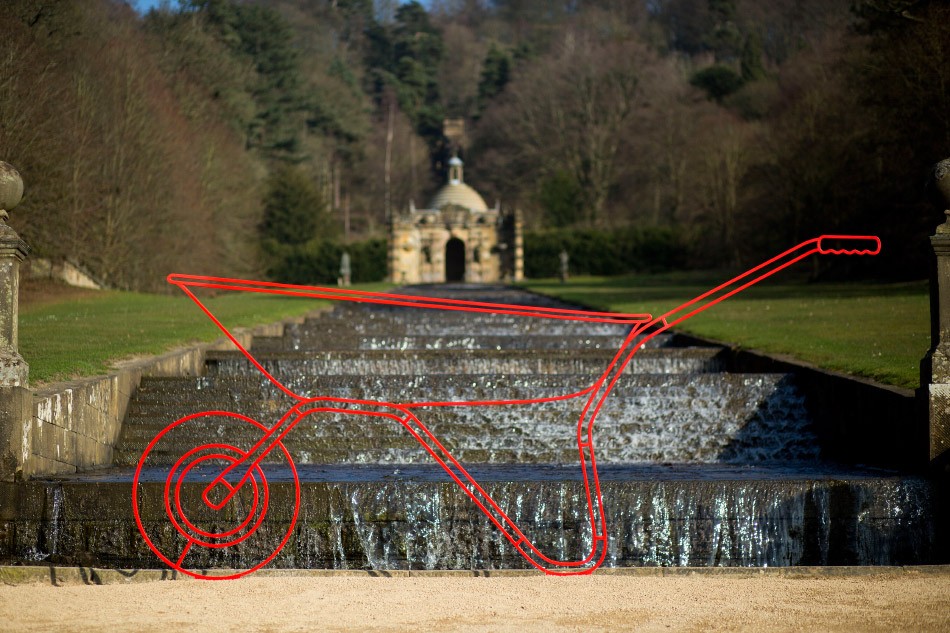

June 11, 2014Peregrine Cavendish, the 12th Duke of Devonshire (photo by David Vintiner) has been collecting art since his 20s and today serves as the deputy chairman of Sotheby’s. Top: Chatsworth has been home to the Cavendish family since 1549. All photos courtesy of the Devonshire Collection, Chatsworth, by permission of the Chatsworth Settlement Trustees

Peregrine Cavendish, the 12th Duke of Devonshire, could have quietly settled in after inheriting Chatsworth, one of Britain’s grandest heritage houses, in 2004. Instead, he has turned the 35,000-acre estate — famous for its collection of Old Masters — into a vibrant center for contemporary sculpture and art. As the deputy chairman of Sotheby’s, the Duke, who has been steadily collecting art since his 20s, first hosted Sotheby’s annual “Beyond Limits” exhibition on Chatsworth’s grounds in 2006, with monumental sculptures by such 20th-century and contemporary artists as Robert Indiana, Damien Hirst and Marc Quinn dotting the expansive park.

“Mostly people were very enthusiastic about the exhibition,” the Duke recollects, “Although we had some letters complaining: One person said he came for peace and quiet, not to be challenged.” (The London art world didn’t initially make the journey, says the Duke, who imagines they likened Chatsworth, in Derbyshire, a two-hour train ride from London, to “Ulan Bator.”)

Today, Chatsworth is a must-visit art destination, thanks in part to the Duke’s passion for seeking out new talent and an exciting year-round exhibition schedule. (A Michael Craig-Martin show is currently on view.) On June 16, 1stdibs is sponsoring a talk between the Duke and Rosalind Savill, the former director of London’s Wallace Collection. Here, he gives Introspective a preview of the event, discusses the origins of his interest in art, why he decided to use Chatsworth as a canvas for contemporary work and what he would buy for a million pounds.

Chatsworth houses some 3,000 Old Master paintings.

1. Growing up, were you very aware of your family collection and was a sense of responsibility toward it inculcated in you?

We didn’t move to Chatsworth until I was 13, and even then, I don’t remember being really aware of the heritage. The artwork that had the strongest influence on me wasn’t an Old Master; it was the painting done of my mother by Lucian Freud. She was 37 or 38 and very good-looking, but the painting made her look much older. My parents’ friends were upset, but [my parents] had the confidence not to worry. It taught me that you mustn’t worry about what other people think or say about art.

I bought a little David Hockney drawing in my early 20s. Not many of my friends were interested in art, but when I met my wife, Amanda, she was. Her mother was collecting in the 1930s — not much, because she didn’t have a lot of money, but she bought Picasso and Matisse. So Amanda was used to that, and when we got married — we were only 23 — that was already part of our life.

2. After “Beyond Limits,” how did you grow into presenting your own exhibitions, like those on the British sculptors William Turnbull and Anthony Caro?

Once we were at Chatsworth and had this big canvas, it seemed natural somehow. We have a wonderful team, headed by Matthew Hirst, who is head of collections, and his colleague Hannah Obee, who is in charge of exhibitions. We meet to talk about the program, and we always have more ideas than time. Sometimes we have as many as seven exhibitions in the year. For the last four years, we’ve had a new gallery — three rooms and a decent passage — to show work inside on a small scale. At the moment, we have a brilliant exhibition that Hannah has done about people who lived on the estate and went away to the war. We usually have a spring outdoor exhibition, like the Turnbull or Caro. We are talking to lots of artists at the moment.

The current Duke, who has a particular passion for collecting ceramics, previously displayed the 23 porcelain vessels of Pippin Drysdale’s Kimberley Series 2, 2008, at Chatsworth.

3. How do you feel about integrating contemporary pieces into a home filled with antique treasures?

I don’t really worry about it. A lot of it is experiment. I’m thinking about a Pippin Drysdale ceramic exhibition and putting this contemporary work on two 18th-century Boule tables. They are in the music room, where they’ve been ever since they arrived around 1715. I don’t think we have ever acquired things with a particular place in mind, but we try to put pieces on the visitor route for at least a year so that people can see them. I think it’s really crucial to keep stuff moving around — it’s fun and interesting.

The acquisitions that the Chatsworth House Trust makes — as opposed to our personal acquisitions — must be visible on visitor routes or in storage; they can’t be in our private bit of the house. The trust has an acquisitions fund, and it’s all done very carefully and correctly. [The trust] has added historic paintings to the collection, but we also buy other things. We recently bought one of the first leather fire buckets, which I suppose has a didactic purpose — to teach people about how fires were dealt with. Houses like this would have had hundreds of them kept at the ready. This one has a coronet on it. I’m all for a bit of bling — it cheers things up.

David Hockney’s Le Parc Des Sources, Vichy, 1970, was the Duke and Duchess’s first important art purchase.

4. What is your approach when it comes to your personal collection? Are you purely governed by your tastes, or do you take a longer view with regard to value?

I am not at all systematic about collecting; it’s simply what I like. For me now, it’s mostly about ceramics, although I did buy an Edward Burroughs painting last week that is really beautiful. I particularly like Harry Epworth Allen, but he has become quite expensive now, which applies to an awful lot of art. The first big picture that my wife and I bought, in 1970, was a Hockney. Even then it was a stretch; now it would be seven figures, impossible. But you have to adjust; I have no problem with that.

5. What would you buy now for £10,000? For £1 million?

If I had £10,000, I would buy ceramics by Natasha Daintry, a wonderful artist who makes things in lovely bright colors. We have one piece by her; it’s like a box of sweets. If I had a million, I would get a painting by Peter Doig. I thought his show at the Tate was incredibly interesting and beautiful and odd. I’d love to hang something by him alongside the Old Masters.

Early in their courtship, the Duke and Duchess discovered they shared a passion for collecting. Here, they’re photographed with Marc Quinn’s Spiral of the Galaxy, 2013.