November 16, 2025Most people with an interest in the decorative arts think they know Art Deco. It’s the Chrysler Building, Miami’s South Beach and Donald Deskey’s interiors for Radio City Music Hall. It’s Eileen Gray’s 1927 Transat armchair, Jean Dunand’s lacquer vases and the exquisitely restrained sitting room created by Jean-Michel Frank for Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles’s townhouse on Paris’s Place des États-Unis, which Yves Saint Laurent famously called “the eighth wonder of the world.”

And yet, for all its icons, the Deco aesthetic is not easy to pin down. True, the origins of the movement have long been tied to a sole Parisian design show: the now-legendary 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts. And Deco’s streamlined reinvention of classicism — marked by geometric forms, stylized patterns and a pared-down approach — dominated global design between the World Wars.

But there turns out not to be a single Art Deco look. “It’s extremely complicated to give a clear, very strict definition of Art Deco,” says Mathurin Jonchères, assistant curator of Paris’s Musée des Arts Décoratifs, where the exhibition “1925–2025. One Hundred Years of Art Deco” is currently on view. “There was no manifesto published nor any theoreticians who stated what it would be. The movement is full of contradictions.”

Indeed, the first monograph in English about the movement wasn’t published until 1968, shortly after the term “Art Deco,” derived from the name of the 1925 exhibition, started being applied to it.

An important landmark in Deco’s rediscovery came a few years after that, in 1972, with the Paris sale of furnishings from art collector Jacques Doucet’s mansion outside the French capital. Bidders included names like Andy Warhol and decorator Jacques Grange.

Since then, the style’s popularity has remained constant. The world auction record for a piece of 20th-century furniture is still held by Gray’s Dragons armchair, which brought €21.9 million ($28 million) at the Paris sale of the holdings of Saint Laurent and his partner, Pierre Bergé, in February 2009.

According to Philadelphia antiques dealer Gary Calderwood, whose Calderwood Gallery specializes in Art Deco, the movement’s influence today can be seen in the “ghost of the linear and geometric designs that are imitated in mass-produced furniture.” (The trend for minimalistic interiors that was kickstarted by designers like John Pawson and Christian Liaigre in the 1990s had its roots, in fact, in the work of Jean-Michel Frank and the aesthetic of the 1930s.)

Boston-based 1stDibs 50 designer Nina Farmer is drawn to Deco, she says, “for the way it bridges classicism and modernity.”

“There’s a confidence to its lines and materials, bold yet refined, and a sense of optimism that feels surprisingly current even today,” she explains. “I love the geometry, the craftsmanship and the mix of elegance with playfulness.” These qualities are evidenced in a Cambridge, Massachusetts, primary home and Manhattan pied-à-terre she designed for a passionate Deco collector, although she largely prefers to reference the movement, rather than slavishly replicate the style.

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs show, which celebrates the centenary of the original exhibition, illustrates not only Deco’s enduring appeal but also the wonderful contradictions noted by curator Jonchères. At the same time, it reveals connections among the style’s practitioners. Although they produced quite different creations, they shared “an ability to reduce ornamentation, to distill forms,” Jonchères says. “There’s something simplified, compared with what was being done twenty years earlier.”

Among the highlights of the current show are a Sonia Delaunay jacket with an abstract pattern largely consisting of rectangles, chevrons and triangles; a wonderfully minimalist glass and silver vase manufactured by Daum; Dunand’s Le Cirque screen, decorated with childlike figures and animals; an ultrachic chaise longue by Paul Follot; and a strikingly modern-looking armchair designed by Frank in 1928. It also shows off glittering Cartier jewelry and some 20 pieces of furniture from Doucet’s collection — presenting a unique opportunity to see many of the works from his holdings reunited for the first time since the 1972 auction.

Of particular note are the items on view that were in the original exposition. These include part of the ceremonial gate René Lalique created for his pavilion there; Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann’s Elysée credenza, its ivory-encrusted Amboyna burl facade adorned with a motif resembling a web of bubbles; and an André Groult chiffonier clad in shagreen

Comprising roughly 150 individual pavilions and stretched over 57 acres — from the Place de la Concorde across the Seine to Les Invalides — the 1925 exhibition must have been quite spectacular. Twenty-one nations participated in the show, 18 of them European, plus Turkey, China and Japan. (The United States sent a delegation.) Victor Horta designed Belgian’s pavilion and Josef Hoffmann Austria’s; Italy’s featured ceramics and porcelain by Gio Ponti.

Among the most striking structures were Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s Pavillon de l’Esprit Nouveau, decorated with paintings by such artists as Fernand Léger and Pablo Picasso; and Konstantin Melnikov’s audacious USSR pavilion, which featured angular forms, a red facade and huge expanses of glass. Situated right next to the Grand Palais, which was built for the 1900 Paris Exhibition, Robert Mallet-Stevens’s spare, block-like Tourism Pavilion incorporated a 100-foot-high concrete tower.

Emmanuel Bréon — a Deco specialist and author who founded the Museum of the 1930s outside Paris — believes the contrast between the two structures must have been arresting. “It’s incredible that in the space of twenty-five years, you could go from an eclectic palace with lots of sculptures to such a purist building,” he says.

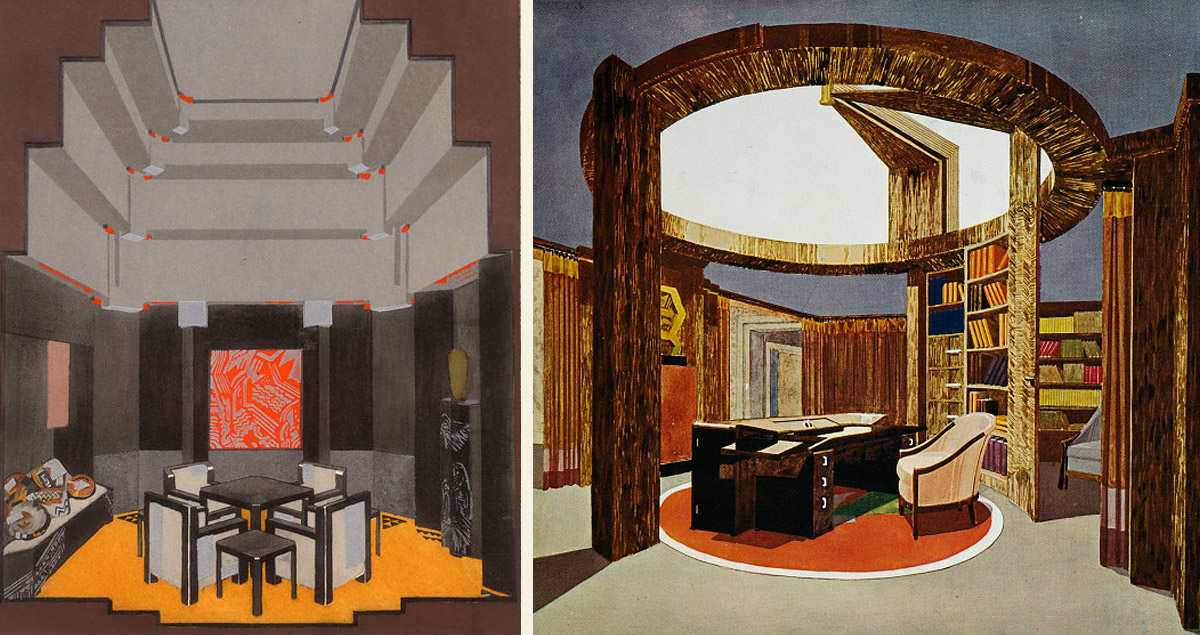

Calderwood has always been most inspired by images of the fair’s French Embassy, which consisted of numerous rooms each decorated by a different designer. Mallet-Stevens created the entry hall, Dunand a lacquered smoking room, René Gabriel a young girl’s bedroom and Pierre Chareau, in collaboration with Eugène Printz, a study-library, a reconstruction of which is in the current Paris show. “What I would give to be able to walk through those spaces,” says Calderwood. “To be able to admire the colors, the textures, the fresh design approaches and sense of harmony.”

Benoist Drut, director of New York’s Maison Gerard gallery, cites Ruhlmann’s Hôtel du Collectionneur, in which the designer brought together his own creations with those of his peers, including Émile Antoine Bourdelle sculptures, Edgar Brandt ironwork and Émile Decœur ceramics. “It was a setting of ultimate luxury, sophistication and refinement,” says Drut. Such was its success that Ruhlmann had to open a cabinetry workshop to fulfill orders.

Many people believe the 1925 exposition, which welcomed some 15 million visitors during its six-month run, launched Art Deco. But, as the Musée des Arts Décoratif’s exhibition makes clear, it actually marked the style’s high point.

The event had orginally been planned for 1912 but was postponed several times because of both World War I and financial constraints. Bréon points out that Ruhlmann had created several of the furniture designs shown in the Hôtel du Collectionneur five or six years earlier. And Calderwood notes that the genesis of the style can actually be traced back to around 1910, when designers started “carrying forward French modern design from the earlier Art Nouveau period.”

The French government organized the 1925 exhibition to ensure that the country retained its position at the center of the design world — a status threatened by decorative-art movements in other countries, such as Germany’s Deutsche Werkbund and Austria’s Viennese Secession. It certainly seems to have succeeded in reestablishing Gallic primacy, given that the vast majority of the great designers of the 1920s and ’30s were French.

The current show at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs gives three of them — Gray, Frank and Ruhlmann — their own rooms. Only Ruhlmann participated in the 1925 exposition, but the style remained prevalent right up until World War II, promoted in part by modes of transport, including the almost impossibly luxurious ocean liners like the Normandie and in Orient Express train cars decorated by Lalique and René Prou.

That iconic locomotive line is still in service, and its latest incarnation gets its own section in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs show. Contemporary French architect Maxime d’Angeac has designed the interiors for a number of antique train cars from the 1920s and ’30s recently discovered near the Polish-Belarusian border. The exhibition displays mock-ups of his schemes for the restored carriages, which Orient Express hopes to return to service in 2027.

“Art Deco endures because it balances romance and restraint,” says Nina Farmer. “Its proportions, materials and sense of scale feel timeless, while its inventive spirit continues to resonate.”

Proof of that was provided at this month’s Salon Art + Design, where Maison Gerard displayed a series of eye-catching creations by lesser-known Deco names. These included a Cactus chandelier by Albert Cheuret, first shown at the 1925 exhibition, and a pair of sconces by wrought-iron worker Marcel Bergue.

“Art Deco is all the more relevant today,” says Maison Gerard’s Drut. “It’s a style that has affected every aspect of life in such a coherent and harmonious way.”