July 21, 2024“It was very Grey Gardens,” says Abby Kasonik, describing the home her mother, Camille Price, bought in 1999. What had been a simple farmhouse outside Charlottesville, Virginia, it had been turned into a showplace by ambitious owners in the 1950s. The well-known preservation architect Milton Grigg added columns and a classical pediment to the original facade and added rooms to the back. But when Price bought it, nearly half a century later, the house was a wreck, with a leaky roof, crumbling plaster and wildly overgrown plantings. She threw herself into repairing and upgrading it, even installing an elevator to whisk her to her bedroom.

Like many renovators, she was bored once the job was complete. So, in 2017, she told her daughter, “Unless you want it, I’m going to sell it.” Soon, Kasonik and her partner, Rod Coles, were living in the house with their now-nine-year-old daughter, Margaux — and Price was ensconced in the cottage just across the driveway.

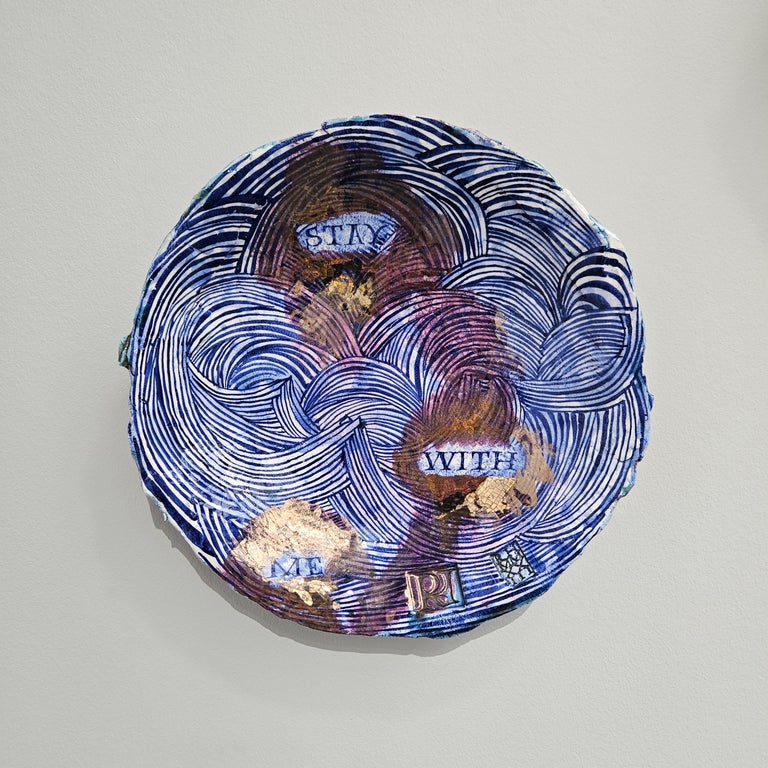

When the house was built, in the 1830s, it consisted of six 18-by-18-foot rooms, in a two-over-two-over-two arrangement. Those proportions meant every room was big enough for multiple furniture groupings. A minimalist compared with her mother, who seemed to fill every inch of every surface, Kasonik has tried to reduce the clutter. On the other hand, the two women share a penchant for eclecticism — pieces range widely across periods and styles. Most of the rooms, however, have a common element: at least one of Kasonik’s functional ceramic sculptures. Some of them, she says, “are classic shapes in wacky colors”; some are the other way around. When it comes to deciding where to place them, Kasonik has no rules. But she does have thoughts: “If a room is calm, with mostly solid colors,” she says, “You can get away with a jazzy pattern on an accessory like a lamp.” And if a room already has stripes or plaids on curtains and upholstery, that’s OK too: “I think pattern on pattern is really fun.”

A Charlottesville native, Kasonik studied art at Virginia Commonwealth University, expecting to become a sculptor. But after graduating, around the turn of the century, she switched from three to two dimensions. For the next 20 years, her specialty was creating abstract landscapes in acrylic paint. She was successful, but as the pandemic took hold, she found herself wanting to try something new. In a pottery class, she began making not the usual vases or mugs but tabletop sculptures. “I just like making things — especially with clay, which is so elemental and which you can totally transform with heat and paint,” she says. “And when I make something I think is good, then I want to put it out there.”

She began selling her work and quickly discovered that “not everyone knows what to do with a sculpture in their house.” Accordingly, she looked for ways to make the pieces functional, in some cases adding wiring and bulbs and lampshades so “you can have this cool, weird thing, but it’s a light.” (Some of the shades were made by her collaborator, Kiki Slaughter.) Other pieces have flat tops and work as occasional tables. Although they’re hollow, they’re heavy enough, she says, “that your cat can’t knock them over.”

Her studio is in a former barn on the 18-acre Charlottesville property. There, each piece is handmade by Kasonik; no two are exactly alike. A customer seeking a matched pair (say to place on bedside tables), will have to settle for — or perhaps revel in — slight variations.

In Kasonik’s own house, her works fit comfortably into the dining room’s casual scheme. “I’ve never liked the kind of formal dining room where you have to sit up straight,” says Kasonik. “We use the table for doing puzzles and playing games like Battleship.” The space’s ample dimensions meant she could squeeze in a couch or two. Over the painted-wood dining table is a vintage reed chandelier; around it are four faux-bamboo-backed Hollywood Regency chairs by Baker. Kasonik’s own pieces include a small table that looks like a salt shaker and a striped lamp, standing in the window. Both pick up on other patterns in the room. “You look for commonalities, and then you mix and match,” she says.

Her mother painted the walls of the TV room a mottled green. Two vintage sofas face a mirror-topped table on a faux zebra rug — black and white stripes printed on cowhide. An off-white free-form table by Kasonik goes well with the off-white free-form rug. The blue-and-yellow table lamp intensifies the colors of the sofa and Kasonik’s painting. A lot of her pieces, the designer says, “have a bodily quality to them — you know, hips and waists and bulges.”

The house’s kitchen is long and narrow. At one end, a resin chandelier from Oly Studio draws the eye upward. To the right of the window is a blue-and-white sculpture by Kasonik. To the left of the window is her swirly blue painting and an old carved marble lamp. Two Michael Wolk Miami chairs are endearing in shearling. At the other end of the kitchen, a pair of Italian bentwood cafe chairs sit at a Gustavian-style table. Kasonik made the pair of 20-inch-tall blue lamps on the bar.

The original kitchen was in a separate building. Now it’s Kasonik’s office, its walls painted Farrow & Ball’s Studio Green. In place of a desk, she has an old baker’s table, with a wooden frame and metal top, from Kenny Ball Antiques. The neoclassical barrel-back chair is her office seating.

The couple’s bedroom is painted in Farrow & Ball’s Great White, which is actually a very pale lilac. Old chairs were covered in a new Schumacher x Miles Redd windowpane-patterned fabric. Next to the bed, a Kasonik lamp — ceramic with a gold-leaf finish — stands on an oval occasional table. The painting above the lamp is by Coles’s mother, Jessie Coles. The painting next to the lamp is by Sarah Boyts Yoder, who shares Kasonik’s studio space.

Kasonik stood a marble Buddha and a pair of silver urns on the room’s mantelpiece. A collection of her works hangs on the wall above: small ceramic plates circling a mirror with a carved ceramic frame. The shapes of the protrusions are derived from nature, Kasonik says.

Compared with the other rooms, the center hall may be the least polished, but that’s not a bad thing. When her mother bought the house, the hall, Kasonik says, had “hideous mauve wallpaper.” Price tore it down, leaving the yellow wallpaper glue behind, for a kind of hand-plastered effect. Kasonik’s contribution: knowing not to touch it. She may soon add one of her ceramic tables to the mix of furniture. What color? What pattern? That’s to be determined. But, she says, “it really doesn’t have to be a perfect match.”