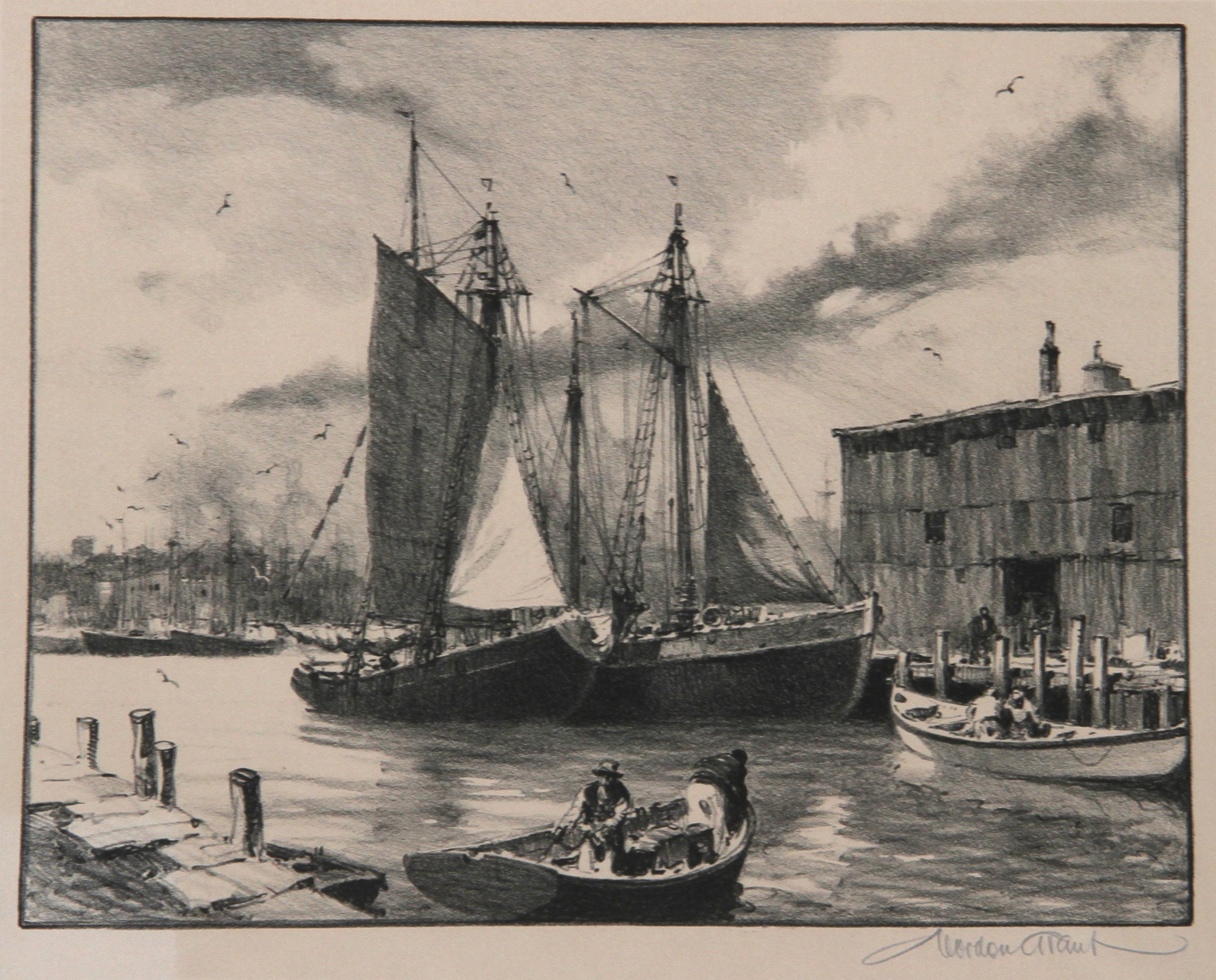

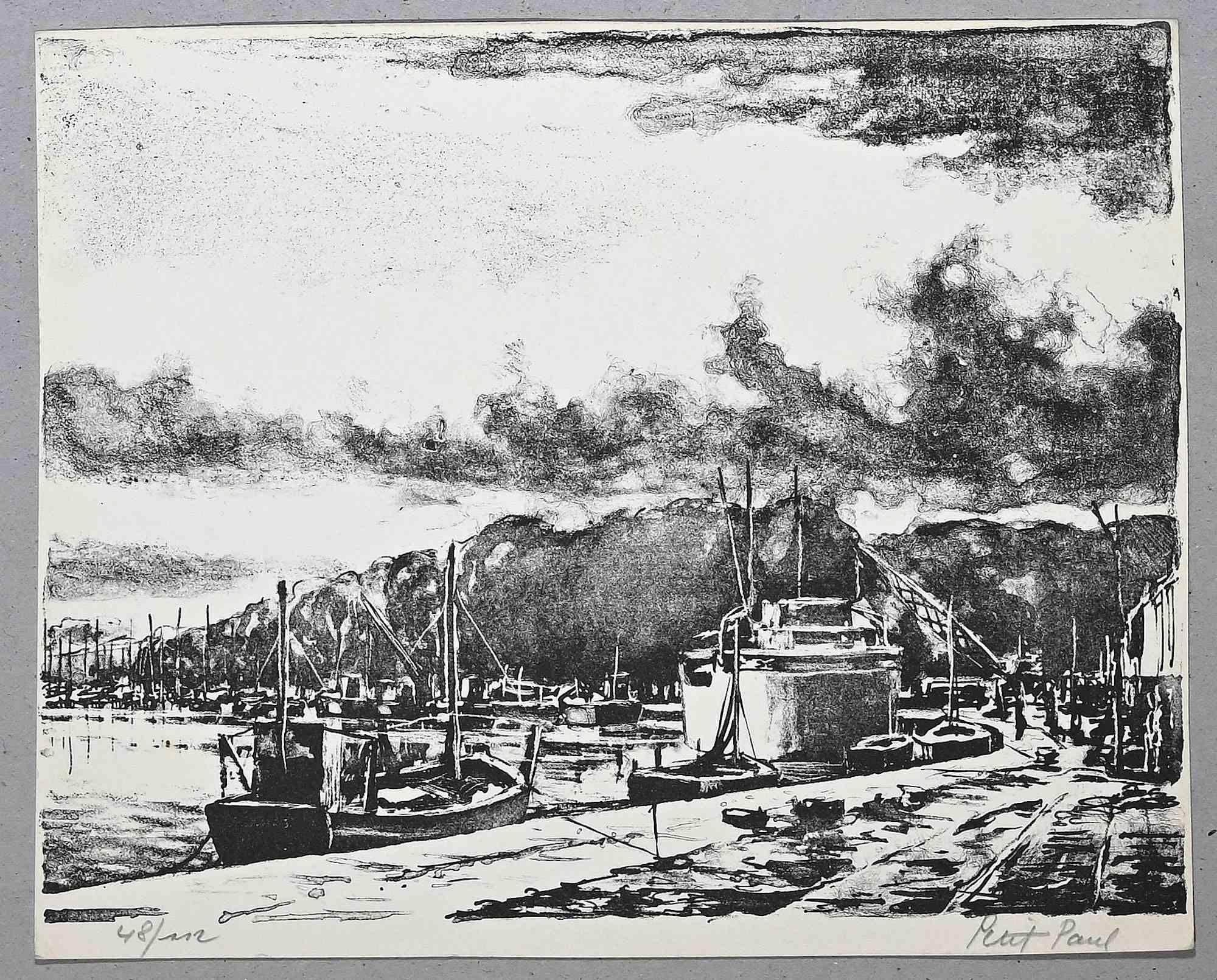

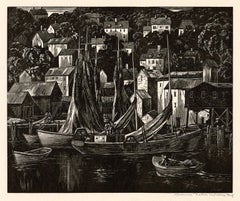

Joe Jones

Fishing Village, 1949

Signed in pencil lower right margin

Lithograph on wove paper

Image 9 5/16 x 12 9/16 inches

Sheet 12 x 15 15/16 inches

From the edition of 250

The initial details of Jones' career are sparse, and this is intentional. The young artist was engaged in a process of self-reinvention, crafting a persona. When he submitted a work to the Sixteen Cities Exhibition at New York City's Museum of Modern Art in 1933, he briefly characterized himself: "Born St. Louis, 1909, self-taught. " Jones intentionally portrayed himself to the art community as an authentic working-class figure, backed by a compelling history. He was the youngest of five children in a family led by a one-armed house painter from St. Louis, a Welsh immigrant, and his German American spouse. At the age of ten, Jones found himself in a Missouri reformatory due to authorities' concerns over his graffiti activities. After completing elementary school, he traveled by freight car to California and back, even being arrested for vagrancy in Pueblo, Colorado. Returning to St. Louis, he attempted to settle down by working alongside his father. Yet, Jones felt a profound restlessness and was drawn toward a more elevated artistic pursuit in his late teenage years. He discovered a local collective of budding artists that formed St. Louis’s "Little Bohemia," sharing a studio and providing mutual support until he managed to secure his own modest workspace in a vacant garage.

Jones’s initial creations comprised still lifes, landscapes, and poignant portraits of those close to him. These subjects were not only accessible but also budget-friendly, as hiring models was beyond his means. He depicted himself, his father, mother, and eventually, his wife. In December 1930, at the age of 21, Jones wed Freda Sies, a modern dancer and political activist who was four years older than him.

By 1933, Jones had started gaining noteworthy local recognition through a solo exhibition at the Artists’ Guild of Saint Louis. Of the twenty-five paintings on display, one, titled River Front (private collection, previously with Hirschl and Adler Galleries), was selected to illustrate a feature article about his show in The Art Digest (February 15, 1933, p. 9). Shortly before this exhibition, a young surgeon named Dr. Robert Elman took an interest in Jones’s art, purchasing several pieces and forming a group of potential patrons committed to providing the emerging artist with a monthly stipend in exchange for art. This group was officially known as the "Co-operative Art Society," but it was informally dubbed the "Joe Jones Club. " Jones became an active participant in the St. Louis artistic scene, particularly within its bohemian segments. He embraced modernism and was a founding member of the "New Hat" movement in 1931, a playful rebellion against the conservative and traditional mainstream art establishment.

The summer of 1933 marked a significant shift in Jones’s journey. Sponsored by a dedicated ally, Mrs. Elizabeth Green, Jones, along with Freda and Green, embarked on an eastward road trip. In Washington, D. C., they explored the Corcoran Gallery of Art, the Freer Gallery (part of the Smithsonian Institution), the Library of Congress, and Mount Vernon. Following this whirlwind of art and American culture, they made their way to New York, where they visited various museums and galleries, including a stop at The New School for Social Research, which featured notable contemporary murals by fellow Missourian Thomas Hart Benton and the politically active Mexican artist, José Clemente Orozco. From June through August, Jones and Freda resided in the artist colony of Provincetown, Massachusetts, later returning home via Detroit to see Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry mural housed at the Detroit Institute of Fine Arts.

While Elizabeth Green allegedly hoped that Jones would refine his artistic skills under the guidance of Charles Hawthorne or Richard Miller in Provincetown, Jones followed a different path. Rather than pursuing conservative mentors, he connected with an engaging network of leftist intellectuals, writers, and artists who dedicated their time to reading Marx and applying his theories to the American landscape. Jones's reaction to the traditional culture of New England was captured in his statement to a reporter from the St. Louis Post Dispatch: “Class consciousness . . . that’s what I got of my trip to New England. Those people [New Englanders] are like the Chinese—ancestor worshipers. They made me realize where I belong” (September 21, 1933). The stark social divisions he witnessed there prompted him to embrace his working-class identity even more fervently. Upon returning to St. Louis, he prominently identified himself as a Communist. This newfound political stance created friction with some of his local supporters. Many of his middle-class advocates withdrew their backing, likely influenced not only by Jones’s politics but also by his flamboyant and confrontational demeanor.

In December 1933, Jones initiated a complimentary art class for unemployed individuals in the Old Courthouse of St. Louis, the same location where the Dred Scott case was deliberated and where slave auctions formerly took place. Concurrently, the St. Louis Art League was offering paid courses. Emphasizing the theme of social activism, with a studio adorned with Soviet artwork, Jones’s institution operated for just over a year before being removed from the courthouse by local officials. The school’s political focus and unconventional teaching practices, along with its inclusion of a significant number of African American students during a period marked by rigid racial segregation, certainly contributed to its challenges. Under Jones’s guidance, the class created a large chalk pastel mural on board, measuring 16 by 37 feet, titled Social Unrest in St. Louis. Mural painting posed no challenge for the former housepainter, who was adept at handling large wall surfaces. His first significant commission in St. Louis in late 1931 was a mural that celebrated the city’s industrial and commercial fortitude for the local radio station, KMOX. This mural, aimed at conveying optimism amid severe economic hardship, showcased St. Louis's strengths in a modernist approach. When Jones resumed mural work in late 1933, his worldview had evolved considerably. The mural produced for the school in the courthouse, conceived by Jones, featured scenes of modern St. Louis selected to highlight political messages. Jones had observed the technique of utilizing self-contained scenes to craft visual narratives in the murals he encountered in the East. More locally, this compositional strategy was commonly employed by the renowned Missouri artist Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975). As early as October 1933, after returning from Provincetown and realizing that his Communist ties were problematic for local patrons, Jones wrote to Elizabeth Green expressing, “I sincerely believe that I am as far as I can go in St. Louis. ” By the end of 1934, in search of broader opportunities, he exhibited three oil paintings in prominent East Coast group exhibitions: American Justice, a powerful anti-lynching piece at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts (currently housed in the Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio); Road to the Beach, a landscape from Provincetown (in the Museum of Modern Art, New York); and Wheat at the Whitney Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting. These works showcased both his artistic proficiency and his aptitude for various subject matter.

Jones’s home life had reached a critical juncture. In December 1934, Freda Jones was taken into custody for "disturbing the peace" during a political rally outside St. Louis City Hall. However, their shared political beliefs failed to salvage the relationship. The couple ended their marriage and eventually divorced, prompting Jones to move back in with his parents. Clearly, a change was necessary. He returned to New York and immersed himself in museums and galleries while seeking representation in the city. By this time, his artwork had become distinctly political. Both Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery and The Rehn Gallery rejected his work. He submitted a piece to an anti-lynching exhibition at the A. C. A. Gallery, which led to a comprehensive partnership and the notable 1935 exhibition. Herman Baron recognized Jones’s talent and grasped his origins and aspirations. Reflecting on this, Baron noted that the artist "as a young boy. . . envisioned wealth in adulthood; to him, success signified acceptance into the upper echelons. ” Jones did not remain long in New York. He returned to St. Louis in April and missed the opportunity to view his exhibition at A. C. A. In August and September 1935, he documented the challenging lives of rural laborers in Arkansas for a mural at Commonwealth College in Mena, Arkansas. This socialist institution functioned as a training ground for organizers of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union. Although it closed in 1940, the mural, The Struggle in the South, measuring 9 x 44 ft., was fortuitously preserved and has recently undergone restoration. It now holds a prominent place at the University of Arkansas Little Rock Downtown campus in the River Market District.

During the later 1930s, Jones’s subject matter shifted, becoming less overtly political and more focused on workers and African Americans, primarily in rural settings. In 1936, he produced a commercial mural for a downtown taproom in St. Louis. The five-panel piece, fittingly titled The Story of the Grain, was a success and featured prominently in the 1936 emphasis on rural Midwestern-themed artworks. In January 1936, Jones participated in another New York exhibition, “Paintings of Wheat Fields,” hosted at the Walker Gallery. Although Herman Baron collaborated with this show, it represented a significant step for Jones. Maynard Walker founded his gallery in 1935, leveraging connections with Thomas Hart Benton, John Steuart Curry, and Grant Wood. Clearly, Jones aspired to be identified alongside these renowned figures. At the end of 1936, Jones submitted Our American Farms to the Whitney Museum’s Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting. The artwork depicted a dystopian view of the ecological devastation from drought and emerged from Jones’s six-week role as a Special Skills Artist in July and August 1936 with the Resettlement Agency, a New Deal program aimed at relocating farmers from dust bowl territories to regions with more viable soil. Our American Farms was one of eight pieces acquired by the Whitney Museum from the exhibition for its permanent collection.

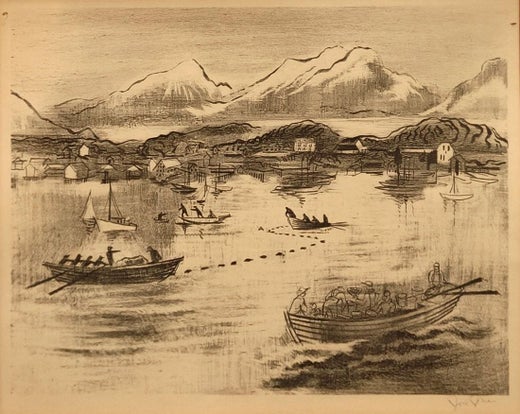

The 1940s marked a significant departure from the previous decade in terms of politics, economics, and, for Jones, his personal life. A war-driven economy took the place of a prolonged financial downturn. Following the ill-fated Hitler-Stalin agreement of 1939, Soviet Russia and the American Communist Party aligned closely with the United States during World War II. Jones had previously formed intimate connections, both professional and personal, with women from the upper strata of St. Louis society. In 1940, his affair with Grace Adams Mallinckrodt (1918–2002) made headlines in St. Louis when a private investigator found them together in Jones's cabin in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. Mallinckrodt was the young spouse of Henry E. Mallinckrodt, whose father was the president of the Mallinckrodt Chemical Company. The Mallinckrodts belonged to one of the wealthiest and most socially elite families in St. Louis. Grace Adams, introduced to societal life in Albany, New York, first met Henry Mallinckrodt during his time as a Harvard student, and they wed in 1937. Jones encountered Mrs. Mallinckrodt in 1939 when “she posed for him.” The scandalous divorce trial identified Jones as a co-respondent. This incident effectively concluded Jones’s reputation as a bold provocateur and certainly marked an end to his time in St. Louis. The couple eventually wed and relocated to Morristown, New Jersey, where they led a quiet life, parenting four children. During World War II, Jones worked as a combat artist for Life Magazine. His artwork evolved from its earlier anger and political commentary, shifting from the broad techniques linked to American Scene and Social Realism to a more refined and linear style inspired by Japanese art and Impressionism. In the years following the war, he painted coastal scenes of New Jersey and Bermuda, while also establishing a commercial career by creating advertising visuals, magazine artwork, and murals for various companies. Jones passed away from a heart attack in 1963 in the affluent and refined community of Morristown, New Jersey, where he complemented his freelance endeavors by teaching art at local private boys’ schools. This life was a far cry from his tumultuous beginnings.