March 20, 2013Stonehouse (1986), the summer retreat of the Austrian architect Günther Domenig — who was known for creating buildings that looked “inside-out” — features in The Architect’s Home, which spotlights the houses that notable architects built for themselves. All images courtesy of Taschen. Top: For his L-shaped residence (1961–62) north of Madrid, which includes a basement office, Francisco de Asís Cabrero Torres-Quevedo used many of the materials — steel, glass and brick — that he employed in his most notable buildings.

I strongly disagree with the opening sentence of The Architect’s Home, a formidable and excellent book first published in 2008, with an updated reprint released this month (Taschen, $40). Gennaro Postiglione begins his text with, “Because of its private and intimate character, the interior has not received much attention.”

As anyone who uses 1stdibs, subscribes to Architectural Digest or watches HGTV knows, that’s not quite true, at least not anymore. But Postiglione, a professor and the editor of Area magazine, both comes from and examines the highbrow European tradition of architecture, in which the outsides of buildings have received more attention than the insides.

The Architect’s Home is not a coffee table book; it aspires to shelf space in an intelligent library. A project of the Modern European Architecture-Museum Network at the Polytechnic University of Milan, Postiglione’s book, presented with extensive contributions by four other writers, is academic but by no means joyless. There is attractive color photography to break up the comprehensive text, and the writing is alive to the pleasures of great design. The result is a thick, encyclopedic volume with the cool authority of a whooshing, ultramodern train in some Swiss city.

No less than 100 houses are featured and dissected, all lived in and designed by European architects, only about 10 of whom will be familiar to the casual American reader. You may not have heard of Günther Domenig, but now you can see a photograph of his chic guest bathroom and a longitudinal section drawing of his appealingly angular Austrian home.

The central idea is that architects’ houses matter because they further our understanding of each practitioner in a unique way — what better way to grasp someone’s most deeply held principles and priorities than by seeing the space he or she designed as his or her own home?

Sarah Wigglesworth and Jeremy Till built their north London Straw House (1998–2001) from wood, steel, concrete, rubble, corrugated metal, sandbags and plastic.

For one thing, the book demonstrates that architects’ residences are generally more austere than your average dwelling — but then again most of the people in the book are creatures of 20th-century modernism. Predictably, notable minimalist John Pawson’s home in the Notting Hill section of London is cloaked in stark white cabinetry (behind which, presumably, hides the messy detritus of contemporary life, piled up and on the verge of bursting through the doors).

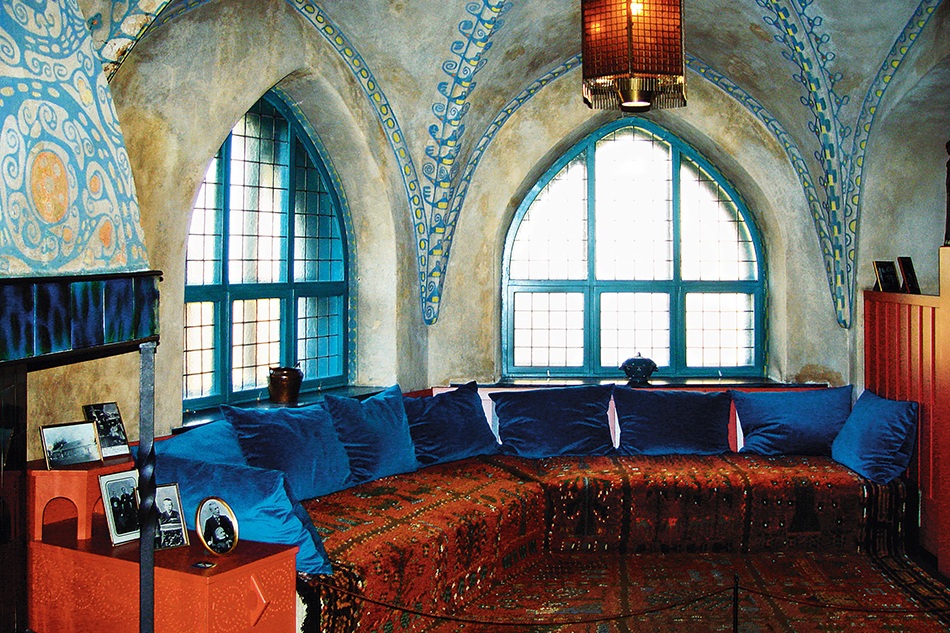

But the Kentish 19th-century country house of William Morris, the Arts & Crafts legend, is perhaps less pattern-covered and cozy than one would imagine. An image of the elevation, plans and section of Red House, as Morris called his retreat, is exquisite to behold, and appears to have been delicately rendered in gouache or watercolor.

This year, because of an upcoming retrospective of his work at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Le Corbusier is in the news, so some readers will immediately flip to the chapter on the Swiss master’s Paris apartment (slideshow above). The tiny roof-garden kiosk, with a chunky, cantilevered slab roof, is so echt Corbusier (both elegant and brutal) that it delivers an immediate jolt of pleasure.

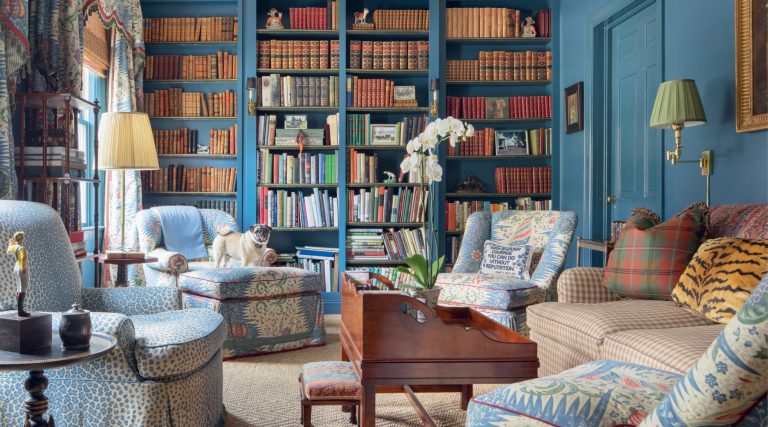

Plenty of discoveries abound here for any reader. For me, it was the work of British architect Michael Wilford, who neatly balances a certain exuberance (purple couches and some Gehry-esque volumes) with restrained modernism in the East Sussex, England, house he built in 2000.

Ultimately, The Architect’s Home has preservation and conservation on its mind, and it’s hard to argue with those goals. By providing a taxonomy of structures worthy of study, it elevates some of the lesser-known examples and shines a light on excellence that could easily be erased by a wrecking ball. It is a well-observed record that expands our consciousness, and thus belongs on anyone’s list of essential architecture books.

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore