August 16, 2020Modernism has kept a tight hold on the imagination of architecture lovers, remaining for many the epitome of style long after its ostensible heyday in the middle of the 20th century. Now, three books shine a spotlight on four towering figures of the movement — starchitects, before the phrase was coined — whose lives and careers were intertwined. Their radical innovations pushed postwar architecture in a multitude of directions, something clearly visible today in their buildings that remain standing.

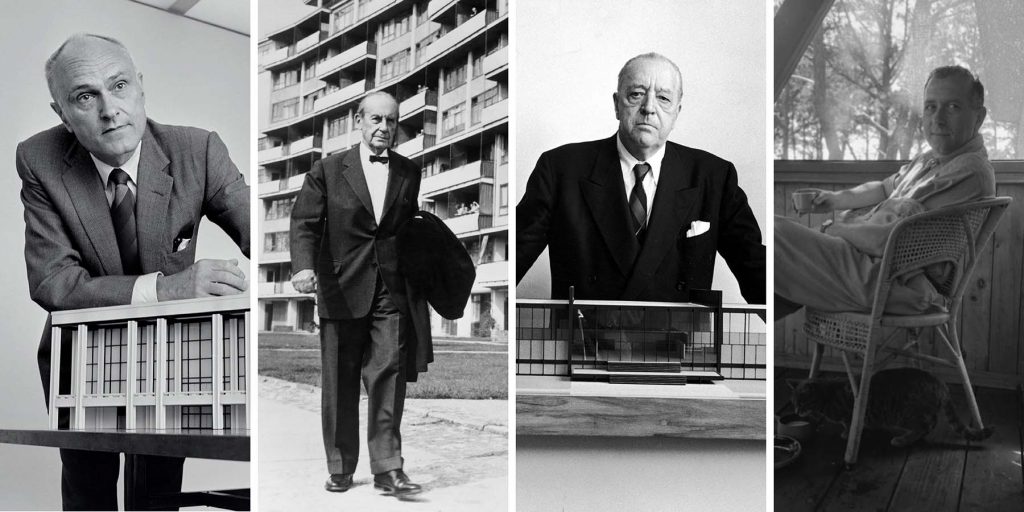

It can be dangerous to reduce architecture to the personalities of those who make it, but the taciturn German genius Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) and the adaptable American gadfly Philip Johnson (1906–2005) made an utterly fascinating odd couple — and not only for their collaboration on one of the most iconic structures of the 20th century, New York’s Seagram Building. As the first two books demonstrate, neither would have achieved what he did without the other.

“Mies Has No Taste”

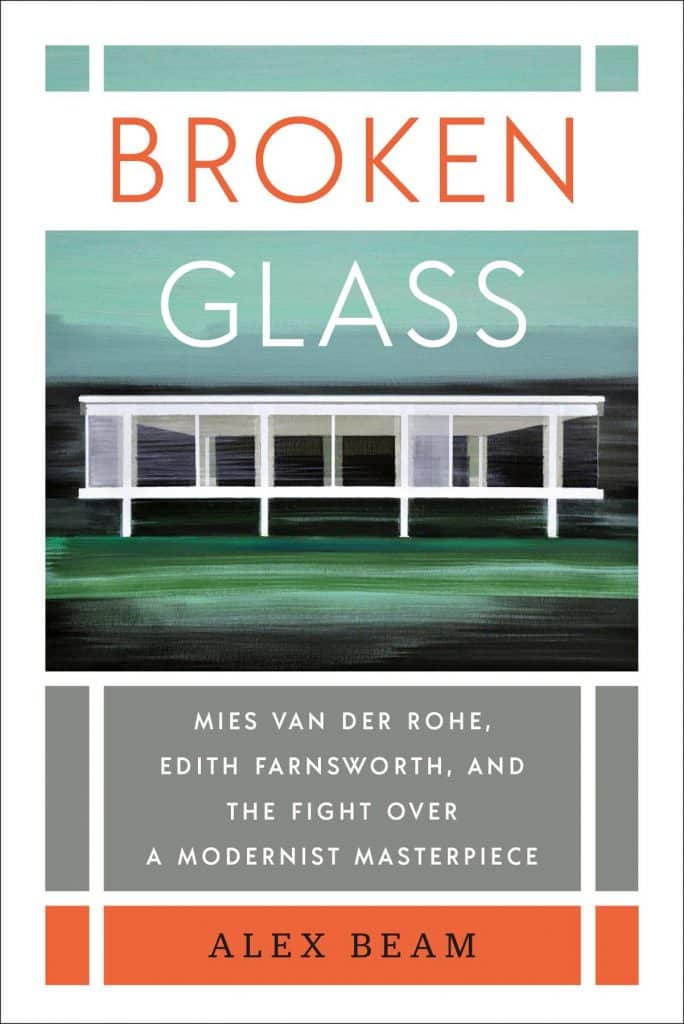

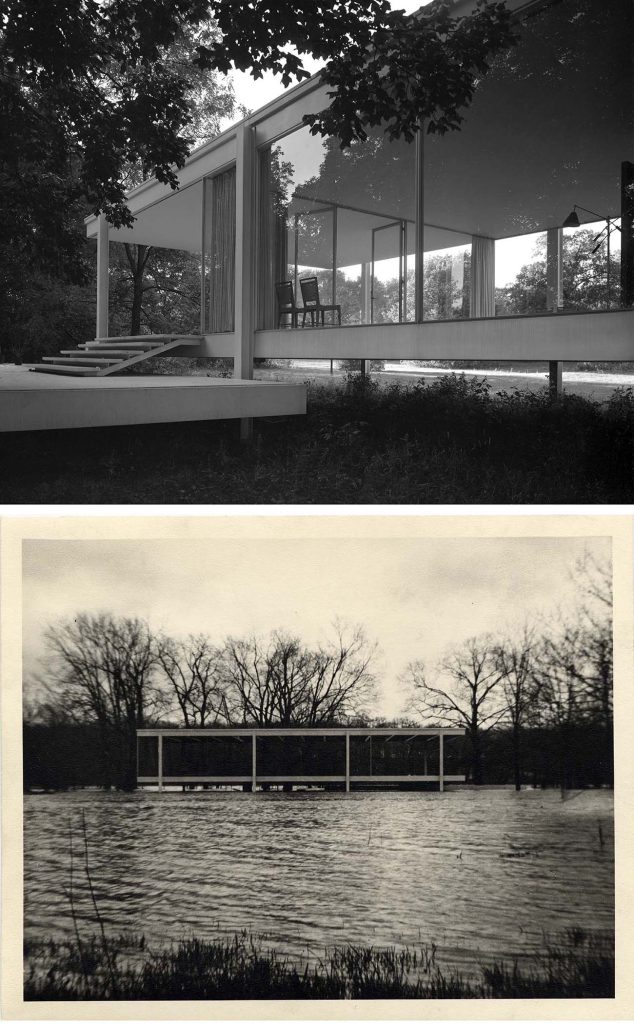

Alex Beam’s Broken Glass: Mies van der Rohe, Edith Farnsworth and the Fight over a Modernist Masterpiece (Random House) is a deep dive on one very famous and contentious project. For anyone who’s ever hired an architect to do anything, the basic premise of Broken Glass will ring true: Building things is hard, a process rife with busted budgets and miscommunications. In this instance, perhaps because the achievement of the Farnsworth House was so epic, the associated rancor was too. Elevated a few feet off the ground on white-painted steel beams so that it almost seems to float, this supremely chic glass box was set on a pastoral site that caused much more than its fair share of problems. A single story “pavilion,” with its structure expressed for all to see, it was elegantly self-contained but also superbly open to nature, thanks to floor-to-ceiling windows.

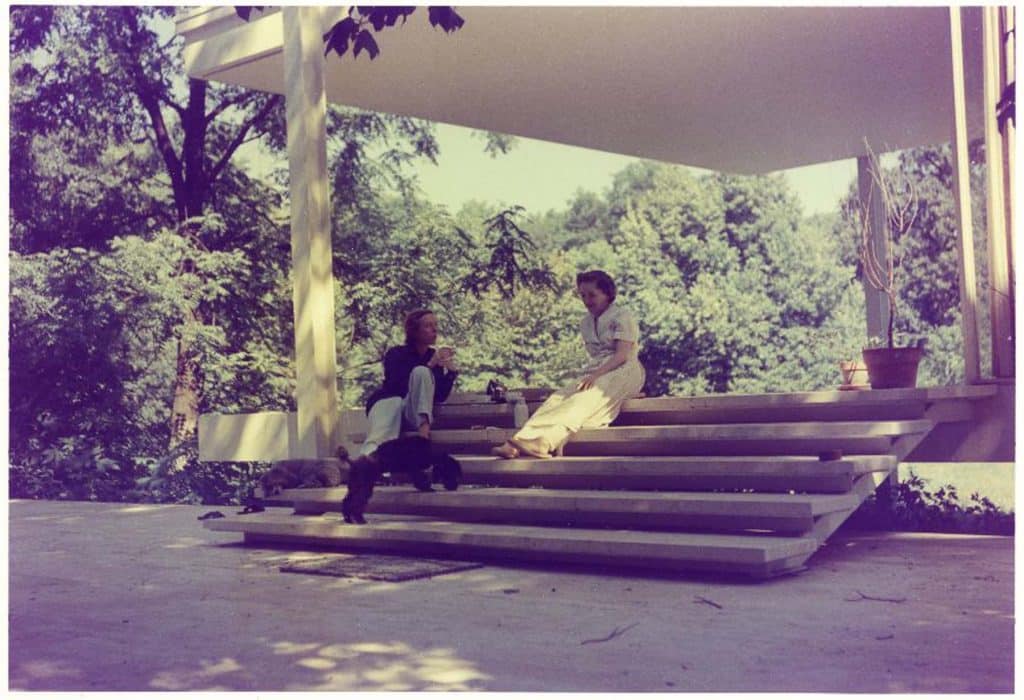

It all began in 1945, when the well-to-do and sharp-tongued Edith Farnsworth, an accomplished physician, met Mies at a Chicago dinner party. The architect, who’d immigrated to the U.S. seven years prior, was already a Bauhaus legend, known for the pared-down beauty of the German Pavilion that he and Lilly Reich designed for the 1929 Barcelona International Exhibition and the accompanying Barcelona chair. Farnsworth and Mies hit it off and embarked on a country house project on the shores of the Fox River in Plano, Illinois (possibly having an affair along the way).

Six years later and many times over budget, Mies had built a masterpiece. It was perfect, except for the fact that it was prone to flooding, difficult to heat and cool, vulnerable to plagues of insects and besieged by Mies superfans with cameras — in short, nearly impossible to live in.

This, understandably, produced tension between architect and client, which intensified with Farnsworth’s rejection of the idea of using Mies’s already iconic furniture. She chose instead to go her own way, incorporating a metal dining table by Florence Knoll, among other items, and pointedly remarking at one point that “Mies has no taste.”

By 1952, Farnsworth and Mies had sued and countersued each other. Mies may have ultimately gotten the best of the legal fight, but neither came out of the process happy or with undented reputation. Beam, the book’s author, has a talent for concisely sketching each personality, as well as the gory details of the trial.

Despite Farnsworth’s well-documented qualms, the house became the stuff of legend. She lived there until 1969, when she sold it to Lord Peter Palumbo, who auctioned it off in 2003 at Sotheby’s. It’s now run by the National Trust for Historic Preservation and open to the public.

Meet Modernism’s Greatest Showman

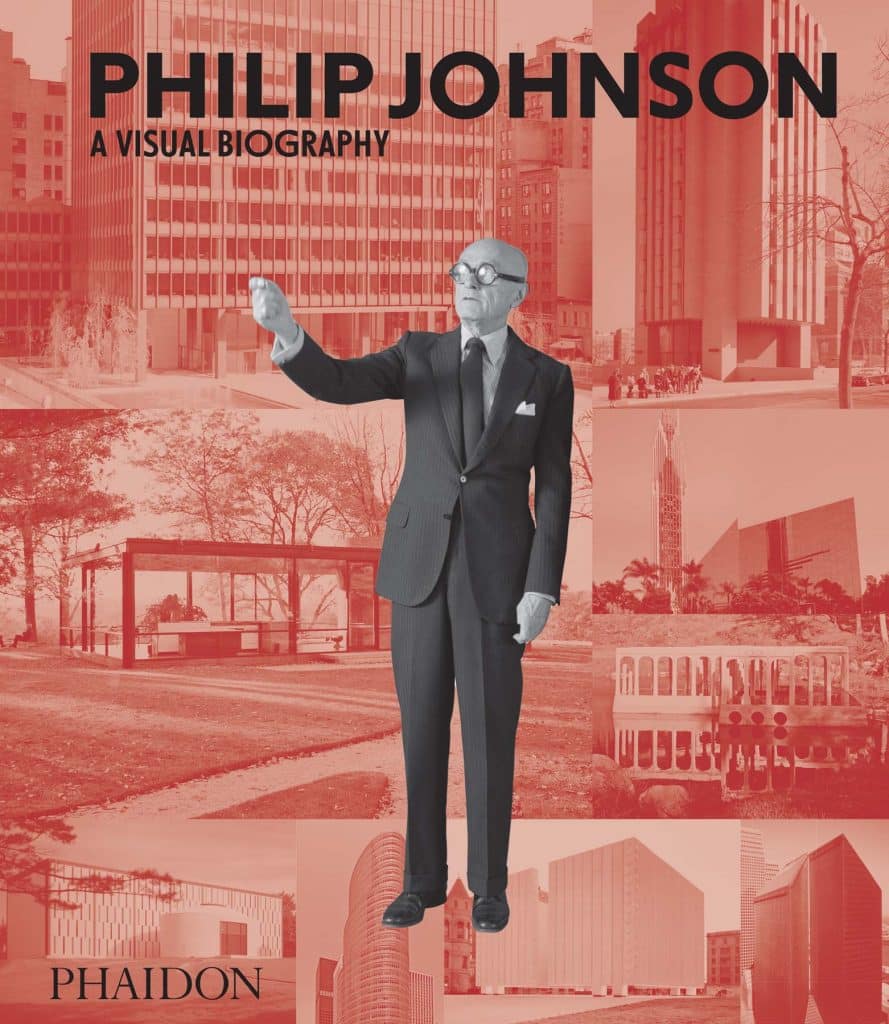

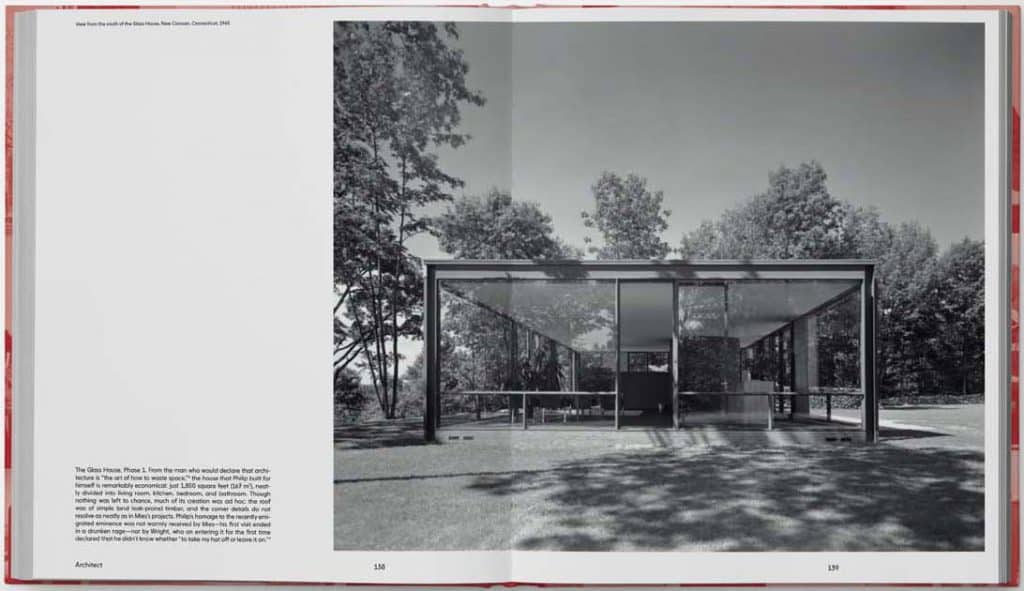

The Farnsworth House’s aesthetic successes were not lost on Johnson, who admitted to cribbing from it for what is his most famous structure: his Glass House, which he built for himself in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1949. Ian Volner’s Philip Johnson: A Visual Biography (Phaidon) is a visually driven chronicle of a whole life, and the Glass House is certainly among the high points.

As it happens, the Farnsworth House saw so many delays that the Glass House was finished first. Like Mies’s opus, it was a chic modern box. But differences abounded: It used black steel instead of white, lacked both porch and terraces — two Farnsworth signatures — and had a brick cylindrical volume for the bathroom. Further, it didn’t look as if it were floating above the ground, as Mies’s creation did. Mies thought the Glass House undeniably inferior to his own creation, and said so. But Johnson’s talent for public relations helped make his home perhaps the most renowned of the 20th century.

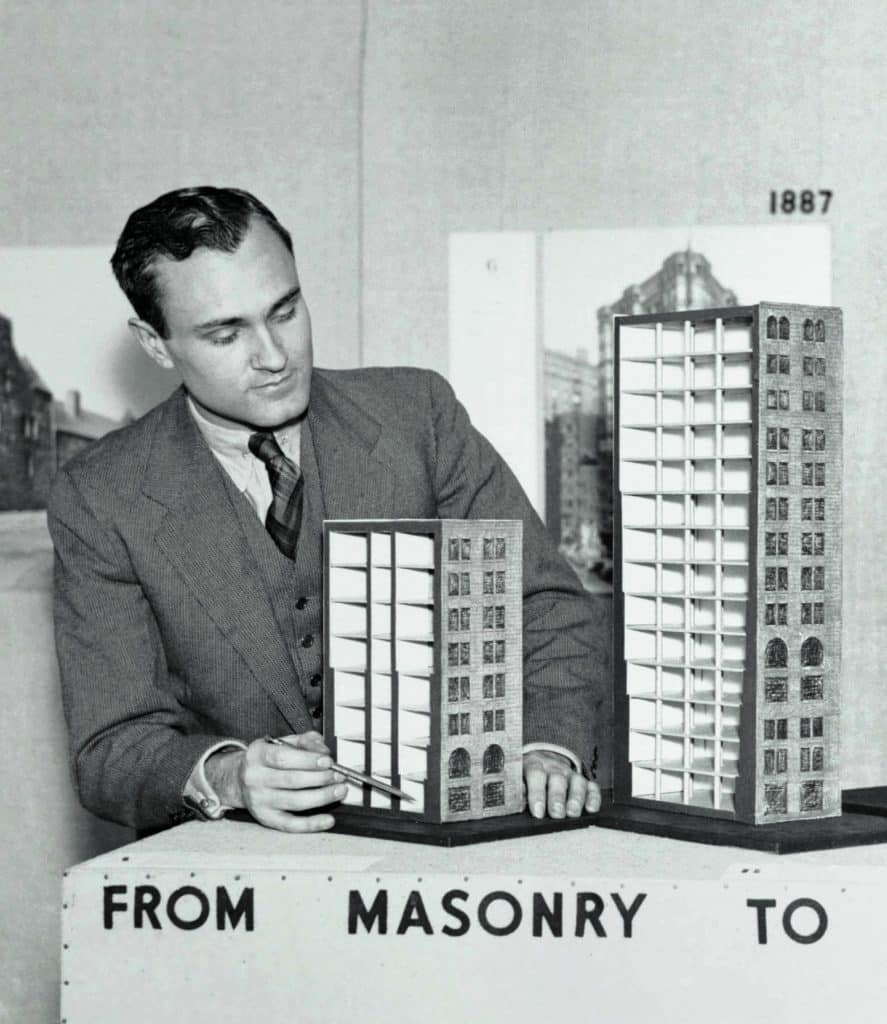

As Volner’s book demonstrates — through photos, floorplans, news images and other documents, as well as short texts interspersed among these —Johnson’s family fortune allowed him to have several intertwined careers. His work as an architecture curator at the Museum of Modern Art — from 1930 until 1936 and again from 1946 to 1954 — is in many ways his most lasting legacy. Johnson helped invent the role and, in the process, shaped the whole story of 20th-century design, not least by burnishing the legacy of Mies himself with a large 1947 retrospective.

In 1940, after a stint in journalism, Johnson returned to Harvard (where he had previously majored in philosophy as an undergraduate) to study architecture at the university’s Graduate School of Design, going back and forth between study and practice. Thus began another career in which he made a significant mark.

His contribution to the Seagram Building — the ultimate modern skyscraper, set at the back of a granite plaza, austere and chic at the same time, a tall bronze-and-glass box defined by numerous strong vertical lines in the form of mullions — may have been confined largely to the interiors of the restaurants, particularly the Four Seasons. But he was, in many ways, the packager of the entire project, acting as architect of record for Mies’s design and then helping to make it famous by holding court there.

As an architect, Johnson was a shape-shifter who, late in his career, tried on postmodernism (see the AT&T — now SONY — building at 550 Madison Avenue in New York, with its Chippendale-style pediment). In doing so, he disavowed Mies and modernism — and then moved on to a host of other styles (see the so-called Lipstick Building, an elliptical enigma on Third Avenue in Midtown Manhattan, or Da Monsta, a small but loud 1995 outbuilding on his New Canaan property that feels like a Frank Gehry–inspired deconstructivist pavilion, with a touch of Richard Serra sculpture thrown in).

Volner cites critic Paul Goldberger’s opinion that, although Johnson was hardly the most important architect of the 20th century, he became its key “architectural figure,” thanks to his promotion of design and designers. His relationship with Mies was always both worshipful and prickly; Mies famously refused to stay at the Glass House when he visited Johnson, instead staying nearby. But they were enmeshed, and both knew it.

A Hidden Treasure Brought to Light

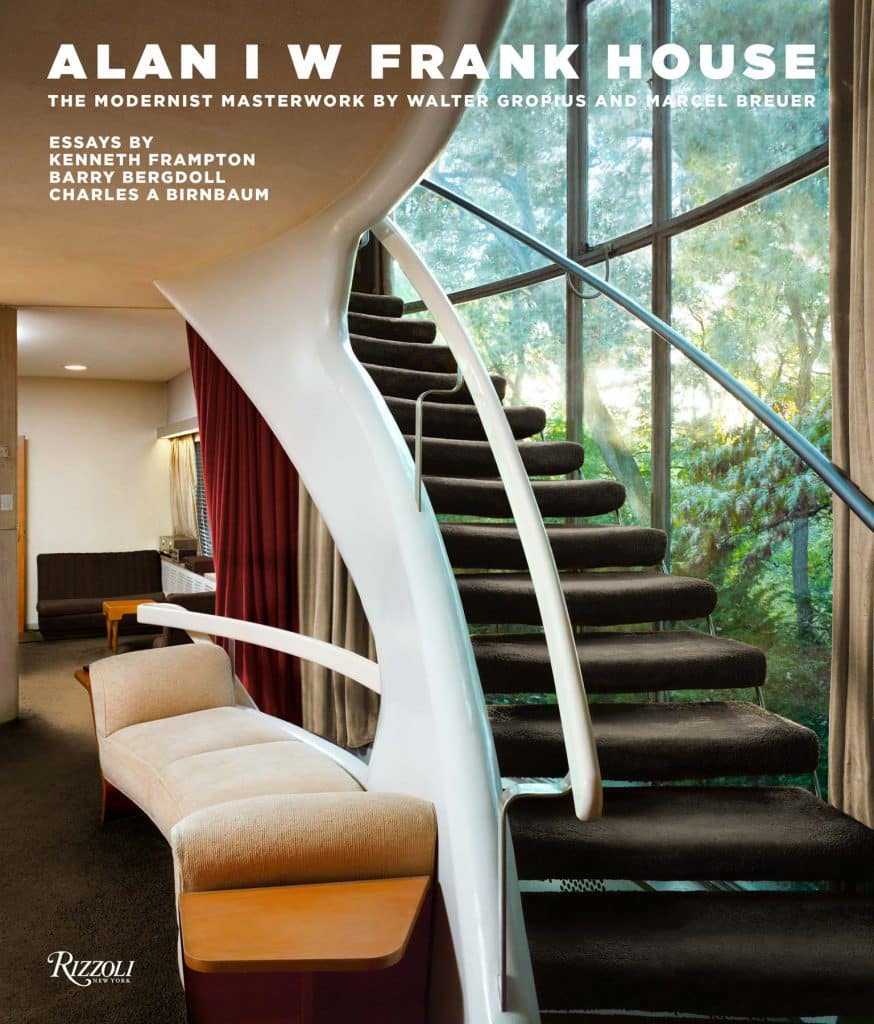

A third volume available now, Alan I W Frank House: The Modernist Masterwork by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer (Rizzoli), provides a rare view into a lesser-known Bauhaus masterpiece that’s been hiding in plain sight in Pittsburgh. Johnson is everywhere in modern architecture, if you look close enough — he’s the Where’s Waldo of the movement. So, it’s not surprising that, in the 1930s, while he was working at MoMA, he helped introduce the U.S. to the work of Walter Gropius (1883–1969), and to the Bauhaus generally. Or that at Harvard, he studied with Marcel Breuer (1902–81).

Gropius and Breuer completed the Frank House several years before the Glass and Farnworth houses were finished, but it has never before been featured in a book, so this volume’s contents count as a revelation. Essay contributors include Alan I A Frank, the son of the original owners, who is trying to preserve it; architectural historians and gurus Kenneth Frampton and Barry Bergdoll; and Charles A. Birnbaum, president and CEO of the Cultural Landscape Foundation. Photographs are the book’s focus, and the pictures of the sweeping staircases alone will thrill anyone who loves design.

Gropius, the Bauhaus’s founding director, and Mies, a later director of the school, were peers and colleagues who died within a month of each other. But the rounded forms of the Frank House’s interiors — distinctly un-Miesian — show how diverse the school’s legacy is.

As intriguing as these books are, in some ways, they serve largely to whet the appetite for visits to the buildings themselves. Architecture is best experienced in three dimensions, after all. Luckily for us, many of these designers’ structures — the Seagram Building and the Farnsworth, Glass and Frank houses, among them — not only remain intact but are open to the public. The more that’s written about great architecture, the likelier we are to keep it around.