow sofa, but “Serious Play” looks beyond the finished product. “Several designers of the period acknowledged that one of the best ways of solving a design problem is to allow for time and space to play,” notes Monica Obniski, the Milwaukee Art Museum curator who, along with Denver Art Museum curator Darrin Alfred, co-organized the exhibition. “For figures such as Ray Eames or Alexander Girard, cutting colored paper into interesting shapes and rearranging objects on a storage wall were activities that, seemingly, had nothing to do with their more serious work — designing a line of furniture for Herman Miller, say, or a new interiors project for a client — but provided creative outlets that led to more interesting design solutions.”

Another such outlet was provided by certain corporations, which hired designers to create imaginative advertising campaigns. Paul Rand’s colorful cutout-like images for El Producto cigars, for example, were the playful antithesis of the fat man and his stogie.

Organized around three themes — the American home, child’s play and corporate approaches to design — the exhibition contains such objects as Eero Saarinen’s body-hugging Womb chair, Richard Shultz’s Petal table and the irregularly geometrical Eames storage units (ESUs), as well as work by less familiar designers like Henry P. Glass (represented by a child’s bedroom set) and Estelle and Erwine Laverne, among whose creations are sculptural floor lamps emblazoned with doll-like characters.

Postwar affluence (tempered by Cold War worries), advanced manufacturing technologies, the development of new materials and a space-age taste for the new all propelled the spread of modern design in the 1950s and ’6os. “Americans acquired more goods for their homes, and self-expression through the choice and placement of objects became central to the individualization of the home,” observes Obniski. “Working for George Nelson Associates, Irving Harper designed some of the most important, recognizable and playful clocks of the twentieth century for the Howard Miller Clock Company. Decorating playfully was one approach that countered a homogenous mass-consumer culture and parallels what we observe in today’s domestic decorating culture.”

Isamu Noguchi models for play equipment, 1965–68. Photos courtesy of the Noguchi Museum, New York

Irving Harper Paddle clock for Howard Miller Clock Company, 1957. Photographs by John R. Glembin

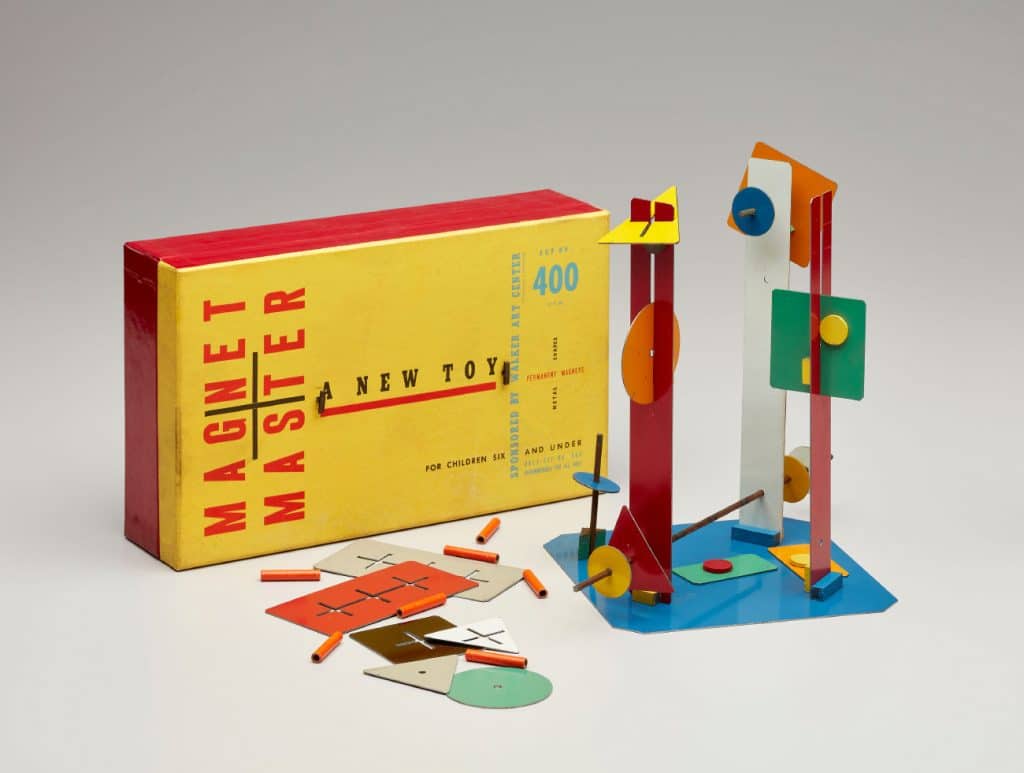

The vogue wasn’t limited to adult spaces. “Designing for children was serious business during the postwar period,” says Obniski. “Educational toys that were designed well and taught good design principles were prized. Several architects and designers, including Anne Tyng, created toys that were marketed as a way to develop young creative minds.” Tyng — architect Louis Kahn’s longtime collaborator — created an inventive construction that could be manipulated into various forms, including a chair, rocking horse and desk. For sheer fun and visual sophistication, there’s Gloria Caranica‘s Rocking Beauty hobby horse, which reads like a minimalist sculpture with a sense of humor. And the designers’ attention to a child’s material world wasn’t focused solely on playthings. Eva Zeisel’s Wee Modern porcelain tableware for Goss China — decorated with crayon-drawing-like imagery — is noteworthy for its free-flowing ergonomics tailored to a little one’s manual dexterity.

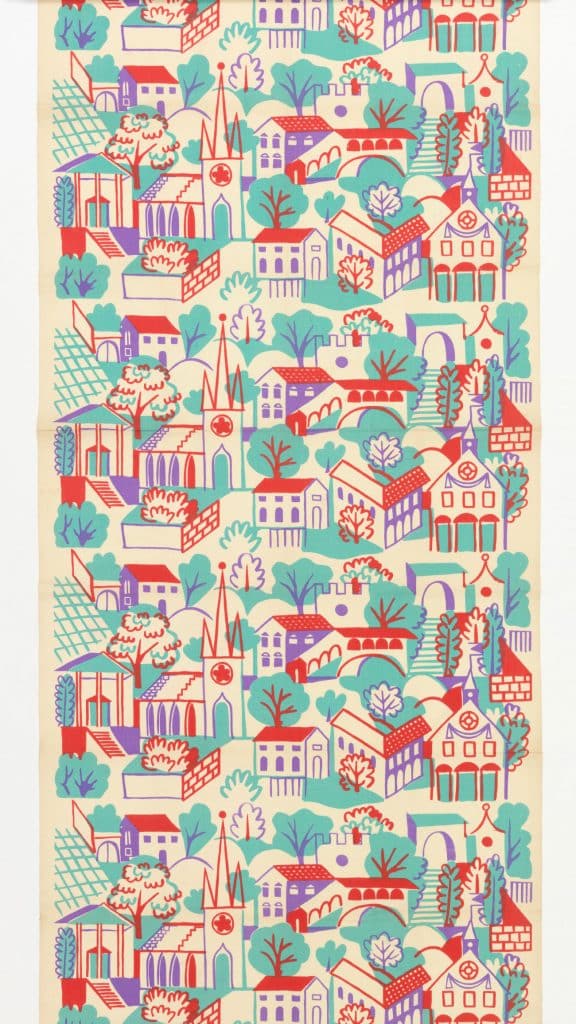

Shedding light on process is a central ambition of the show, and “Serious Play” includes a number of materials that document the evolution of a design. Alexander Girard — director of design for Herman Miller’s textile division — brought a new dynamism to all sorts of products, from wallpaper to furniture. The exhibition contains several of his prototypes for a wooden tray table incorporating silkscreened textiles in various geometric patterns. Also on view are drawings and prototypes of game tables done by Gene Tepper for the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa). Beginning in 1956, Alcoa reached out to a number of designers — including Girard and Isamu Noguchi — to create speculative works for its Forecast program, a public relations campaign touting the merits of its products. Most of these pieces were never realized, but the exhibition does include two of Noguchi’s small origami-like aluminum tables.

Compared with what one might call the Humorless Toil of high modernism (and its strong whiff of social engineering), mid-century American design generally operated on a more humane and optimistic plane. Although its practitioners were certainly committed in their exploration of form and function, their program was more celebratory than prescriptive. In the years since, the market and museums have, perhaps, obscured that fact. “Serious Play” sets us straight.