Interior designer Glenn Gissler has long been a collector of objects ranging from silver to fine art to basaltware; for the past three decades, he has steadily been bequeathing items he’s amassed — a selection of which is seen at top — to the museum at the Rhode Island School of Design, his alma mater. All photos by Gross & Daley except where noted. All museum object photos by Erik Gould, courtesy of the RISD Museum

July 20, 2015To the question, “Why do you collect?” interior designer Glenn Gissler has a very simple answer: “Let’s start with the fact that I can’t help myself. You can be a collector of shells or postcards,” he says. “It’s just an impulse you have.” Gissler’s own impulse to accumulate revealed itself early in life, when he began gathering objects such as those mentioned above. But, he observes, “In terms of more ‘grown-up’ things, I would say it started in high school, with architectural fragments.”

His habit escalated, as these things tend to do, and today, says Gissler, he collects Christopher Dresser tableware items; basaltware; Russel Wright dinnerware in three different colors; works on paper by Frank Stella, Conrad Marca-Relli, Joan Mitchell, Alfred Jensen, Donald Judd, David Dupuis and Donald Baechler; and photographs, “mostly older works by my brother Gary Gissler,” he says. “And I have some glass, some silver, lots of ceramics and on and on.”

Not surprisingly, this impulse to collect also manifests itself in Gissler’s interiors, which are anything but minimalist but always feel purposefully curated. “I think of what I do as a form of portraiture,” he explains. “I try to take the clients’ values — where they came from, the origin of their family — and see where they want to be. It’s all through my filter, but with them in mind.” Gissler, who possesses a promiscuous curiosity, presents his clients with many options. “They’re having some visceral response to the objects they ultimately select,” he says, “whether it’s a bowl that costs ten dollars or ten-thousand dollars.” This often leads to intriguing assemblages: In one residence, an apartment near New York’s Lincoln Center, works by Joan Mitchell and Edward Burtynsky share space with Tantric art, French 1950s furniture, Arts and Crafts pottery and a Katanga cross from Zaire.

This distinctive style has earned him no shortage of recognition. Gissler has consulted for Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell as well as Kelly and Calvin Klein and has designed two residences apiece for Caroline Hirsch (owner of Caroline’s Comedy Club) and Michael Kors. He’s landed on top designer lists in both House Beautiful and New York and his work frequently is featured in the likes of Town & Country, Elle Décor, Interior Design and Avenue, among other publications.

In a 10-room apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, Gissler mixed traditional furnishings, including a circa-1900 Sultanabad carpet and deeply upholstered armchair, with standout 20th-century and contemporary pieces that are, in his words, so distinctive “they approach the level of fine art.” These include a Frank Gehry Wiggle chair and Herve van der Straeten Tornade lamp.

In Gissler’s own Brooklyn Heights home, the mantlepiece — arrayed with Robert Mapplethorpe‘s iconic photo of Patti Smith, an antique African mask, a 19th-century Christopher Dresser candlestick and a 1970s abstract glass sculpture — represents a microcosm of his diverse collection.

Gissler’s wide-ranging tastes might verge on the obsessive were they not productively channeled. Fortunately, he has found a new outlet for his acquisitive inclinations: the museum at his alma mater, the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), in Providence. When he was attending RISD — from which he graduated with degrees in fine art in 1983 and architecture in 1984 — its museum already had an impressive collection of painting, sculpture and decorative arts, but very little modern and contemporary design. Gissler decided to remedy that, bequeathing the museum, before he even graduated, a gouache rendering of the Valle’s Steakhouse in Warwick, Rhode Island, that he found in the air-conditioning room of a building.

“They had been collecting for a hundred years,” says Gissler, who recently joined the museum’s board, “but they were operating in a parallel reality. The museum wasn’t a teaching tool at the time. It very much is so now. I thought, ‘Why did I have to graduate from school and then find out who Russel Wright was?’ Students should know this exists, whether it informs their work or not.” Since the gift of the gouache, he has donated more than 200 items. His goal is 1,000 objects, which he hopes will widen the breadth of the museum’s design and decorative art holdings. This sort of zeal led one friend to jokingly accuse him of being “a RISD evangelist.”

Glenn Gissler’s Top 10 Gifts to RISD

Since the mid-1980s, Gissler has been donating objects — in particular, examples of the decorative arts and design — to the RISD Museum, with the eventual goal of bequeathing 1,000 items. Below are a few of what he considers highlights among the some 200 items he’s given so far.

Gissler, who is 57, grew up in and around Milwaukee. “I was precocious,” he says — and you believe him. He is an animated, rapid-fire talker, digressing frequently, though always into interesting tangents. “In 1971, when I was thirteen, I was asked what I wanted to be,” he remembers. “I sat up and said I wanted to be an interior designer.” He takes a rare breath, widens his eyes and lets out one of his frequent chortles. “Where did that come from!?”

His announcement did seem like a bolt from the blue. Gissler’s father was a journalist, his mother a registered nurse. There was no particular design consciousness in the family, though he does recall his father reporting on adaptive reuse of buildings, “which fascinated me.” His explanation for his early vocational dreams? “I was hanging out with people who weren’t normal.” He recalls one friend, at fourteen, bringing into art class his own rendition of Méret Oppenheim’s furry teacup. “However it happened,” Gissler says, “It’s in my DNA; I really don’t have any choice in the matter.”

“I thought, ‘Why did I have to graduate from school and then find out who Russel Wright was?’ Students should know this exists, whether it informs their work or not.”

After graduating from RISD, Gissler moved to New York and worked for Juan Montoya and, later, Rafael Viñoly. “Then Michael Kors asked me to do a ten-thousand-square-foot showroom, studio and office space,” he says. “We had a budget of five cents.” It went well enough, however, that Gissler decided to strike out on his own. “I quit my job and two weeks later — this was October of 1987 — it was Black Monday.” He persevered, plying an eclectic style, not quite traditional and not quite modern, that reveled in what he calls “the power of objects.” One reason his style cannot be easily categorized, he believes, is because the meaning of the term “modern” is itself elusive.

He points to tabletop objects he collects by Christopher Dresser as the perfect example of how thin the line between traditional and modern can be. “Dresser was fairly entrenched in the nineteenth century,” Gissler explains. “He’d make a tile that looked Edwardian, but then he’d make a toast rack that looked kind of Secessionist or Bauhaus. He was using modern industrial capabilities. I find that to be stunning. When did that become modern?” Basaltware is another example: “Some of it is in the genre we know as Wedgwood, very frilly. But some pieces look like they’re Art Deco, even though they were made in the 1820s. I don’t know that in England in the 1820s they were trying to be modern. I love modern. But what is it? I’m interested in where ‘modern’ begins.”

Perhaps not coincidentally, Gissler splits his time between two 19th-century residences: an apartment on two upper floors of a townhouse in Brooklyn Heights and a Greek Revival home on more than eight acres in Litchfield County, Connecticut. “I respect their aesthetic on one level,” he says. “But I like to create a tension in them where there’s one foot in history and one foot in the present.”

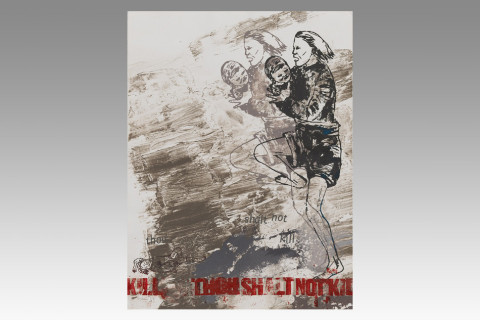

This essentially also describes his criteria for the objects he donates to the RISD Museum. “I’m interested in things that might have been revolutionary then, but still feel contemporary now.” His wide-ranging donations include furniture, textiles, apparel, decorative arts, industrial design and works on paper, and they span from 1820 (basaltware) to 2014 (an Ann Hamilton photograph). Represented are, among others: flatware by Josef Hoffmann, Giò Ponti and Ettore Sottsass; a Peter Behrens toaster; a radio worn like a bracelet made by the Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. in 1969; a 1972 Richard Sapper Tizio desk lamp; a Henry Dreyfuss phone designed in 1936; works on paper by Sol LeWitt, Josef Albers and Alfonso Ossorio; tea sets by Eva Zeisel and Matteo Thun; fashion items by Dries van Noten, Vivienne Westwood and Marni; and textiles by Emilio Pucci, Edward Wormley and Kiki Smith.

“As a donor, you can operate more quickly and stealthily than a curator, who has to follow a whole procedure,” says Gissler. “And curators are not paying attention to twelve different auction houses and what’s online. Because I am, I also know what things should cost. Why should we have to wait for something to become expensive before we collect it?”

Many of Gissler’s donations spend time as part of his personal collection. “I have lived with them for years and learned what I wanted from them,” he says. “Then I’m ready to move on.”