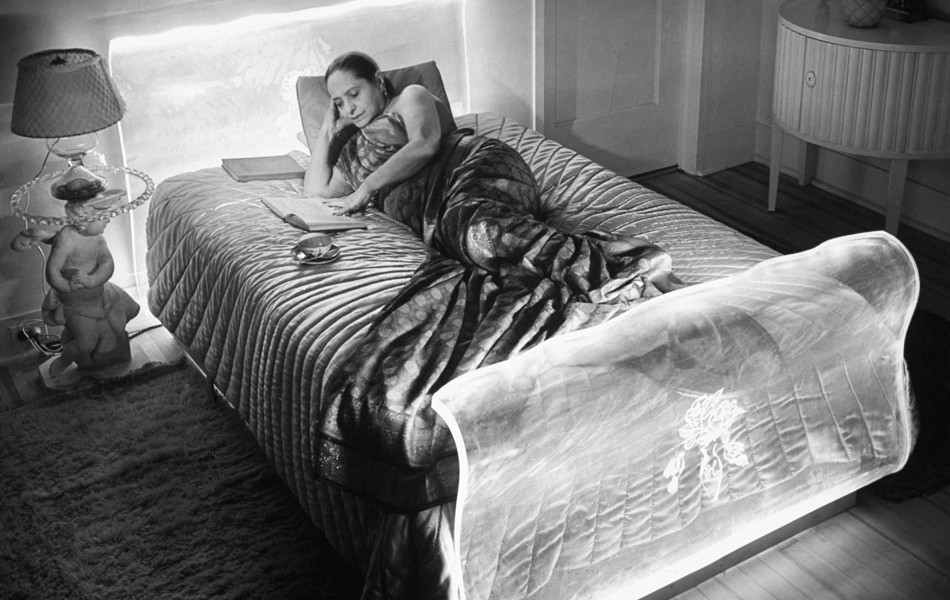

November 2014A voracious collector, Rubinstein acquired art, furniture and objects of all varieties, including African masks, such as the one she’s seen holding here, in 1934, from Ivory Coast. Photo by George Maillard Kesslere

It’s hard for me to say when I became aware of Helena Rubinstein as a collector rather than as the legendary and quite formidable cosmetics tycoon. I was a teenager when Madame, as she was called both professionally and in her personal life, become my step-grandmother. It was 1960 and my mother, Niuta, had married her elder son, Roy Titus. The ceremony took place in the high-ceilinged foyer of Madame’s Park Avenue triplex with its black-and-white checked marble floor, tall arched windows, Indonesian teak furniture (painted white) and numerous marble heads by Elie Nadelman. Polish-born, like she, Nadelman was one of her favorite artists — so much a favorite, in fact, that she bought out his entire exhibition in London after meeting the sculptor in 1911.

Either I was not aware of it at the time, or, more likely, for no apparent reason, I took it all for granted — in retrospect I’m not sure why — but the eccentric mix included a series of African sculptures lined up according to size above the door to the grand wood-paneled living room; Victorian Belter pieces upholstered in surprising purple and shocking pink; tapestries by Picasso and Rouault; a fantastic leafy landscape by Matisse; a couple of Chagalls; and a few Modiglianis, which all seemed arranged in a rather random fashion.

As a young woman in the 1960s, the author (center) made several trips with her mother (right) to visit her step-grandmother in Paris.

It was Roy’s fourth marriage and my beautiful and vivacious, twice-widowed mother’s third. Neither of them were collectors of any kind. My new stepfather — tall, elegant and very cultured — moved into the apartment my mother had lived in for a dozen years with only his bespoke English suits and his beloved stamp albums. He brought nothing with him that would even hint that he was the offspring of a woman who displayed early Picasso drawings alongside beautiful Brâncuși sculptures and Dalí paintings on the walls of her apartment’s 68-by-17-foot top-floor gallery. (That Dalí, by the way, depicted a bejeweled Madame sculpted out of a cliff.) He was not flamboyant like his mother, and, as far as I could tell, he had no interest in collecting art or in being surrounded by possessions at all.

Like his mother, Roy was thrifty. (Until the day she died, Madame would carry her lunch to the office in a brown paper bag, her frugality maybe stemming from her humble beginnings in Poland and her struggles to establish herself as an entrepreneur at a very young age after emigrating to Australia.) But he was also tyrannically punctual and would not tolerate wastefulness of any kind. “Put it away,” I remember him admonishing me, a then typically messy teen. He believed in “a place for everything and everything in its place.” Then, as now, I was more comfortable amid clutter. Decades after seeing the swirling mix of Madame’s possessions, I now realize how powerful her rooms, filled with the most exotic things, were to me — even if the pieces’ origins and significance were then a complete mystery.

“The eccentric mix included a series of African sculptures lined up according to size above the door to the grand wood-paneled living room; Victorian Belter pieces upholstered in surprising purple and shocking pink; tapestries by Picasso and Roualt; and works by Matisse, Chagall and Modigliani, which all seemed arranged in a rather random fashion.”

“Helena Rubinstein: Beauty is Power,” on view at New York’s Jewish Museum through March 22, features around 200 pieces from the Polish-born cosmetics entrepreneur’s diverse collection, including many of the portraits she commissioned of herself. Photo by David Heald © The Jewish Museum, NY

After my mother’s marriage, I was able to visit the apartment a few times over the following years, usually for dinner, before Madame died on April 1, 1965, at the age of 94. The table would be set with turquoise and candy-pink pieces of Opaline glass, literally hundreds of pieces of which were lined up on shelves off the dining room, where about two dozen Mexican Primitive paintings hung on the paneled walls. As soon as she could, Madame would adjourn to the living room or the smaller dining room. There, a card table awaited her for her beloved rounds of bridge; both my stepfather and mother were expert players.

After a visit to her unforgettable Paris apartment, where she often held glamorous receptions and fashion shows, on the Ile St. Louis, with its panoramic view from its extraordinary terrace of Notre Dame, I came to realize that Madame was truly an original, maybe more of an accumulator than a collector — that her eclectic taste and mix of so many different works of art and objects took on a life of their own. Looking through the catalogs of more than 2,000 lots that were auctioned at Parke-Bernet Galleries in New York a year after her death, one can only get a small sense of the vastness and imaginative richness of her possessions.

Over the ensuing years (Roy died in 1989, my mother Niuta in 1995) I often thought of asking my stepfather to explain both his lack of interest in acquisition and Madame’s celebration of obsessive collecting. But I feared that it would stir up too many memories of their difficult relationship, and I suspected his need to distance himself from an unhappy peripatetic childhood.

An installation view of the Jewish Museum exhibition shows an array of small sculptures, both African and European, from Rubinstein’s extensive holdings. Photo by David Heald © The Jewish Museum, NY

After studying art history in London, I returned to New York and quite coincidentally started working as a writer and editor in the field of design and interior decorating. The more houses I visited and the more designers I talked to and wrote about, the more I realized that Madame’s style and verve had become a barometer for me. I was drawn to a mix of high and low, to colorful and unusual pieces and to an excess that came not from a need to show off the number and scope of one’s possessions, but from a lively openness to the myriad possibilities of what art and objects could offer.

From Paris to Mexico City, Madame knew people from whom she could buy whatever she wanted. She exposed her clientele in her salons to works by De Chirico and furniture by Jean-Michel Frank, she bought Indian jewelry, semi-precious stones, and costume pieces by the dozen, and she championed such young (at the time) designers as David Hicks in London and Donald Deskey in New York, hiring them to apply their talents — which she somehow recognized before they become famous — and leave their imprimatur on her various apartments and houses. Like other collectors, she was often well advised (the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, for example, counseled her on buying African sculpture), but she also just did what she wanted.

The author photographed by Meghan Petersen

In beauty, art, fashion and design she was a pioneer. And as a reporter, I marveled at her boldness and bravura. I often think of her when I go to antiques shops and flea markets, one of my particular passions, and something jumps out at me that maybe I’ve never seen before. Drawn especially toward ceramics and pottery, I am not attracted to valuable and rare things, but rather to the discovery of everyday and utilitarian pieces. But not everything, of course: I love color and pattern, craftsmanship and uniqueness. I like objects that were made with imagination and are, well, fun to look at and use. And that can make the basis for a new collection.

When appraisers came to Madame’s apartment after her death to tag the hundreds of artworks, pieces of furniture and objects that were to be auctioned, one of them noted that some things were “bizarre, rather than beautiful.” I love that, and I hope that Madame would have enjoyed my appreciation for her breathtaking extravagances, as well as her personal eccentricities and her love of things, both precious and ordinary, in good taste and not so good taste, that made up her truly singular style.

Suzanne Slesin, left, is the publisher and editorial director of Pointed Leaf Press, which specializes in illustrated books in the fields of interior design, fashion, photography and art. She is the author of Helena Rubinstein: Over the Top, Beauty, Art, Fashion, Design.

More of Madame’s treasures from the exhibition