August 10, 2025The incredible popularity of the HBO series The Gilded Age is only one of the many reasons people are currently obsessed with the elaborate fashions and opulent interiors of the late-19th century. Another is the show now on view in London, “The Edwardians: Age of Elegance,” at the King’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace. There, the rooms are filled with visitors oohing and aahing over emeralds and diamonds, couture gowns and charming family-pet portraits in both oil and hard stone.

Running through November 23, it is the first exhibition devoted to those treasures in the Royal Collection (possessions of the British monarchy) that were assembled between 1860 and 1920. The more than 300 pieces on display, half of which have never been shown, were gathered from the private royal residences where they normally dwell.

“The Edwardian era is seen as a golden age of style and glamour, which indeed it was, but there is so much more to discover beneath the surface,” says Kathryn Jones, the senior curator of decorative arts at the Royal Collection Trust. “This was a period of transition, with Britain poised on the brink of the modern age and Europe edging towards war. Our royal couples lived lavish, sociable, fast-paced lives, embracing new trends and technologies,” such as electricity, cars and photography.

Most historians define the Edwardian age as beginning with the accession of King Edward VII, in 1901 (following the 63-year reign of his mother, Queen Victoria), and concluding with the start of WWI, in 1914. The exhibition, however, spans the period between Edward’s wedding to Alexandra of Denmark, in 1863, and the end of the war, including the early years of the reign of their son King George V.

King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra (who ruled from 1901 to 1910) and King George V and Queen Mary (1910 to 1936) were among Britain’s most fashionable couples. They collected everything: jewelry, paintings, silver, ceramics, photographs, books and fashion, by the most celebrated makers of their era, including Cartier, Tiffany & Co., Fabergé, Garrard and William Morris.

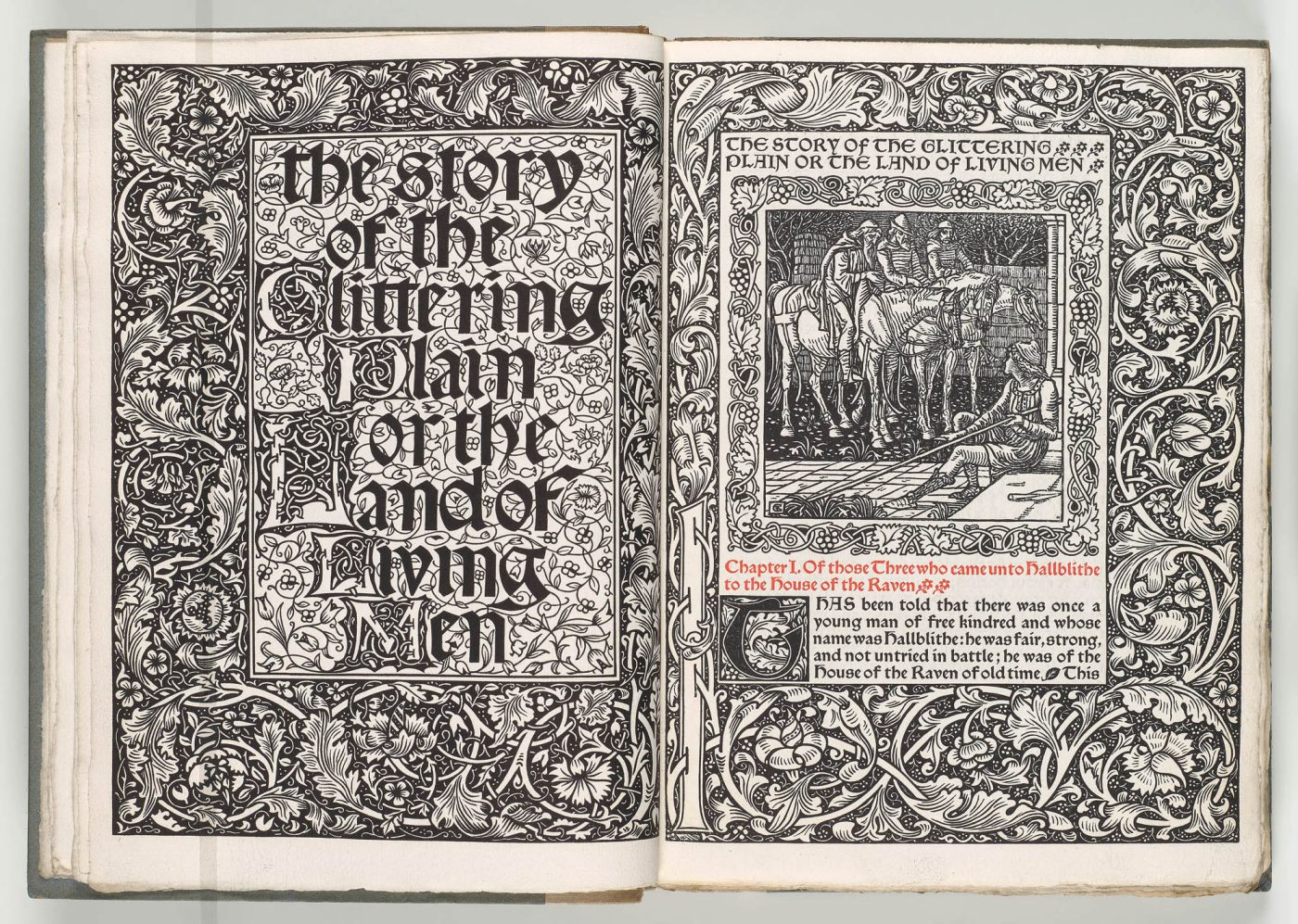

They also bought books of poems by Oscar Wilde and art volumes printed at the Kelmscott Press, founded by Morris and known for avant-garde illustrated editions of classics, like The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer: Now Newly Imprinted, which boasts an original Morris typeface. And they commissioned portraits by society painters Franz Xaver Winterhalter, John Singer Sargent and Philip de László. “Making the selection of items was the most difficult part,” Jones says. “It took three years.”

As Prince and Princess of Wales, from their marriage in 1863 until 1901, Edward (Bertie) and Alexandra (Alix) had a lot of free time, since the mourning widow Queen Victoria continued to hold the throne.

In contrast to the reclusive Victoria, they loved visiting artists’ studios. They even enlisted the painters Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema as artistic advisers. (Alma-Tadema later helped with the decor for Edward’s coronation, in 1902.) The show contains several colorful paintings by the Pre-Raphaelites Edward Burne-Jones and John Everett Millais.

The pair loved porcelain and ceramics, acquiring services from Staffordshire, Sèvres, Royal Copenhagen, Meissen and Wedgwood. They ordered contemporary furniture from François Linke and Morris & Co. and couture gowns from Paris.

“Like Queen Victoria, they invited musicians and artists to court,” Jones says, “but what was new was including actresses, making them acceptable in the royal circle.” The show includes a glass screen with cartes de visite and photos displaying the couple’s favorite celebrities.

We know about their aristocratic lifestyle — the garden parties, theatrical outings, fancy dress balls, shooting parties and regattas like Cowes Week — from such books as Clive Aslet’s The Story of the Country House and Vita Sackville-West’s The Edwardians.

Less has been written about why the prince might have sought out such escapes. As Jane Ridley explains in her excellent 2013 biography, The Heir Apparent: A Life of Edward VII, the Playboy Prince, Queen Victoria considered her heir apparent, Bertie, “unfit to be king,” so she never taught him about his royal responsibilities.

Bertie, Ridley contends, had a lonely, loveless childhood. “I had no boyhood,” she quotes him as saying. He may have compensated by collecting fabulous objects, but, Ridley writes, he lacked “intellectual curiosity.” He did embrace hunting (he killed 28 tigers and an elephant on one tour of India), as well as golfing, gambling and horse racing — and he took on some 50 mistresses. The prince had “strong animal passions” and was “fond of good living,” Ridley writes. “He was the first gossip column prince,” aka Edward the Caresser. “He was addicted to celebrity.”

Some of his affairs lasted years. In 1898, he fell for Alice (Mrs. George) Keppel, with whom he remained friends for the rest of his life. Dubbed “La Favorita,” she was an aristocrat and society hostess (she was also the great-grandmother of Queen Camilla, who was King Charles III’s mistress before their marriage).

One of the showstoppers in the exhibition is a Fabergé cigarette case Keppel gave Bertie in 1908. Embellished with royal-blue enamel, it features a sinuous, diamond-set snake that winds around the front and back, biting its tail in a symbol of unbroken and everlasting love. After King Edward VII’s death, in 1910, Queen Alexandra, who was tolerant of her husband’s affairs, returned it to Keppel. In 1936, Keppel gave it to Queen Mary, to ensure it would remain in the Royal Collection — and, amazingly, the queen accepted it.

Another surprise is that Bertie, the playboy prince, changed his stripes somewhat when he became king. Edward VII turned out to be a hard-working, popular head of state. Ridley writes that he “never left anything to the next day,” toiling deep into the night.

Edward became known as “the welfare monarch,” pioneering charity work and promoting housing for the poor. He cut ribbons, opened bazaars, planted trees and laid foundation stones. He invented the Order of Merit to honor army and navy officers and civilians distinguished in the arts, sciences and literature. The OM remains the most distinguished order in Britain today.

Edward was decidedly against anti-Semitism, welcoming the Rothschilds and Sassoons into society as friends (they were also important financial backers). And he condemned the czarist pogroms against the Jews in Russia, “showing,” Ridley writes, “a moral courage lacking among his ministers.”

A longtime Francophile and a passionate collector of all things Napoleon, among them a fine silver teapot included in the show, Edward visited France often and is credited for personally engineering the 1904 Anglo-French détente. “In foreign policy, he exercised influence and powers that none of his predecessors had dreamed of,” Ridley writes.

The king was deeply attuned to the dynastic rule of Queen Victoria’s extended family in Europe. He wrote his cousins often and attended their weddings and funerals in Russia, Denmark, Norway, Austria, Germany and Greece. These ties expanded the international nature of the king and queen’s collecting.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Bertie’s son George was completely unlike his father: unsocial, not charming, faithful to his wife, utterly domestic. In her 2022 biography, George V: Never a Dull Moment, Ridley writes that he was a “simple man with a categorical sense of duty.” He could be modest but also “gruff and bad-tempered.” He suffered from mood swings and depression.

And he was a lightweight. As his biographer Harold Nicholson writes, “For 17 years he did nothing at all but kill animals and stick in stamps.”

But his marriage in 1893 to his beloved Mary of Teck — aka Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, the daughter of penniless German princeling Franz Teck and known to family and friends as May — seems to have made him focus on royal obligations. “Their new court was neither glamorous nor racy,” Ridley writes.

Nonetheless, May had a passion for collecting. She visited museums and art exhibitions and was interested in history, genealogy and the possessions of the royal family, particularly its jewelry, much of which is in the show.

As we learn from Ridley’s biographyof George V, Queen Mary did not know until her cherished brother Frank’s death, in 1911, that he had left the prized Teck family emeralds to his mistress, Nellie Kilmorey. Determined to get them back, Mary persuaded Kilmorey to sell them to her for 10,000 pounds (one million pounds in today’s money). The jewels are among the highlights of the exhibition, which also contains several paintings depicting the queen displaying her fabulous emerald and diamond necklaces on her ample bosom.

George, for his part, collected the marine paintings of Eduardo De Martino, as well as objets d’art like gold boxes. He also commissioned charming miniature Fabergé hard-stone sculptures not only of the family’s favorite horse and dog but also of a prized Norfolk sow and a number of other farm animals.

Not long into George’s reign, however, World War I dampened tastes for luxury and grandeur, and the glamorous Edwardian age drew to close. But as demonstrated by this exhibition, its style still dazzles.