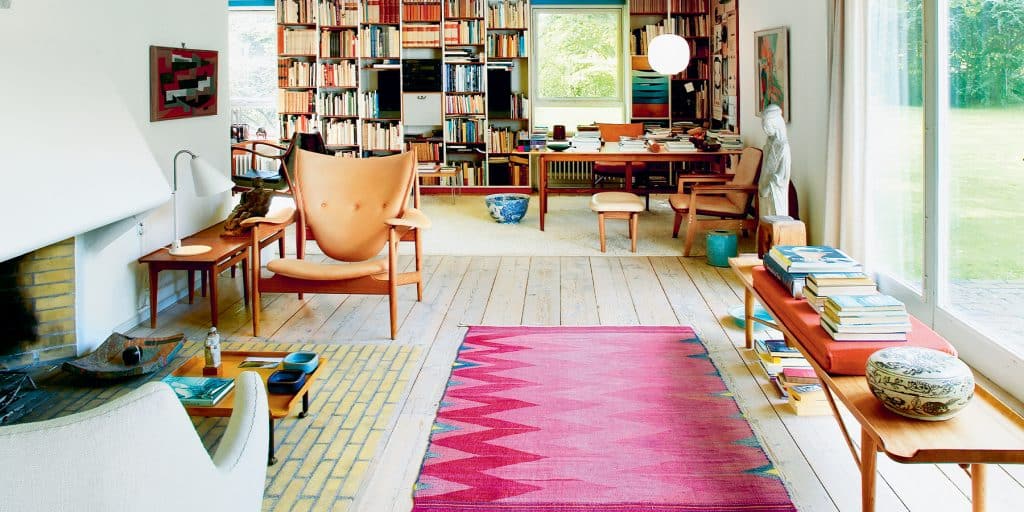

August 18, 2019Mid-20th-century Danish modern architect and furniture designer Finn Juhl — seen here with his dog Bonnie in front of the family home he designed in 1942 in Ordrup, Denmark — is the subject of a new book being released next month by Phaidon (photo courtesy of the Royal Danish Library). Top: The house is now part of the Ordrupgaard Museum, which will reopen next year following renovations. One of Juhl’s Chieftain chairs sits near the fireplace. All photos by Hans Ole Madsen unless otherwise noted

If one person can be credited with igniting the Scandinavian design movement that swept like wildfire across the United States in the 1950s and ’60s, it is Finn Juhl. Before November 1948, when a lengthy article about the Danish architect and furniture designer appeared in Interiors magazine, few Americans had seen the work being produced by a coterie of Nordic talents whose form of modernism was more down-to-earth and approachable than that of their predecessors from Germany’s Bauhaus school. Although furniture by the Finnish Alvar Aalto and the Swedish Bruno Mathsson had been available in this country since the 1930s, its spare lines and laminated blonde woods were nothing like the seductively molded forms and richly grained imported rosewood and teak of Juhl’s pieces. Among his cohort, which included Hans Wegner, Børge Mogensen and Ole Wanscher, Juhl was the only one untrained in cabinetry. That explains the distinctiveness of his designs, which are invariably described as more like sculpture than furniture. As he once acknowledged, “Art has always been my main source of inspiration.”

Juhl’s 45 armchair is one of his early masterworks. It was acquired by New York’s Museum of Modern Art shortly after its 1945 debut, and it subsequently won a gold medal at the 1951 Triennale in Milan. Photo by Laura Stamer

Juhl and his work are back in the spotlight these days, thanks to a new monograph by Christian Bundegaard being published next month by Phaidon. The appropriately titled Finn Juhl: Life, Work, World is a comprehensive treatment of both the designer’s career and the context in which it developed. It includes fascinating archival photos and original watercolors, as well as photographs of Juhl’s interiors, furniture and exhibition designs and a complete inventory of his work and awards. As the book makes clear, he did much more than design furniture.

The monograph is part of a trend of heightened interest in Juhl — who died in 1989 at the age of 77 — that has been demonstrated worldwide in the past few years. Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum mounted a Juhl retrospective when it reopened in October after a five-year renovation; his zig-zag-legged Grasshopper chair, a relatively early work, has lately been reissued; in New York, the United Nations Trusteeship Council interior was restored to reflect the ambience of his original 1952 design; and in late 2016, a ski chalet hotel outfitted entirely in Juhl furniture and named for the designer opened in Nagano, Japan. Add to this some impressive auction results for his furniture, such as the record-setting £422,500 (then about $674,099) fetched by a superb example of his 1949 Chieftain chair a few years back at Phillips London.

Juhl would replace pieces of furniture in his house as he designed new ones. This photo shows it just before the museum took ownership in 2008, nearly two decades after Juhl died.

Born in the Frederiksberg area of Copenhagen in 1912, Juhl originally wanted to be an art historian, but his father pushed him to become an architect, a profession in which he would be more likely to earn a living. So, at 18, he enrolled at Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi (the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts) to study under Kay Fisker, who had taught Arne Jacobsen a decade earlier. While still at school, he worked in the studio of renowned architect Vilhelm Lauritzen, where he was put in charge of interiors.

Juhl produced his first furniture designs for his own student apartment. “I’ve never seen such ugly pieces,” he told a New York Times reporter in 1954. He soon taught himself to do better, believing that furniture was an important part of an architect’s brief. “When I build a house,” he explained to the Times, “I don’t like anyone else to come in and spoil it.”

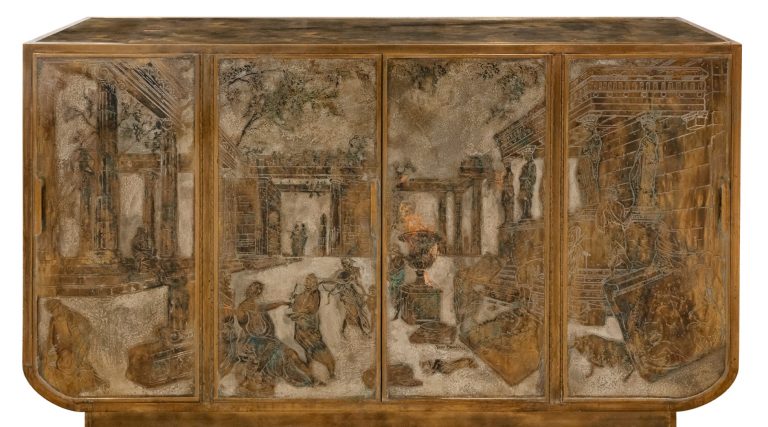

After an article on Juhl and his work appeared in the U.S.-based magazine Interiors in 1948, he began receiving American commissions. Baker Furniture asked him to design for the firm, and he produced a collection of chairs, tables and cabinets and, later, the 1957 sofa seen in watercolor drawings here. Photo by Pernille Klemp

In contrast to some of his function-conscious contemporaries, Juhl approached furniture design like a sculptor. Still, he never forgot its purpose. “Furniture is not created just to be looked at,” he once said. “People should be able to use a piece of furniture.”

Juhl’s early designs were mostly upholstered pieces, like the quirky double-coil-back Pelikan lounge (1940) and curvy Poet sofa (1941). In time, however, he became more interested in wood-framed ones. The 45 chair (1945), one of his most admired designs, was immediately acquired by the Museum of Modern Art and later won a gold medal at the 1951 Triennale in Milan.

From 1950 to 1952, Juhl designed the United Nations Trusteeship Council chamber. It is seen above following a 2013 restoration.

The Chieftain chair (1949) — a grand-scaled armchair whose leather seat and high back are suspended within an open wood frame — is surely Juhl’s most distinctive and sought-after piece. “There’s little doubt these works of pure sculpture came from the mind of a brilliant artist,” says New York interior designer David Scott, who mixes iconic vintage Scandinavian pieces with contemporary furniture to great effect throughout his residential projects. Original editions continue to bring six figures at auction, and even the production versions — made by France & Company in Denmark and Baker Furniture in America — sell for thousands of dollars.

This sketch depicts the stand Juhl designed to display work he created with furniture maker Niels Vodder at the Copenhagen Cabinetmakers’ Guild fair in 1940. Shown in the drawing are the Pelican chair and specifications for wallpaper and decorative objects, including a bow and arrow. Photo by Pernille Klemp

As for that Interiors article — which was written by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., then the director of MoMA’s industrial design department (and whose parents famously commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design Fallingwater) — it both introduced Juhl to America and brought him work. Kaufmann commissioned Juhl to create the exhibition design for, and contribute pieces to, the 1951 edition of the Good Design shows he organized for MoMA and Chicago’s Merchandise Mart. And with Kaufmann’s encouragement, Baker asked Juhl to design a collection of chairs, tables and cabinets, which were described in the New York Times as having “plastic, sculptural lines” and a “floating look.” They debuted at Bloomingdale’s in 1952, bringing Juhl to a much broader audience.

Meanwhile, Juhl continued to work in Denmark, out of the Copenhagen office he had opened in 1945. He did architectural projects, including several stores for Danish silversmith Georg Jensen, whose 1954 50th-anniversary exhibition, which later came to the States, he also designed. In addition, he created 33 SAS ticket offices and terminals in Europe and Asia, as well as the interiors of the airline’s planes.

The seeds of Scandinavian style that Finn Juhl sowed took root and spread in America. He and his work featured prominently in the landmark show “Design from Scandinavia,” which opened in 1954 at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and traveled to 24 museums in the U.S. and Canada; over three years, it was seen by more than a million people. Bloomingdale’s staged a storewide exhibition of Scandinavian design in 1958, by which time other retailers were featuring Nordic furniture and Scandinavian specialty shops were popping up across the country. The aesthetic came to be applied to mass-produced, accessibly priced house furnishings of all kinds.

The 48 chair — a detail of which is shown here — is among the Juhl pieces that have been released by the House of Finn Juhl since 2001. (Many are available on 1stdibs through the gallery DADA.) That’s when the designer’s widow, Hanne Wilhelm Hansen, gave permission for furniture to be produced from his original drawings in contemporary editions. Photo courtesy House of Finn Juhl

Scandinavian style was sidelined in the 1970s and ’80s by an explosion of innovation from Italy, but as the century drew to a close, the fashion cycle came full circle, and Nordic design has enjoyed a revival, which unfortunately Juhl did not live to see. He died in the simple modern home he had designed for his family in 1942 outside Copenhagen. The unpretentious single-story building, furnished with many original versions of his work, had served as a testing ground for his furniture. In 2008, it became part of Ordrupgaard Museum, which is currently undergoing a renovation and will reopen next year.

In 2001, Juhl’s widow, Hanne Wilhelm Hansen, granted permission for furniture to be produced from his drawings, and the House of Finn Juhl has since introduced or reissued more than 40 of his classic designs. (Many are available on 1stdibs through the gallery DADA.) Some of these have intricate frames that were originally too difficult to make. During his lifetime, Juhl had accepted that his designs were challenging. “Perhaps they will be revived some day in the future,” he noted presciently, “when the time is ripe.”

It seems that time has arrived. And now, those who knew only the designer’s name can better appreciate the full range of his talents — and his importance to modern design.