Most people who buy art do so with at least one eye on its value as an investment. But to maintain their value, artworks of all kinds, from charcoals to pickled sharks, require a deliberate approach to storage and preservation. NFTs are no different.

However uncertain the future may feel in 2022, one safe bet — perhaps the only one left — is that technology will continue to advance along an exponential curve. What does that mean for the long-term prospects of an art form that relies on technology, not just for storage and display but for its very essence?

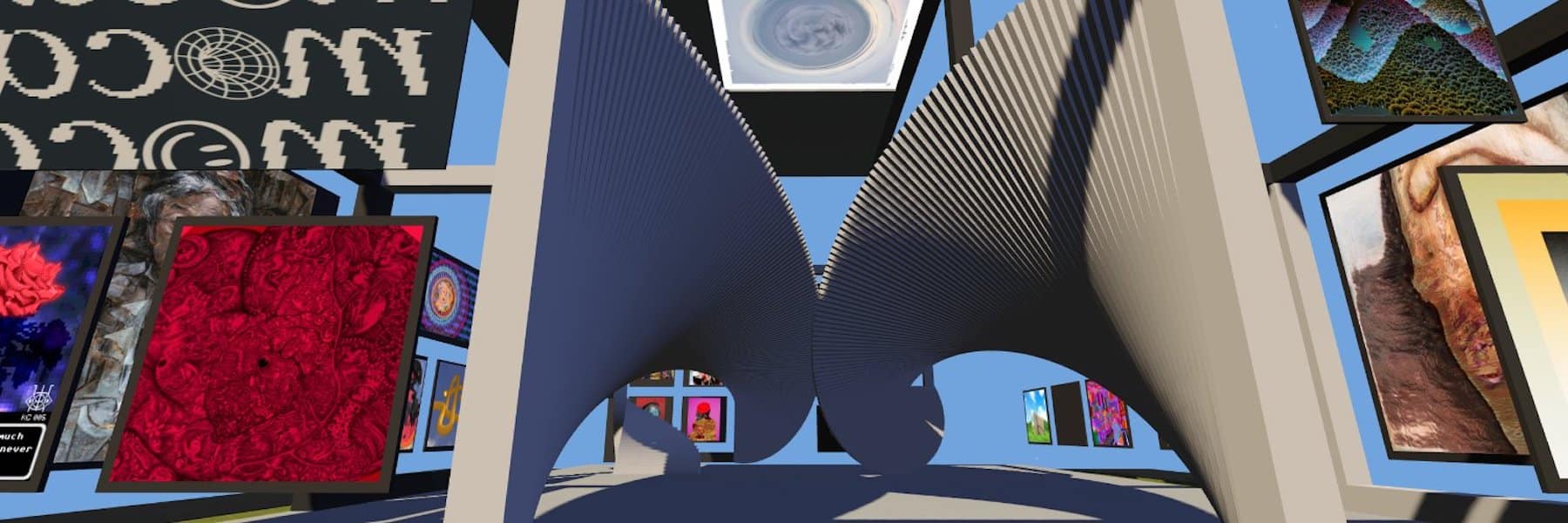

For NFT evangelists like Colborn Bell, founder of the Museum of Crypto Art (M○C△), the resilience of the blockchain is an article of faith. The museum’s permanent Genesis Collection is a time capsule of NFTs produced between 2017 and 2020. Comprising donations from more than 20 collectors, it features extremely valuable works that, according to the M○C△ Foundation’s guidelines, can never be sold.

Bell’s motivation in establishing the museum derives from his belief that the advent of NFTs represents an inflection point in art history. Its purpose is to provide to future generations a snapshot of NFT culture at the dawn of this new age. Key to the project is an understanding of the blockchain as a permanent record.

“Ethereum,” Bell says, “acts as an immutable ledger. Using it, we’ll be able to trace all of these very abstract ideas of value transfers, the networks that were formed, and prove the philosophy and the power of crypto art.”

Bell holds the view, quite common among crypto ultras, that the image — the MP4 video or JPEG — attached to the token is secondary, and the record on the blockchain showing the intent of the market, the transactions between various collectors arriving at a determination of value, is the artwork’s true core.

“We live in a very visual society, but I think we’re trending toward a kind of machine-learning transhumanist society,” he says. The blockchain ledger, crucially, provides a measure of value that will be legible to future AIs. It goes without saying that Bell also has faith that as technology changes, the blockchain will be accommodated. “It’s obviously entirely possible that quantum computing comes along and breaks every hash and security that we have today,” he says. “Although you would imagine in that future that there would be some equivalent security.”

Some professional art conservators regard these kinds of assurances as a little hand-wavy and unrealistic. Regina Harsanyi is one such conservator working in time-based media, a category that includes video and sound installations as well as digital art and, now, NFTs. “Storage is not preservation,” Harsanyi says, meaning that although you might well be able to store a piece of NFT cryptoart, changes in technology could render it functionally inaccessible.

“The token ID of a particular work pulls up a URL. And that URL is not on chain. That URL is on a server somewhere else,” she explains. So, however durable the blockchain proves to be, the unwary collector might end up holding a link that goes nowhere.

“Even if it points to a distributed storage protocol URL, a lot of these platforms have the IPFS [Interplanetary File System] pointing to a gateway, and that link is incredibly fragile,” Harsanyi adds. “Because if that company ever stops paying for the gateway, that link is going to rot.”

You might object that conservators have to think about deterioration — that is literally their job. In fact, many artists in the field are already making these considerations integral to their work.

John F. Simon Jr. is a veteran of digital art whose early pieces from the 1990s involved coding specialized drawing tools for the Mac. As such, he is used to obsolescence as a feature of the digital environment. “I have an old Quadra,” he says, referring to the Quadra 800, a short-lived Apple desktop from 1993–94, “and when I need one of those tools, I fire up the Quadra and find some way to get the code out of there on a floppy disk.”

Since 1997, Simon has been producing versions of a work titled Every Icon, exploring every combination of black and white squares in a 32-by-32 grid. The most recent edition has been encoded entirely on-chain, with individual instances minted as NFTs, creating a more robust structure that requires fewer vulnerable links. It’s a more expensive approach, but one that he believes will be more durable long-term.

Richard Garet, who has also been working in multimedia for decades, describes the limitations of NFTs as “site-specific,” where the site just happens to be digital. Garet’s NFT corpus (including 30 pieces minted on 1stDibs) has been produced to fit the platform in terms of file size, resolution and aspect ratio.

“What you see is what you get,” he says. While an approach like this does not guarantee the integrity of the links, it does at least offer the assurance that the work on screen contains the entirety of the artist’s intent.

Anne Spalter is both a digital artist herself and a cofounder, with her husband, of the Anne + Michael Spalter Digital Art Collection, one of the largest collections of its kind in the world. It includes NFTs as well as some of the earliest computer-based pieces, dating back to the 1960s, by artists like Manfred Mohr and Vera Molnár. The Spalters’ curation of their collection reflects their appreciation of NFTs as part of that continuum.

Their selections are guided by some very practical criteria. The Spalters don’t, for instance, buy art that requires computation. “We try to collect work that doesn’t have that kind of intensive archival challenge, because we’re not a museum and we don’t have any staff,” Anne says. As a means of future-proofing her own pieces, she is happy to provide a buyer with a USB including an uncompressed file, in anticipation of a time when files of this complexity can be shown without compression.

And for NFT works she acquires, she takes a belt-and-braces approach to storage. “I think collectors can be a bit proactive,” she says. “To me, it’s not that different from if I collected an image or a digital video from someone and they gave me a paper certificate of authenticity. I have the token as a certificate of authenticity, but I also have the digital file because I’ve downloaded it and backed it up. So, if it gets unpointed to, it could be repointed to, or I could just say I have the token. But I also have the file, so I can always show it.”

The Spalter Collection points the way for assuring the long-term viability of digital works as valuable cultural products. If you’re interested in buying NFTs as anything other than speculative financial vehicles, it could be that a pragmatic approach like this is also the safest.