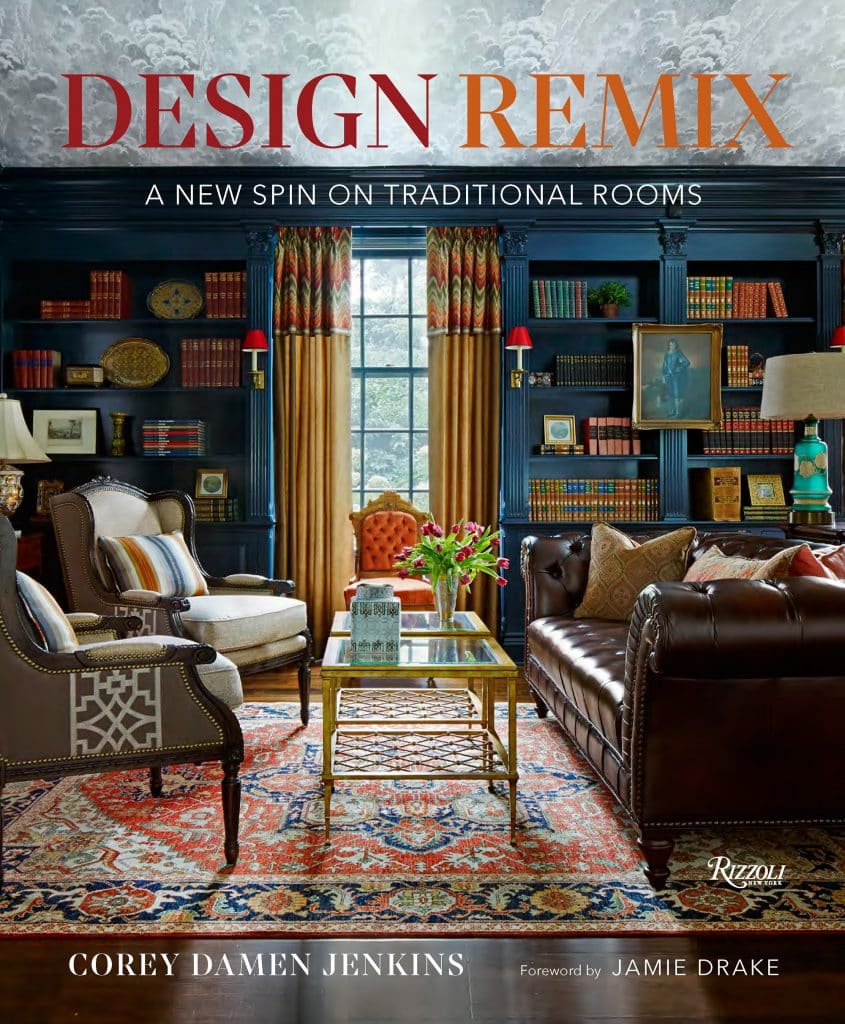

April 4, 2021Not long ago, Michigan-born interior designer Corey Damen Jenkins got a call from his editor at Rizzoli. His first book, Design Remix: A New Spin on Traditional Rooms, was due out March 23.

“Are you sitting down?” asked the editor. “You should sit down.” Preorders had proved so strong that the anticipated sellout convinced Rizzoli to schedule the book’s first reprint, even though the release date was still several weeks away.

“My heart skipped a beat. I was incredibly humbled and grateful,” says Jenkins. “I’ve always believed that the universe sends you little nudges here and there that serve as subtle reassurances. That call was just such a moment for me.”

The book’s early success served as validation for a designer who’s always succeeded by doing things his own way.

It is also evidence that Jenkins is auspiciously aligned with the current design zeitgeist. After decades of dominance by mid-century modernism and the idiosyncratic mixing of periods for personal expression, traditional decorating — and its associated color palettes and tropes — are back.

Jenkins’s version of classicism — which designer Jamie Drake in the book’s foreword calls “deliciously piquant, always with a daring touch of boldness (or quite a few)” — has landed him on the covers of various design magazines, led to appearances on HGTV and attracted a clientele of mostly young couples craving a sense of tradition. Next month, he will be honored with the Larry Kravet Design Leadership Award from the New York School of Interior Design.

Those who’ve been listening carefully will have heard the classical bell quietly begin tolling over the past five years or so. Currently, everyone from Architectural Digest to blogs like Modsy and the Glam Pad has been extolling the new traditionalism, touting toile and ballyhooing blue-and-white Chinese export porcelain. And 1stDibs’ own annual designer survey for 2021 revealed that jewel tones are the most popular colors a second year in a row, with emerald green leading the pack.

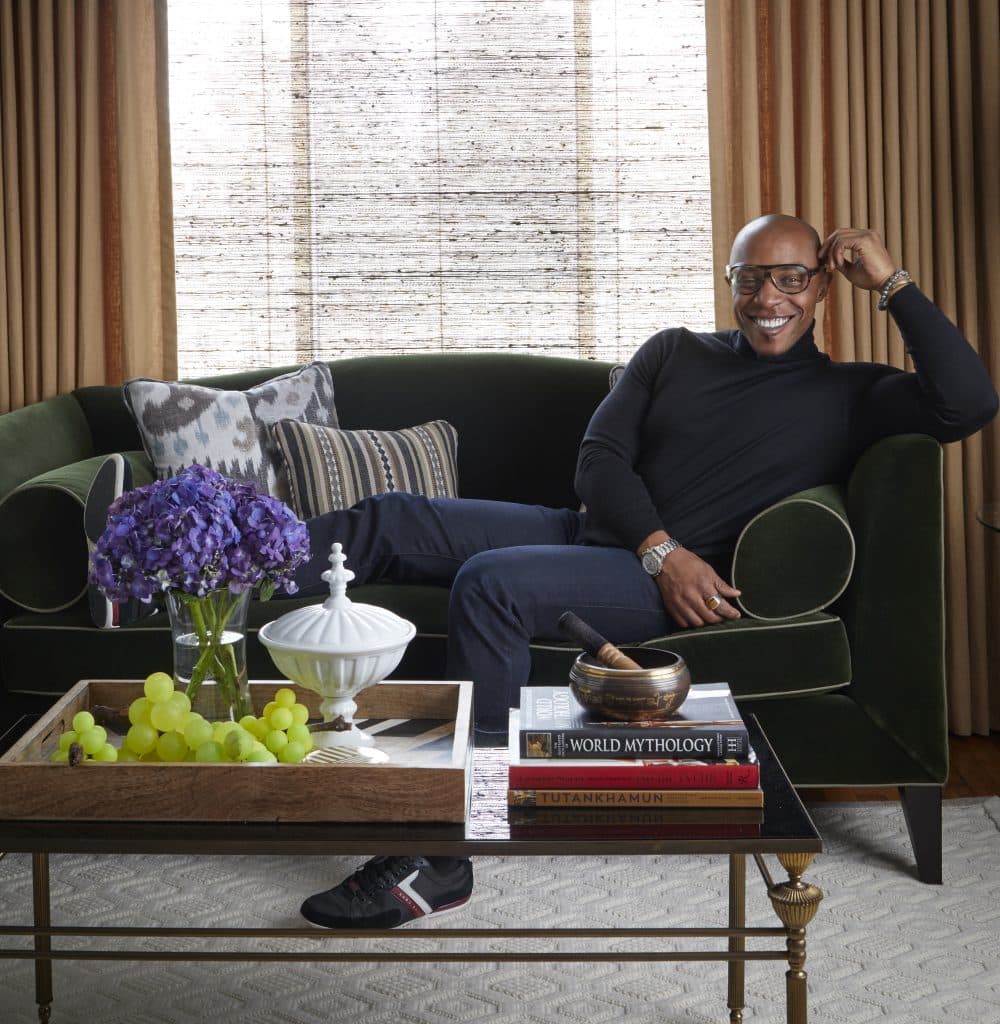

A quick flip through the pages of Jenkins’s book reveals an abundance of that color — on French-inspired sofas and bergères, on the walls of a living room and a stairwell, in a dining room’s scenic wallpaper. Ditto for 1stDibs’ runner-up hue, cobalt blue.

“I find jewel tones classic,” says Jenkins. “The Egyptians used lapis, gold and navy. I personally like to use purple, crimson, emerald green, ruby — even aquamarine. Historically, they reign supreme. They’ve always been the colors of royalty.”

Jenkins respects classic architecture, too. “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” he insists. “I might lacquer it to make it feel more modern. But Michigan and New England, where I’ve found my niche for now, are traditional regions and speak to a certain vernacular architecture. Unless a client wants something else, I’m going to build on that. Most, though, want the modern remix of traditional — the color, the wallpaper, the pattern mixing.”

Jenkins’s youthful, confidently updated approach to traditional interiors is boldly evident in his own Detroit apartment. There’s nary a white wall in the place. Instead, the predominant color is a paler lacquered version of Tiffany blue. “Since Michigan is a state doused in gray skies and winter weather,” he says, “a lot of my clients here need more color.” Jenkins apparently follows his own prescriptions.

The layering of patterns in the living room is also quintessential Jenkins: a kilim motif on an oversize wing chair, a design of golden-yellow mountains against blue clouds swathing two 1920s armchairs found at Judy Frankel Antiques and, on the green custom sofa, toss pillows dressed in ikats and stripes. “It’s about balancing scale,” he says. “You don’t want it all to be the same. If it’s all large, it’s a car crash. If it’s all small, it’s too pixelated and boring.”

Also here is a collection of — what else? — blue-and-white export porcelain. Other Jenkins signatures are peplum curtains, a detail he appropriated from fashion. “There are always a lot of peplum gowns on the runways,” he says. “Elie Saab, Jean Paul Gaultier and Valentino all love them. They go back to Jackie Kennedy. It takes drapery from being just a panel to the next level. They’re like the bodice of the gown, and the belt is the trim.”

Among Jenkins’s preferred finishing touches are papering or painting the backs of bookcases for contrast, adding couture detailing like beaded fringe and passementerie and hanging lavish chandeliers.

All of these were in evidence in his ladies’ library for the 2019 Kips Bay Show House in New York. The space included an ornately rococo desk with gilded details, a blush-pink palette, built-in bookcases papered in grass cloth and an extravagant lotus-shaped crystal chandelier from Newel.

The “deliciously piquant” touch here? Papering the ceiling (another of the designer’s signatures) with an ominously primeval-looking Cole & Son floral wallpaper. “When I suggested using this dark, almost spooky wallpaper, the girls in my office gasped and clutched their pearls,” Jenkins says. “But I reassured them it was going to be fantastic.”

Taken all together, these hallmarks prompt Jenkins to classify himself as a “new maximalist.” Yet unlike the beautiful but cluttered maximalism of such late, great designers as Renzo Mongiardino and Alberto Pinto, Jenkins’s version allows for plenty of space around the furniture he selects.

The designer’s origin story is a riches-to-rags-to-riches one. His father was a banker, his mother a homemaker. Born in Royal Oak, a northern suburb of Detroit, he grew up surrounded by “French Provincial furniture, with some rococo and a mauve-hunter-green-peach-and cream story.” His mother subscribed to Redbook, Better Homes & Gardens and Traditional Home, which Jenkins pored over under the covers with a flashlight.

Jenkins was obsessed with the way things are built. At the age of three, he was under the family’s wrought-iron dining chairs, sucking the thumb of one hand while unscrewing their seats with the other hand — much to the chagrin of guests, who kept falling through them. He enthused over blueprints of his family’s church, and when he was six or seven and his parents remodeled the house — “Well, I had opinions,” Jenkins says.

“I find jewel tones classic,” says Jenkins. “The Egyptians used lapis, gold and navy. I personally like to use purple, crimson, emerald green, ruby — even aquamarine. Historically, they reign supreme. They’ve always been the colors of royalty.”

Jenkins’s mother recognized her son’s interest. From a very young age, he was always drawing designs — for furniture, rooms, couture details, architecture — many of which she framed and displayed throughout their home. Drawing, in fact, was something Jenkins never stopped doing. And after pursuing some formal design training post-high-school, he interned for a New York–based construction-design company that was “dedicated,” he says, “to restoring historic hotels and facilities.”

The budding designer’s father was less inclined to support this career path and convinced his son to find a profession that would provide him with more financial security.

“My dad was facing a different path as an African American executive,” Jenkins recalls. “He didn’t see any Black people, especially Black men, doing design.”

So, Jenkins got a job one could consider tangentially related to design: He became a buyer for an auto company, purchasing office furniture and other supplies, working with contractors on office remodels and so on.

During the Great Recession, he was laid off. “I took it as an opportunity to rethink my direction,” Jenkins relates, “and started working in a Michigan Design Center showroom as a memo librarian, which was my first step in reentering the world of design.” But that, too, ended.

Unemployed and depressed, he says, “I traded in my luxury sedan for a 1995 Honda Accord with orange accoutrement — meaning rust — and went from shopping at Whole Foods to Spam casseroles. I decided, I’ve done it everyone else’s way, so I will bust a hole through the damn wall and make an entrance.”

His strategy? Jenkins went knocking on doors in wealthy neighborhoods with a clutch of his drawings of interiors and architecture, as well as office projects he’d worked on at the auto company. He asked any people who answered for a chance to redesign their home. The couple at the 779th home invited him in for tea and hired him.

He posted pictures of the redesign on his website in 2011. HGTV, which had been looking to diversify its design programming, came across them and called. In no time, Jenkins was cast in season one of the network’s “Showhouse Showdown” and went on to win the competition. Commissions began pouring in.

Today, Jenkins has offices in New York as well as Detroit, and apartments in both cities (the New York one awash in jewel tones, particularly sapphire), shuttling between them with his little Yorkshire terrier, Bella. There’s also a place in Puerto Vallarta that he hasn’t visited since the pandemic began. His meteoric rise has by no means made him forget his past struggles. “I learned a lesson,” he says. “I decided that if I climbed the ladder of success, I would never pull it up after me.”