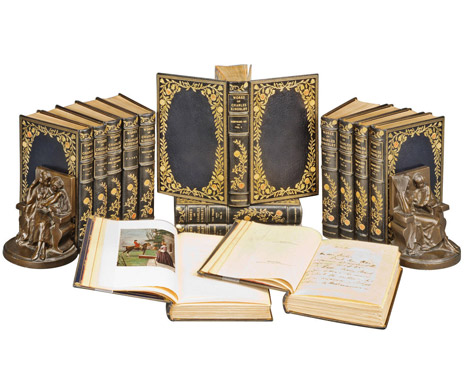

July 6, 2015The art of decorating with books reached an early zenith in Derbyshire, England, at the Duke of Devonshire’s 17th-century Chatsworth House. Centuries later, it remains carefully maintained and filled with volumes of all variety, many amassed by the 11th Duke of Devonshire, Andrew Cavendish. Top: Art 6, 2013, by Max-Steven Grossman, offered by Baker Sponder Gallery

Remember books, those charming artifacts of the second millennium? Surely one of the Western world’s greatest inventions, printed books have been around for centuries, containing nearly all of human knowledge and bringing pleasure to untold billions.

Lately, their supremacy is being challenged. As our reading options expand to include Kindles, Nooks, iPads, smart phones and more, the spaces that once contained old-school printed volumes are likely to evolve as well, whether the home library, study or living room reading nook. Libraries in grand English country houses like Chatsworth, in Derbyshire — built for the first Duke of Devonshire in the late 17th century and lovingly maintained by Andrew Cavendish, the 11th Duke of Devonshire, who kept it stocked with a stellar collection of modern political, biographical, historical and literary writings until his death in 2004 — may go on, but will the average 21st-century citizen still feel the need to live among shelves groaning with books? It remains to be seen, but if current trends are any indication, perhaps not.

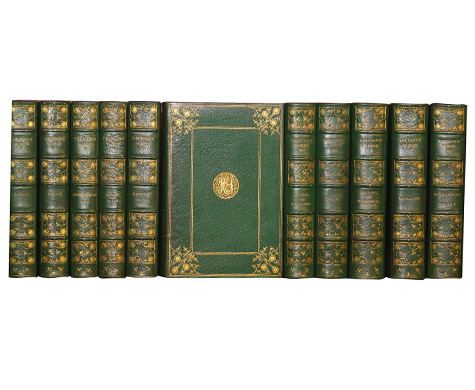

Certainly the compulsion to collect the “Great Books,” often presented in leather-bound sets, has faded. In the U.S., that late 19th- and early-20th-century fashion was inspired by the beautiful libraries of what architectural historians call the American Renaissance (circa 1876 to 1917), says architect Peter Pennoyer, an adjunct professor of architectural history at NYU, whose firm’s much-lauded projects are known for their erudite classicism.

Manhattan’s Charles McKim-designed Italian Renaissance-style Morgan Library (1906) — whose East Room features 30-foot-high triple-tiered shelves inlaid with Circassian walnut, a 16th-century tapestry and decorative ceiling depicting Socrates, Galileo, Botticelli and Michelangelo, among others — holds volumes of European literature from the 16th through 20th centuries, not least of all medieval and Renaissance illuminated texts. Photo by Graham Haber

Pennoyer calls Manhattan’s Morgan Library, an Italian Renaissance–style palazzo designed for the financier by Charles McKim and completed in 1906, “the greatest library of its kind in America, both as an incredible collection of all the great books of the Western canon and a celebration of the art of bookmaking itself — and it’s still intact.” That library, and others of its ilk, Pennoyer says, “started a tradition of Americans wanting to live with the Great Books, from Plato onward. They were considered part of the furniture. Like having a piano and sheet music, you’d have literature and philosophy on your shelf. There were lists of the Great Books, and they were considered the foundation of any home library.” He adds, “Maybe people didn’t read them, but they certainly made a more beautiful room!”

Books are still exceedingly important to many, even if they’re displayed in somewhat smaller numbers. Noted interior designer Thomas Jayne, a Winterthur-trained scholar of American decorative arts, has created many traditional paneled libraries in New England, the Hamptons and elsewhere. He says that even though his clients “have fewer books nowadays, most educated people find they need some books for aesthetic pleasure or because they like reading print.”

People still avidly seek early design and photography books, says Jayne, but they’re no longer hoarding general-interest books or novels. He finds, nonetheless, that his clients still want a serene, book-lined space somewhere in their homes as a counterpoint to the hubbub in other areas. “People like the quiet, enveloping atmosphere of a library,” Jayne says. “The density connotes coziness and comfort, and the rhythm of the paneling and bookcases makes interesting architecture.”

The principals behind Workstead, a Brooklyn-based design studio, are clearly on the same page (so to speak) as Jayne. They devoted part of the lobby at the hip Wythe Hotel in Williamsburg, which opened in 2012, to a library that achieves a striking visual rhythm, using glass-fronted barrister bookcases stacked nearly 12 feet high. “They’re modular, so there are portions where you can pull up a stool or pull out a little shelf, which makes them interactive,” says Workstead’s Stefanie Brechbuehler. Elsewhere, in the Boerum Hill brownstone of a well-known author and book collector, Workstead created a room of pale beechwood bookcases with artfully hand-crafted details, including a tier along the bottom with an angled shelf for displaying the writer’s favorite covers or spreads from art and coffee-table books. “His collection is honest,” says Brechbuehler. “It’s not books by the foot.”

Open bookshelves call for careful curating, Brechbuehler cautions. Her husband, Robert Highsmith, also a Workstead principal, rearranges their bookshelves at home just for fun, stacking some horizontally and adding an object here or there. “He finds it relaxing,” she says. Her primary tip for curating bookshelves: “Never, ever cover all your books in white paper. Let them be what they are.” Highsmith, meanwhile, likes to remove the shiny dust jackets from books and display the fabric covers. “They immediately appear deeper, richer and more muted,” Brechbuehler says.

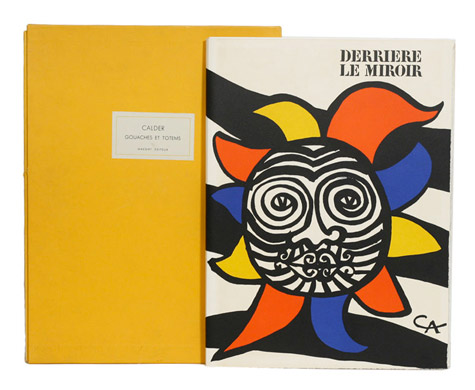

Shop Rare Books on 1stdibs

Dealers of rare and antiquarian books are seeing subtle changes in the market that reflect the modern citizen’s relationship to books. Bibi Mohammed of Imperial Fine Books, a 1stdibs dealer who also has a longstanding Madison Avenue store, specializes in 18th- and 19th-century leather-bound sets and volumes. “It’s not as busy as it used to be years ago when we would supply three or four libraries a year for a single designer in Palm Beach,” she says. “Furniture and modern art are ahead of antique books on the lists.” Her customers fall into two camps, she says. “Some people buy books as decorative objects. They want white or tan or blue books to match their rooms. Others care about the contents; they’ll ask for a set of Dickens, Jane Austen or Mark Twain.”

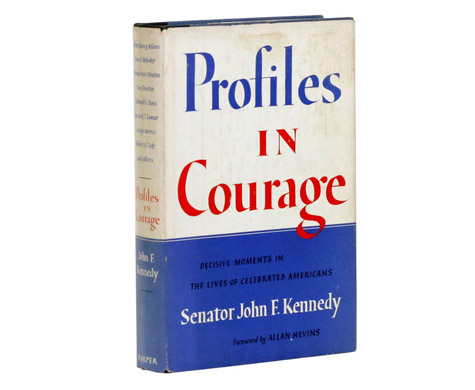

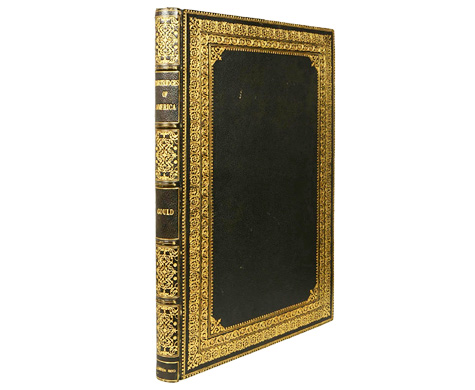

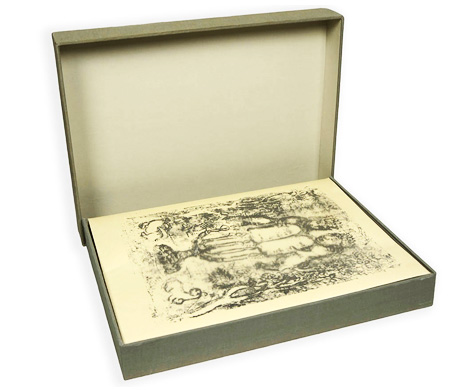

Another 1stdibs dealer, Michael DiRuggiero of Manhattan Rare Book Company, says the book market has split in recent years. “Common used books have completely fallen off, but the true collectibles have soared,” he says, citing a 1922 first edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses in the original jacket for $75,000, and a 1570 first edition of what DiRuggiero calls “the most important book in Western architecture,” Andrea Palladio’s E Quatro Libri, a tome of engravings that has miraculously survived in near-perfect condition (his asking price: $100,000). “A lot of collectors are looking for first editions of their favorite books,” he says, adding: “I read e-books, which surprises people. But if I really like a modern book, I’ll go out and buy it in physical form.” DiRuggerio also observes that people are living with fewer books these days. “They want books around them, but only those that are important to them. It’s the thinning of the herd.”

London dealer Bernard Shapero, who runs Shapero Rare Books and Shapero Modern in London’s Mayfair neighborhood, sells rare books of any age. “They could be 1490 or 1990, as long as they’re rare,” he says. Shapero finds the market for his wares unaffected by new distribution technologies. “We are no more affected by the existence of e-books than art dealers are by color photocopies,” he says. “The beautiful book is a beautiful object, beyond utilitarian usage.” Tastes change frequently. “At the moment, the market is very strong in areas where people are making money: finance and technology,” Shapero says, mentioning a first-edition of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations from the 1770s as one particularly sought-after tome, now worth about $200,000.

“We are no more affected by the existence of e-books than art dealers are by color photocopies,” says London rare-book seller Bernard Shapero.

No matter what course technology takes, there will still be some who have libraries built specifically to house their book collections. Architect Pennoyer has been “lucky enough,” he says, to design a few, including a working library for the Blumka family on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. Fourth generation art dealers in medieval, Renaissance and Baroque works of art, they needed a purpose-built room to house their prodigious collection of reference books. Pennoyer gave them one, with floor-to-ceiling windows and mahogany paneling with neoclassical details inspired by an actual Renaissance library table that sits in the middle of the room. For Louis Auchincloss, the late New York laywer who wrote some 60 works of fiction and non-fiction, Pennoyer’s firm built a house in the Catskills with the simple feeling of a century-old Swedish barn. “The author’s study was the heart of the house,” says Pennoyer, with a book-lined circular balcony above and an oculus in the ceiling.

When designing the Catskills retreat of prolific author Louis Auchincloss in 1990, architect Pennoyer created this oculus-lit, book-lined space as the upper portion of the writer’s two-level study. Photo by Langdon Clay, courtesy of the Vendome Press

Over the past three decades, interior designer Jayne has amassed some 5,000 volumes about American cookery from the 18th century to the present. “We had too many to fit into a conventional apartment, so we had to buy a loft,” Jayne says with a laugh. He and his partner, Rick Ellis, called upon architect Elizabeth Hardwick to design a system of bookcases that effectively serves as architecture to partition space in their Soho loft, with roller shades to protect the books from the sun.

For as long as there are those like Pennoyer and Jayne and their clients, books are unlikely to become, like typewriters and vinyl records, merely quaint retro collectibles. And as for Workstead’s Brechbuehler, she’s no fan at all of electronic devices for reading. “Technology is hijacking our minds,” she says. “Books represent a desire for slowing down the pace and doing things more calmly.” Besides, she says, “I like to turn paper pages.”