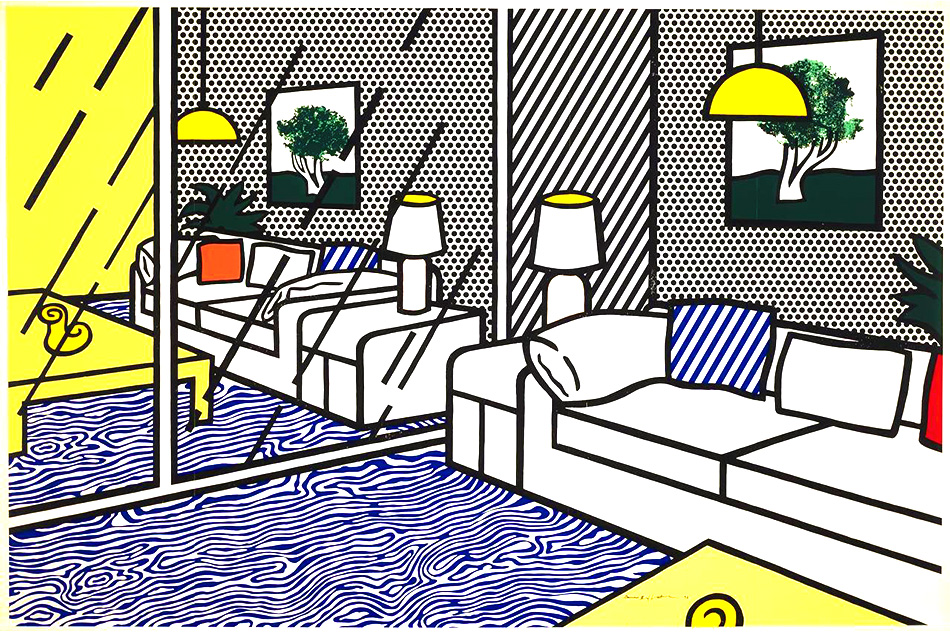

March 7, 2016In the lithograph Cicada, 1981, Jasper Johns deployed the famously exaggerated crosshatch pattern that appears in his works across mediums. The print is available through Susan Sheehan Gallery, one of the many members of the International Fine Print Dealers Association (IFPDA), who can now be easily found on 1stdibs in their own dedicated category.

By the time composer and visual artist John Cage set sheets of newspaper aflame to create his ethereal “fire prints” in the 1980s, printmaking had already proved itself a wildly experimental terrain for many young artists of the vanguard. The explosion of interest in printmaking in the 1960s — led by such artists as Jasper Johns, Robert Motherwell and Robert Rauschenberg — radically shifted perceptions of the medium and demonstrated its dynamic potential for artistic innovation. “The moment was full of so much energy. It really got rid of some of the cobwebs of the print world,” recalls London’s Bernard Jacobson, who began dealing in prints in 1969.

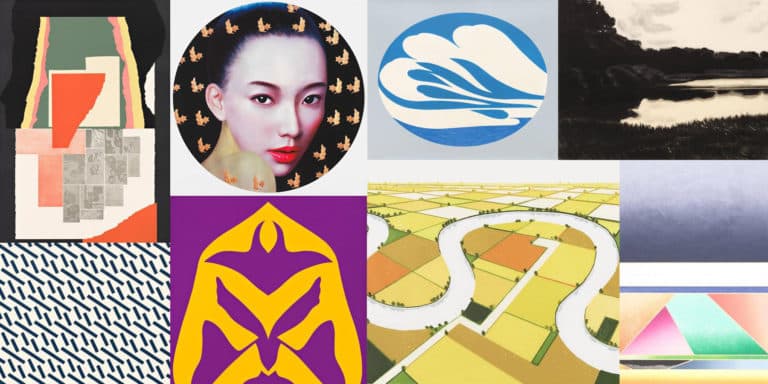

Pursued in the 1960s and ’70s largely by Pop artists drawn to its associations with mass production, advertising, packaging and seriality, as well as those challenging the primacy of the Abstract Expressionist brushstroke, printmaking was embraced in the 1980s by painters and conceptual artists, ranging from David Salle and Elizabeth Murray to Adrian Piper and Sherrie Levine. By the end of that decade, dozens of well-known artists had fully integrated printmaking into their practices. Yet despite its popularity among the art world’s elite, certain misconceptions plagued printmaking, which many still viewed as a mere tool of rapid reproduction. It was then that five savvy art dealers enamored of the medium recognized the need to do something. In 1987, led by legendary print specialists Sylvan Cole and Mary Ryan, this quintet founded the International Fine Print Dealers Association (IFPDA).

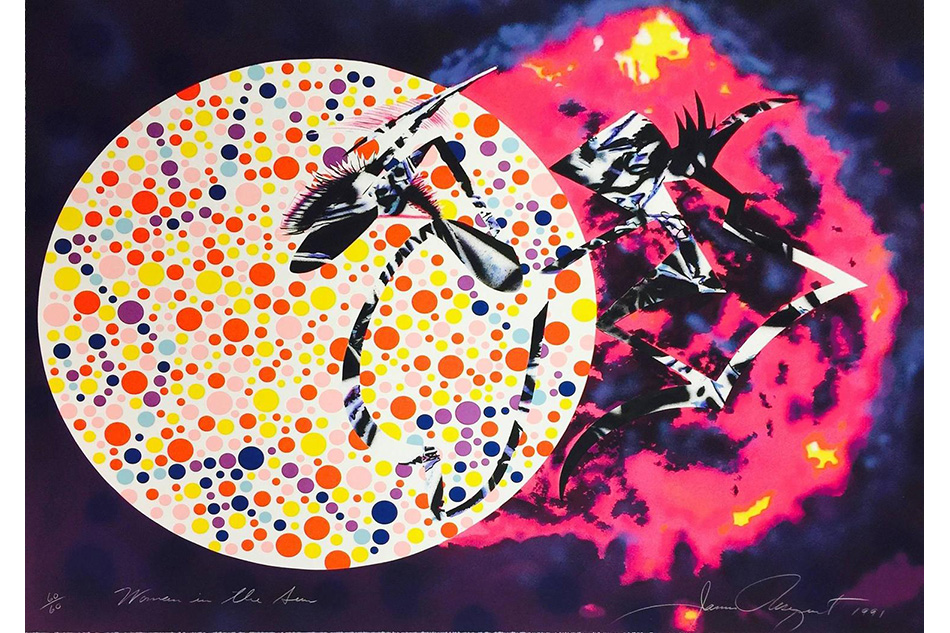

Before the Rain, 2015, a screen-print by British painter James Nares, offered by Senior & Shopmaker Gallery

“These dealers realized that many people didn’t understand that prints were original works of art and not merely photomechanical reproductions, so they formed an organization of vetted members who were committed to educating and expanding awareness,” says Michele Senecal, the IFPDA’s executive director. The association has since expanded to include more than 160 international members, ranging from Old Master specialists to esteemed contemporary publishers. (Many of them are represented on 1stdibs through a new dedicated search.)

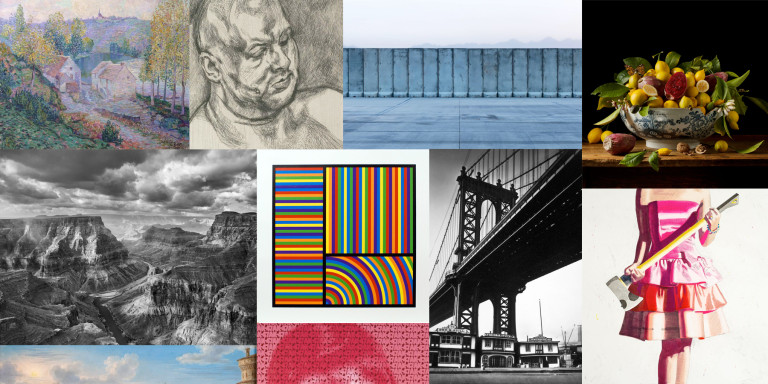

The launch, in 1991, of the annual IFPDA Print Fair in New York is among the organization’s primary achievements. The only major fair dedicated to fine-art prints, it’s known as a serious destination for connoisseurs, collectors and museum curators on the hunt for historical gems as well as brand-new editions by contemporary artists. “The aisles are now full of art lovers, not just print lovers,” says Jacobson, confirming that the event, held every November at the Park Avenue Armory, has been hugely successful in spreading an appreciation for editions and multiples. The association has also worked hard to shed light on the dynamism and importance of printmaking by providing grants for exhibitions and publications. The Baltimore Museum of Art, New York University’s Grey Art Gallery and the Morgan Library and Museum are among the institutions receiving IFPDA funding for print exhibitions this year.

The fact of the matter is, however, that people have good reason for confusing fine-art prints with their more commercial counterparts. The differences aren’t immediately apparent and the typologies may not be entirely clear to the average person, or even to those who collect in other categories. After all, our closest connection to the printed image is through mass-produced newspapers, magazines and books, and many people don’t realize that even though prints are editions, they start with an original image created by an artist with the intent of reproducing it in a small batch. “It’s another tool in the artist’s toolbox, just like painting or sculpture or anything else that an artist uses in the service of mark making or expressing him- or herself,” says IFDPA vice president Betsy Senior, of New York’s Senior & Shopmaker Gallery, which specializes in works on paper, including prints, by major American and European artists.

The IFPDA Print Fair, held every November at New York’s Park Avenue Armory, saw record attendance last year. “The aisles are now full of art lovers, not just print lovers,” notes London dealer Bernard Jacobson. Photo © Sari Goodfriend Photography

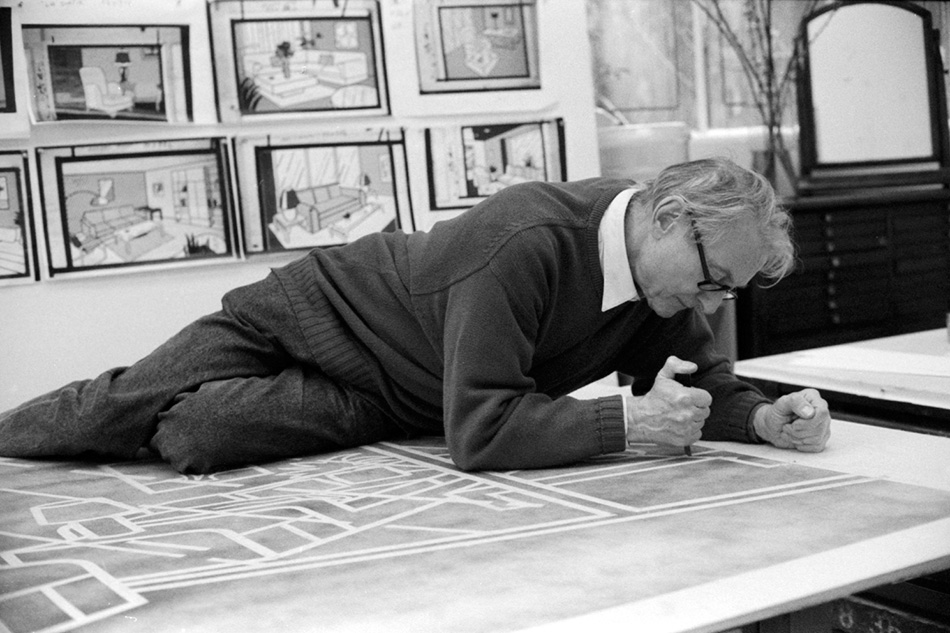

Robert Gober, known for his surreal sculptures, works on a two-dimensional piece in 2002. Photo © Sidney B. Felsen

In the simplest terms, printmaking is the transfer of an image from one surface to another. An artist takes a material like stone, metal, wood or wax, carves, incises, draws or otherwise marks it with an image, inks or paints it and then transfers the image to a piece of paper or other material. “No one would ever look at a Rodin bronze and say it wasn’t original, even though it’s not unique,” says print specialist Lyndsey Ingram, of London gallery Sims Reed, pointing out that the French sculptor created his own molds, which were then cast. “But somehow many people don’t realize that prints are original and often have a texture and quality that you can’t achieve in other mediums — even painting or drawing.”

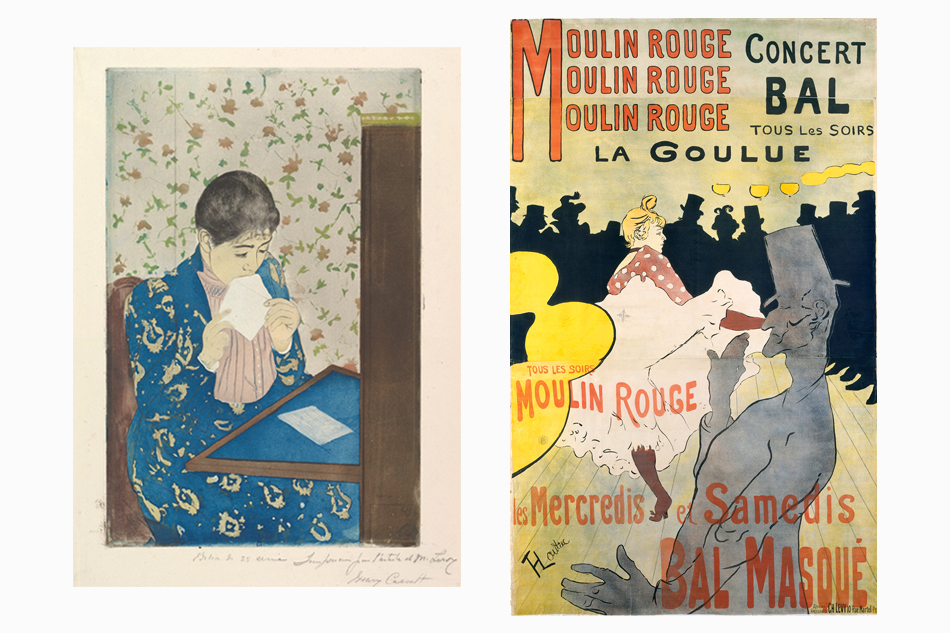

According to Senior, the misunderstanding stems, in part, from the idea that a print “is just copied from a painting by some reproductive means and then mass-produced.” Although there certainly have been print artists who have reproduced existing images (Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s celebrated lithographic posters, for instance, were made in 100-plus editions), fine-art prints are created in strictly limited editions — of 20 or 30 or maybe 50 — and are always based on an image created specifically to be made into an edition.

Because an artist’s editions tend to be more affordable and available than his or her unique works, new collectors are often directed toward prints as a starting point. “I love the idea that they are more accessible. So much art today is far removed from people who really love art,” says Jacobson, drawing a contrast with the trophy hunters and speculators operating at the high end of the art market.

Accessibility does not mean prints appreciate at a different pace from other mediums. “The print market increases parallel to the paintings market,” Ingram explains. “And in some ways, value is more easily determined because there is more than one of them out there.”

History Kids, 2013, a silkscreen by Ed Ruscha, offered by London’s Sims Reed

Indeed, because prints are multiples, says Diana Burroughs, director of New York–based Marlborough Graphics, “the print market is far less volatile than the painting market. One generally sees a gradual increase in a print’s value over time, especially as the edition sells out.”

But price is not the only practical reason to embrace the medium. Prints are often a more feasible way of acquiring works by an artist you love but who tends to create objects you could never house. “How many of us are going to be able to put a Richard Serra sculpture on our front lawn?” asks Senecal. “But what he does in his printmaking is so tactile and so evocative of his work as a sculptor, and his prints are on a scale that fits in a home. It’s an opportunity to own something by one of the great artists of our time.”

One challenge in advising new collectors to buy prints is that it is a sophisticated medium, points out Ryan Cross, associate director of Boston’s Barbara Krakow Gallery, and to understand it, one needs to master quite a bit of technical terminology. Some collectors seek out prints precisely because they are drawn to those complex processes and like to “geek out,” as Cross puts it, on the technical aspect. That said, “you don’t have to know everything about printmaking before buying a print,” notes Senecal. “People often ask me what types of prints they should collect — etchings or woodcuts or linocuts or silkscreens or lithographs or whatever. But it’s really more how the artist used those processes and what he or she was trying to express through the medium.” (See the definitions of printmaking terms in “The Definitive Guide to Printmaking Techniques” on The Study.)

“How many of us are going to be able to put a Richard Serra sculpture on our front lawn? But what he does in his printmaking is so tactile and so evocative of his work as a sculptor, and his prints are on a scale that fits in a home.”

Frank Stella’s Extracts — Moby Dick Deckle Edges Series, 1993, offered by Denis Bloch, involves multiple printmaking techniques on dome-shaped plates.

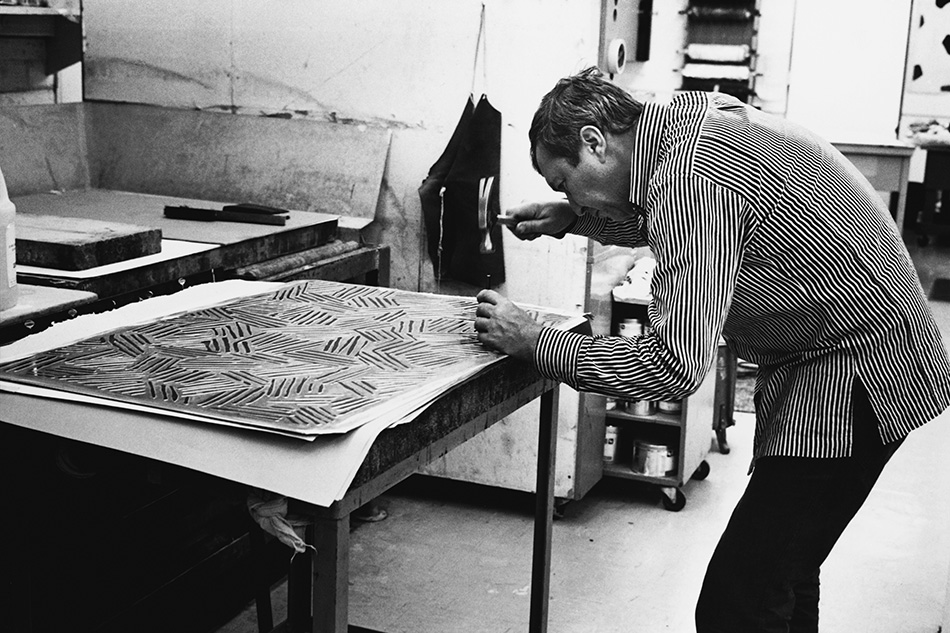

Those processes, which can be far more complicated than painting, usually involve an intimate collaboration with a master printer, an expert who advises the artist on the technology and provides the elaborate equipment required. “Some of the best prints come from a wonderful synergy between artist and printer,” says Senior, pointing to Serra’s work with Gemini G.E.L., in Los Angeles. But the idea that an artist has collaborated with someone outside his or her studio to create a work can also be confusing to new collectors.

“When people hear the term ‘master printer,’ they think the artist didn’t make the work, even if you’re talking about someone really dedicated to printmaking, like Sol LeWitt,” says Cross. Insiders, however, including generations of revered postwar and contemporary artists in the U.S. and Europe, know that without an expert printer and the machinery and tools available in a print workshop, many of these seminal artistic experiments would not be possible. Just consider Frank Stella’s 1993 “Moby Dick” series, printed on dome-shaped plates by his longtime collaborator, master printer Ken Tyler at Gemini.

Groundbreaking print studios like Gemini began to crop up in the mid-20th century. These included Tamarind, first founded as a lithography shop in Los Angeles; ULAE on New York’s Long Island; and Crown Point Press in San Francisco. The timing was due to the fact that many artists had developed a taste for printmaking during the Great Depression via the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which opened print shops for unemployed artists to help create useful and uplifting messages that could be widely disseminated. “After the WPA, in the 1940s, there was a sort of void, because there had been access to lithography stones and presses but then those shops closed,” explains Shelley Langdale, associate curator of prints and drawings at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which is shining a light on experimental approaches to printmaking in the mid-century with “Breaking Ground: Printmaking in the U.S., 1940–1960,” on view from March 26 through July 24.

Twosome, 2005, a drypoint by Louise Bourgeois, offered by Marlborough Graphics

Then the radical British printmaker Stanley William Hayter fled war-torn Europe in the ’40s, abandoning his cutting-edge Paris print workshop, Atelier 17, for New York, where he brought such artists as Louise Bourgeois and Jackson Pollock into his studio. “He was incredibly influential,” Langdale says, “and incredibly innovative, making unique impressions and layering screen-prints on top of intaglio, for instance.” Hayter returned to Paris after the war, but by then the printmaking bug had gripped a generation of upstart printers and publishers. These print devotees of the mid-20th century invited artists to try their hand at the process and in many cases ushered in a new way of working for painters, sculptors and draftsmen. “Thankfully, all the major postwar artists made prints, and that’s why I have a business,” says Ingram of Sims Reed.

Often, it has been the printers who have helped push artists beyond their regular mediums. “All the artists have been open to experimentation,” says Sidney Felsen, who, along with Tyler and Stanley Grinstein, cofounded Gemini in 1966. Over the years, artists like Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, David Hammons and Julie Mehretu have expanded their artistic practices through the print medium with the help of Felsen and his team. “They may come with definite ideas of what they want to accomplish but find the need for many different approaches until the right one is found,” says the printer.

Robert Rauschenberg’s screen-print L.A. Uncovered #10, 1998, offered by Gemini G.E.L.

“If you talk to great artists, they see printmaking as another part of their practice that often informs what they do,” says Sharon Coplan Hurowitz, a print specialist and art adviser who has worked on major print projects over the years with Johns and Ellsworth Kelly and authored the catalogue raisonné of John Baldessari’s prints. The Philadelphia Museum’s Langdale agrees: “There are many artists throughout history — Dürer, Rembrandt, Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, Terry Winters — whose printed work has a dialogue with the rest of their work. They go back and forth between the media, and one influences the other,” she says. “Their prints were not made in isolation; they were made at the same time. They have a context.” She points to Rauschenberg as an example. “He was really fascinated with photographic imagery but also painterly gestural effects, so lithography was perfect for him because he could screen-print photos and then add other stuff. You can’t do that in another medium.”

For Jackson Pollock, printing was crucial to the evolution of his abstraction. It was several years after he printed wild constellations of blobs and squiggles, using a small printing screen that he acquired during a brief stint at a silkscreen workshop, that he began splattering canvases with similar abstract imagery. For Johns, recognized as one of the most innovative, masterful print artists of all time, the medium was ideal for exploring the ideas of repetition, seriality, patterning, semiotics, order and symbolism that intrigued him. His crosshatch prints (and paintings, for that matter) are a wonderful reference to the engraving process but also a brilliant conceptual update of Abstract Expressionist brushstroke, which Johns subverted again and again.

While printing allows for a tremendous amount of experimentation with different techniques and effects, Ingram points out that it’s important for collectors to understand the amount of forethought and decisiveness that goes into making editions. “With prints, there is real intention, and you tend to get very strong images, because when artists are making prints, they are aware that they are making twenty or thirty or fifty of them. Drawing and even painting can be more incidental,” she says.

Richard Serra uses his whole body for the creation of an artwork, 1998. Photo © Sidney B. Felsen

For some, the idea that there is more than one of these works out there is a big draw. “Because it’s a multiple, it means the Whitney or the Met or MoMA might own it, and you can own it too,” says Senior. It also means that the production process often has a high level of transparency. “Because there are multiple impressions, you can track something down and there are records that can be researched,” Hurowitz notes. “That’s not the case with a painting or drawing.”

Most major museums have departments dedicated to collecting prints. The Metropolitan Museum of Art marks the 100th anniversary of its print collection this year with the meaty exhibition “The Power of Prints: The Legacy of William M. Ivins and A. Hyatt Mayor,” a celebration of the department’s visionary founding curator and his protégé (on view through May 22). And as curators are tending to take a more holistic approach to organizing shows, says Senecal, far more light is being shed on the important role prints have long played for many artists. She points to “Jackson Pollock: A Collection Survey, 1934–1954” — a current show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (through May 1) that traces the evolution of the artist’s abstraction — as an example of the progress that has been made over the past few decades. The exhibition uses Pollock’s engravings, lithographs and screen-prints, alongside his paintings and drawings, all from MoMA’s collection, to demonstrate the evolution of his abstraction and to convey his fascination with the process. “Basically,” says Senecal, “the museum is saying that if a print is worthy of being in the museum’s collection, then it’s worthy of being in any show we curate.” That attitude also reflects the way art lovers acquire works today, she adds, with prints earning pride of place in even the most outstanding collections.