Interior Design

by Ted Loos

The goal of a good interior design book is not to make you want to tear apart your living room and immediately hire someone to fix it (although, admittedly, that can be a side effect). Rather, it’s to provide inspiration and an understanding of how elements of decor come together in a coherent whole. Tone is the hardest thing to master — friendly and informative is the ticket — and these four volumes have got that just right.

December 7, 2015_dropcap_

A hotel room is properly construed as a home away from home, and that’s why Kit Kemp’s interiors have achieved such renown. Cozy without being drowsy, Kemp’s work — as design director for Firmdale Hotels — emphasizes craft, texture and artistry. In Every Room Tells a Story (Rizzoli, $49.95), written with Fiona McCarthy, she lays out her thinking for projects like New York’s Crosby Street Hotel and a slew of London properties, including the Charlotte Street Hotel.

Cover: Kit Kemp furnished the Suffolk Suite at Haymarket Hotel, in London’s theater district, with a hand-painted 1835 Scandinavian marriage cabinet and two vividly patterned sofas. Right: The same suite also features a sculptural antique breakfront under a modern artwork composed of slices of a cut sponge and a graceful bergère covered in a 19th-century needlepoint fabric. Photos by Simon Brown, courtesy of Rizzoli

Kemp celebrates bold patterns and the quirky elements of folk art, but her interiors never feel busy. And she is inventive. Rooms with perfect exposures, sunshine and gentle breezes wafting in are rare. “With that, who would need an interior designer?” she asks in the “Rooms without a View” chapter and then proceeds to explain how she handled the windowless Dive Bar at London’s Ham Yard Hotel, using a fabric-covered wall and a mud-bead chandelier to soothe the eye. Kemp’s approach is hospitality personified, and well communicated in Simon Brown’s crisp photographs.

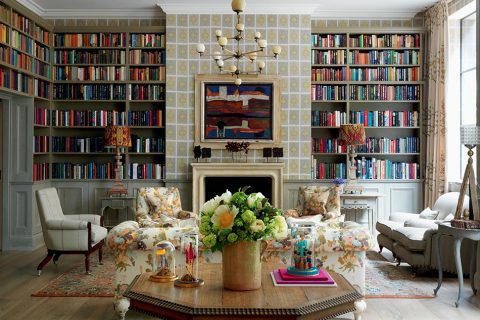

Kemp decorated the library at the Ham Yard Hotel in London’s Soho to look a bit like an invitingly Bohemian-chic English country house. “Brown furniture” commingles with generous upholstered pieces covered in an autumnal rose chintz from Jean Monro, while a bold Leonora Carrington painting bestows a bit of modernist grandeur on the room.

_dropcap_

There is no more storied name in American decorating than Parish-Hadley. For more than three decades, Sister Parish (1910–94) and Albert Hadley (1920–2002) created the proper-yet-comfortable high style often spotted in the tonier precincts of the East Coast (including the Kennedy White House). Now decorators Bunny Williams and Brian McCarthy, who both worked at the firm, have brought out Parish-Hadley Tree of Life: An Intimate History of the Legendary Design Firm (Stewart, Tabori & Chang, $60).

Right: For a family in Virginia, Bunny Williams gave a double-height great room a cozier ambiance by adding rough-hewn beams to the ceiling and arranging the seating around several gathering spots. Photo by Fritz von der Schulenberg

As the title suggests, the book is really an examination of the ripe fruit from the more recent branches of the tree, namely exquisitely tasteful interiors by the likes of Thomas Jayne, Thom Felicia, David Easton and some 30 other Parish-Hadley veterans. After an enjoyable roundtable discussion between the authors, each decorator gets a chapter to reminisce about the firm’s founders and to discuss the bedrock principles of designing. Perhaps the most pleasurable part is learning that the legends were human — did you know that Sister Parish, despite her nun-like name and WASPy froideur, could be a cutup? Read the book and you will.

A painting by the Paris-based Chinese artist Tianbing Li greets those entering this New York townhouse, designed by Brian Murphy. A Chinese lacquer and mother-of-pearl-inlaid console, flanked by two fanciful French chairs from the 1940s, and a silk Tibetan rug add to the room’s urbane exoticism. Photo by Sergio Villatoro

_dropcap_

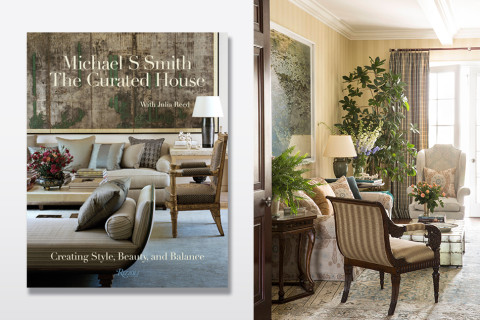

The peripatetic, influential decorator Michael S. Smith appears to be everywhere: designing the Obama White House; fashioning a chic embassy residence in Madrid with his partner, James Costos, the U.S. Ambassador to Spain; gracing the pages of Architectural Digest seemingly every other month. Now comes his fifth book, Michael S. Smith: The Curated House (Rizzoli, $65), written with Julia Reed.

Right: One of the ways Smith added character to the living room of a spec house in Pacific Palisades, California, was by painting a subtle stripe on the walls that harmonizes with its “pretty plaid” curtains. Photo by Lisa Romerein, courtesy of Rizzoli

As Reed notes, Smith is the “consummate Californian,” and as the designer himself adds, “There’s always a little bit of lemon in what I do.” That influence doesn’t come across as beach casual but rather as a style relaxed enough to allow a Richard Serra artwork to hang on the wall over a Louis XIV bibliothèque, as in a Park Avenue apartment featured in the book. Four of Smith’s own residences make it into Curated House, along with 14 others in locations from London to Palm Springs, all with pithy texts by Reed and copious photographs.

For a newly built Spanish Revival house in Santa Monica, California, Smith had the walls hand painted with a crackle varnish finish and then adorned them with an ornate Spanish giltwood mirror and several 17th-century Spanish portraits of Roman generals. Photo by Björn Wallander, courtesy of Architectural Digest, © Condé Nast Publications Inc and Rizzoli

_dropcap_

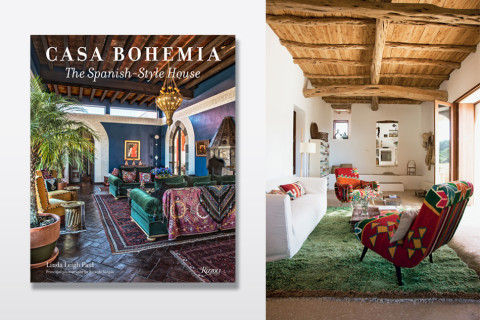

Admirably themed and tightly conceived, Casa Bohemia: The Spanish-Style House (Rizzoli, $55) immediately invites the reader to slow down, settle in and perhaps pour a drink — maybe a fino or a tequila-based cocktail, before a siesta. The book, by Linda Leigh Paul with photos by Ricardo Vidargas, focuses on some 30 homes in Spain, Mexico and the southern United States, some quite old and others brand-new. It tries to capture the essence of a design ethos, beyond just the familiar details of tile roofs, wrought iron and stucco.

Cover: The interior of a Spanish-Moorish-style house in Mexico is filled with rugs acquired by the owners when they lived in the Middle East. Right: Kilim-covered lounge chairs and pillows enliven the living room of an ancient farmhouse renovated by the Catalan textile designer Nani Marquina and photographer Albert Font on the island of Ibiza. Photo by Albert Font

Paul writes that the many variations and cultural influences encompassed by Spanish style make learning about it “an exhilarating adventure.” The book hops around admirably, from a lovingly restored grand 17th-century stone house in Mexico to a fairly modest 1920s Spanish Revival home in Dallas. Emanating from all of them are a warmth and sensuality that no homeowner will fail to appreciate.

It took five years to build the fantasy Moorish tower Casa Ablitt in Santa Barbara, California. More than a year was spent framing and pouring the concrete structure, and then another 44 weeks went into laying its more than 10,000 tiles. But who would argue that it wasn’t time well spent? Photo by Jim Bartsch

Art

by Ted Loos

If an art book is doing its most basic job, it will visually dazzle us. And if it goes the extra mile to illuminate not only paintings and objects but also the people who make them, so much the better. Both aims are achieved by a spate of new releases that are devoted to artists as diverse as Pablo Picasso and Frank Sinatra (what would those two have talked about at a party?) and that tackle subjects as compelling as the representation of the body throughout history.

_dropcap_

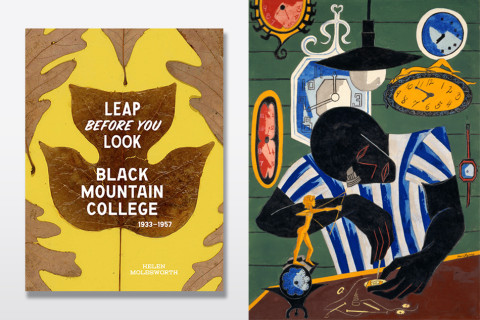

Strikingly designed and weighty, Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933–1957 (Yale University Press, $75) examines a Brigadoon-like educational experiment that burned bright for almost a quarter century but couldn’t last. Authors Helen Molesworth and Ruth Erickson — curators of the exhibition of the same name currently at the ICA Boston until January 24, when it will then tour the country — have delved deeply into the history of the unconventional North Carolina art school.

Cover: Leaf Study IX, ca. 1940, by Josef Albers (© Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society/New York, photo by Tim Nighswander/Imaging 4 Art). Right: Watchmaker, 1946, by Jacob Lawrence (© The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Artists Rights Society/Seattle, courtesy of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, photo by Lee Stalsworth)

Black Mountain’s faculty included, at various times, Josef and Anni Albers, Elaine and Willem de Kooning, Merce Cunningham, John Cage and a host of other towering names in 20th-century art. The book makes much of the art these top talents created at the school, and rightly so. But in essays by a long list of contributors, the reader can also learn about the work of stage designer Xanti Schawinsky and other lesser-known artists who were also boldly and freely experimenting in the way that the school famously encouraged.

Buckminster Fuller inside his Geodesic Dome, 1949. Photo courtesy of The Estate of Hazel Larsen Archer and Black Mountain College Museum and Arts Center

_dropcap_

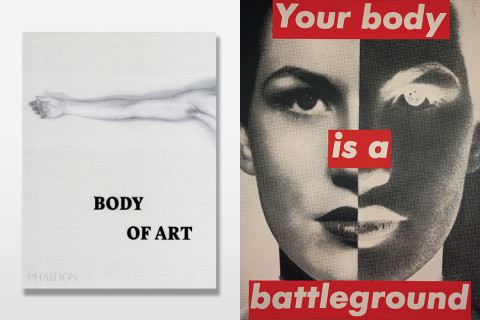

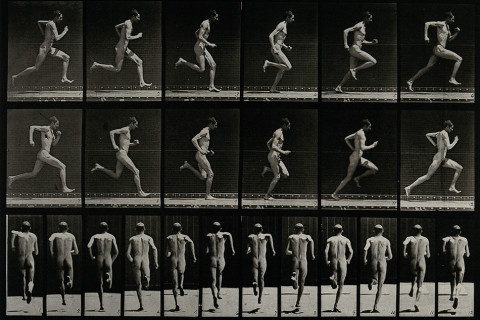

A true coffee table book allows the reader to open to a random page and immediately get a jolt of recognition or pleasure. Body of Art (Phaidon, $60), which explores depictions of the human form over the millennia through 450 works, is just such a tome. Almost every two-page spread offers a thought-provoking juxtaposition: contemporary photographer Catherine Opie with Austrian legend Egon Schiele, both depicting legs at a similar angle; Surrealist great René Magritte with 16th-century Dutch painter Joos van Cleve, both representing breasts — one surreally, the other admiringly.

Cover: A detail of a Robert Mapplethorpe photograph. Right: Untitled (Your Body Is a Battleground), 1989, by Barbara Kruger (The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica, California, courtesy Sprüth Magers)

The book, compiled by Phaidon editors, makes a real attempt to be more than a greatest hits collection. It’s arranged thematically, with chapters on topics like “Religion & Belief” and “The Body’s Limits.” Guggenheim curator Jennifer Blessing tees up the project with a short introduction outlining the ambitious scope, and thorough readers who make it to the end are rewarded with an extensive timeline of milestones in body art through the ages.

A Man Sprinting, 1887, by Eadweard Muybridge. Courtesy of Wellcome Library, London

_dropcap_

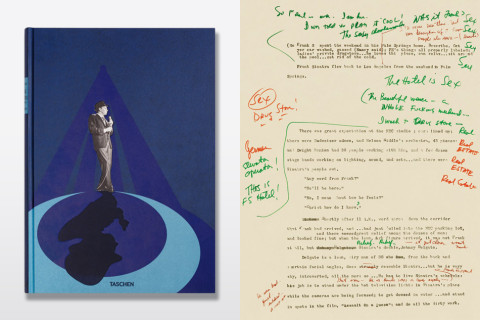

It may sound like one of the year’s oddest book entries, but fans of the New Journalism movement of the 1960s know that Frank Sinatra Has a Cold (Taschen, $200) takes its title from a classic Esquire magazine article by Gay Talese that followed the legendary singer in one of his bluer periods. Taschen has created a lavish tribute to the landmark story, including not only the original text but a new introduction by Talese and a history of its creation. This collector’s edition is signed by the author, with a silk-screened cover and an embossed case.

Right: A page from the first draft of Talese’s famous essay on Sinatra, which the writer describes as “really the fast typing of my notes . . . filled with typos, misspellings and scribblings between the typed lines revealing lots of frustrations and lack of direction.” © 2015 and courtesy of Gay Talese

What’s more, there are dozens of black-and-white images by the photographer Phil Stern (famous for his Marilyn Monroe pictures), who had more access than anyone to Ol’ Blue Eyes over the decades. These eye-popping, behind-the-scenes photos don’t just set the mood; they are as much a chronicle as Talese’s text is. The words and pictures combine to make us feel that we are present for the ring-a-ding-ding of Sinatra at one of his late peaks.

Sinatra, as Nathan Detroit, breaks for lunch while filming MGM’s Guys and Dolls, Los Angeles, 1955. © Phil Stern Estate, courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

_dropcap_

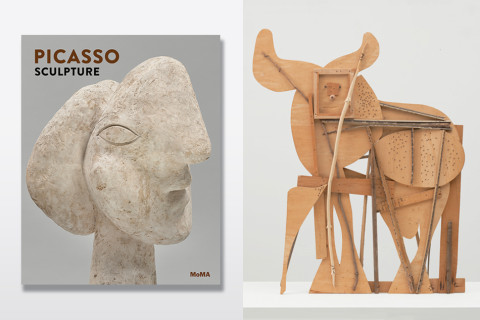

Pablo Picasso as a shape-shifting, protean talent for the ages is now a cliché — but its truth is demonstrated with stunning clarity in the huge exhibition “Picasso Sculpture,” now on view at the Museum of Modern art in New York. The just-published catalogue to the show (MoMA/D.A.P., $85), by museum curators Ann Temkin and Anne Umland, is an essential guide to the three-dimensional work of one of history’s greatest artists.

Right: Bull, ca. 1958, by Pablo Picasso. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, © 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Although Picasso is far better known for his canvases, Temkin and Umland make a good case for seeing his pieces in the round as among his most important, in that they “represent in the extreme the reinvention that characterized his work in every medium. . . . [E]ach return to sculpture brought a fresh start technically and materially.” This is brought home through 500 illustrations, 300 of them in color, of everything from his early attempts at wood carving to monumental late statements like the early 1960s Woman with Hat, improbably made of sheet metal.

Installation view of “Picasso Sculpture” at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Pablo Enriquez, © The Museum of Modern Art

Gardens

by Jane Garmey

As we begin to plot out next summer’s gardens, looking at what the experts have done is among the best ways to get a better understanding of color, shape and texture — those essential building blocks of good garden design. (It’s really no different from designing a room, with a few exceptions — chief among them that plants cannot be moved around as easily as furniture.) Here we look at some recently published garden books, each reflecting a different point of view but all attesting to the ever-improving breadth and variety of American garden style.

_dropcap_

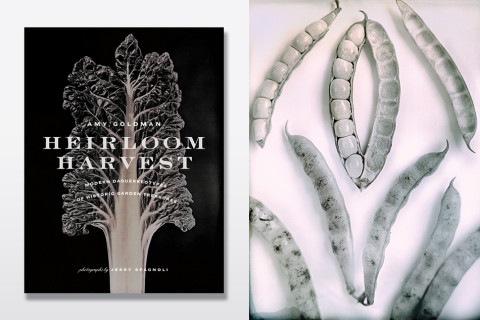

For the past 25 years, Amy Goldman has been growing heirloom fruits and vegetables on her farm in the Hudson Valley. This has been no Saturday afternoon recreational jaunt but a focused, dedicated, intensely serious endeavor to cultivate and enhance the preservation of endangered varieties. During much of this time, photographer Jerry Spagnoli has been recording her work by creating a series of exquisite daguerreotypes, more than 100 of which figure in Goldman’s Heirloom Harvest (Bloomsbury, $85.00).

Cover: Silverado Swiss Chard. Right: Tennessee Cut Short Beans. Photos by Jerry Spagnoli

The luminosity and depth of Spagnoli’s black-and-white images are astonishing. They range from intensely detailed close-ups of pears, apples, gourds and lettuces (to name only a few of his subjects) to larger shots of Goldman’s garden. Add in Goldman’s delightful autobiographical essay and the very thorough botanical index, and you have without doubt the most sumptuous and beautiful garden book of the year.

Armenian cucumber

_dropcap_

Raymond Jungles is the most celebrated landscape architect and garden designer working in Florida today, creating landscapes that are lush, tactile and exotic. He began his career in the early 1980s, and The Cultivated Wild (Monacelli Press, $50), which includes 21 of his most recent projects as well as a brief survey of works now in progress, is his first monograph to appear since 2008.

Right: An informal path leads from the entry gate to the main residence in the Bahamas. Long-platform Florida keystone steps planted with low grass help soften the entry scheme, as do several coconut trees, relocated from cleared land, that have been casually planted amid the flagstones. Photo by Stephen Dunn

The Miami-based Jungles, who considers Roberto Burle Marx his most important mentor, knows exactly how to use native subtropical plants to their best advantage, often choosing species that weave and wrap and form enveloping canopies. Orchids, bromeliads, grasses, succulents and, of course, palm trees add romance to his vision. He is particularly skillful where water is concerned, and dramatic waterfalls and hidden grottoes figure in many of his schemes. But most of all, it is his bold use of color that makes his work so exhilarating.

This penthouse garden overlooks South Beach and South Pointe Park Pier, Miami Beach, into which the pool seems to merge. Photo by Steven Brooke, courtesy of Monacelli Press.

_dropcap_

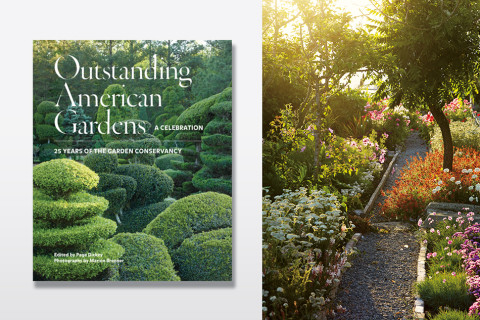

To move from one man’s imagination to the vision of many, turn to Outstanding American Gardens: A Celebration of 25 Years of the Garden Conservancy, edited by Page Dickey and with photographs by Marion Brenner (Stewart, Tabori & Chang, $50). Founded by the legendary Frank Cabot, a financier and self-taught horticulturist who created two of the most celebrated gardens in North America, the conservancy has played a critical role both in preserving gardens of consequence and in encouraging private garden owners to share their work with the public through its very successful Open Days program.

Cover: The Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden in Bishopville, South Carolina. Right: Gardening was one of the few “escapes” available to inmates at the high-security penitentiary on Alcatraz Island, in California’s San Francisco Bay. Flower beds were planted on the path that the prisoners walked to their jobs every day. Photos by Marion Brenner

The book is divided into two sections. The second focuses on a large number of gardens around the country that are featured in the Open Days program. The fascinating first section — which I wish were longer — deals with eight private gardens that have been successfully preserved and are now open to the public. Some, like George Schoellkopf’s English-style garden at Hollister House, in Washington, Connecticut, are well known, others less so. Probably the most unusual is the Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden, in Bishopsville, South Carolina. Begun in the early 1980s and containing more than 300 plants (many rescued from the dumpsters of local nurseries) that have been fashioned into monumental abstracted shapes, it is the creation of Pearl Fryor, an enthusiastic but untrained topiarist whose original motivation was to see if an African-American man could win an award from his local garden club.

The gravel path in the herb garden at Duck Hill, in North Salem, New York, leads to a one-room folly.

_dropcap_

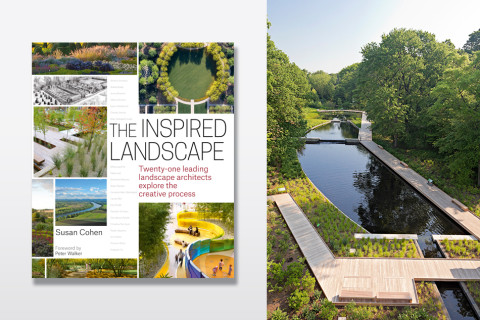

Susan Cohen’s The Inspired Landscape (Timber Press, $50) investigates the creative process of 21 leading landscape European, Asian and American architects through detailed chapters each of which focuses on a single work. The diverse projects range from the redesign of the garden of the American Academy in Rome to a reclaimed industrial park in Duisburg, Germany, to a cancer-care center in Inverness, Scotland, to the new native-plant garden at the New York Botanical Garden.

Right: The native-plant garden at the New York Botanical Garden. Photo by Robert Benson, courtesy New York Botanical Garden

A landscape architect herself, Cohen uses not just photographs but sketches and plans as well to reveal the imagination that fuels the creative process. She is an excellent teacher, and each unrushed chapter helps her readers to better understand the elusive quality of inspired garden design, be it Kim Wilkie’s dramatic earthworks at Broughton House, in England, or Shunmyo Masuno’s meditative gardens at Samukawa Shrine, in Japan.

The VanDusen Botanical Garden visitor center in Vancouver, British Columbia. Photo courtesy Busby Perkins + Will Architects

_dropcap_

For a fascinating slice of garden and architectural history, where better to go than Longue Vue House and Gardens (Skira Rizzoli, $65) by Charles Davey and Carol McMichael Reese. The New Orleans house of the title was designed by William and Geoffrey Platt (sons of Gilded Age New York architect Charles Platt), and its gardens were planned by landscape architect Ellen Biddle Shipman. The clients were a local couple, Edgar and Edith Stern. The estate was opened to the public in 1968 and is now listed as a National Historic Landmark.

Right: The formal dining room at Longue Vue exemplifies the height of fashionable but conservative taste in the 1930s and ’40s. Photos by Tina Freeman, courtesy of Rizzoli

Architects and landscaper collaborated from the start on the project, which spanned from 1935 to ’42, and as a result the style inside and out feels seamless. The Palladian-fronted mansion is built in the Classical Revival style, and the furnishings exude a quiet comfort and old-fashioned elegance. The gardens are traditional, with formal plantings, fountains, terraces, camelia and azalea walks and, this being the South, a marvelous oak allée. The property exudes the ambience and calm of a different age — it’s a piece of design history to be preserved and appreciated.

Dogs

by Trent Morse

Our dogs have become almost as enmeshed in the holiday gifting frenzy as our children have. Alongside the family stockings dangling from the mantel at Christmastime, a sock for Bowser — stuffed with rawhide chews and wearable reindeer antlers, dehydrated pig ears and Santa-shaped squeaky toys — is now the norm rather than the eccentric exception. And although their paws lack the opposable thumbs necessary to twirl a dreidel, Jewish dogs get Hanukkah trinkets, too — just no chocolate gelt. In light of the growing importance of canines in our living spaces and on our credit-card statements, we’ve selected the most stylish art and design books that celebrate man’s best friend (or mama’s little monkey face) on every page.

_dropcap_

One day Cristina Amodeo sat on her dog in the dark, mistaking the poor thing for a piece of furniture — and the idea for a book was born. “The comfortable shape, the soft coat and the proud posture, standing erect on all four legs, were identical to the chair beside her,” she writes. That story is the only bit of narrative in Amodeo’s Dogs and Chairs: Designer Pairs (Thames and Hudson, $14.95), which is otherwise filled with spreads showing her bold graphic illustrations of iconic seating by the masters of modern and contemporary furniture design on one page and a strikingly similar-looking breed of dog on the opposite one.

Cover: A bulldog nestles in an Eero Aarnio Ball chair, 1963. Right: An Arne Jacobsen Grand Prix chair, 1957, is paired with a Welsh corgi. Images courtesy of Thames & Hudson. Illustrations © Cristina Amodeo

We see an orange and white Eero Aarnio Ball Chair next to a roly-poly bulldog of the same color, an undulating Frank Gehry Wiggle chair paired with a profusely wrinkled shar-pei, the wavy surfaces of a Sori Yanagi Butterfly stool matched with a long-haired Afghan hound. And so on. It’s uncanny.

The folds of a Frank Gehry Wiggle chair, 1972, could only be matched by a shar-pei.

_dropcap_

Unexpectedly, Angus Hyland and Kendra Wilson have organized their sumptuously illustrated compendium The Book of the Dog: Dogs in Art (Laurence King Publishing, $15.95) by breed (dachshund, spaniel, “mixed” and more), rather than chronologically. It turns out to be an engaging format for presenting the myriad ways that artists have depicted dogs over the past three centuries.

Cover: Whippet, 2013, by Sarah Maycock. Right: The Dog, 1820, by Francisco Goya. Images courtesy of Laurence King Publishing

Readers can compare classic portrayals by Francisco Goya, Jean-Léon Gérôme, John Singer Sargent and Edgar Degas with brushier contemporary works by Elizabeth Peyton, David Hockney, François Bard and Grażyna Smalej. Somewhere in between lie the squiggly frolickers of Two Poodles (1891) by noted dog lover Pierre Bonnard, who was always several years ahead of the pack.

Sophie, Boston Terrier, 2010, by Constance Bachmann

_dropcap_

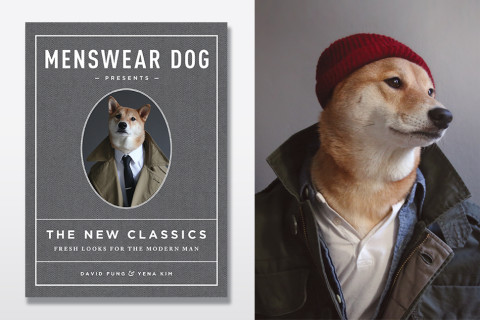

A dog in human clothes is just about the cutest thing ever — doubly so when the outfit mimics a fashionable look. But the adjectives for Bodhi, the Internet celebrity Shiba Inu known as the Menswear Dog, extend well beyond cuteness: He’s a dapper, sophisticated, handsome, rugged, puckish supermodel.

Right: Bodhi likes his military field jacket to be roomy to allow for layers, such as a J.Crew chambray button-up over a Club Monaco Henley shirt. Images courtesy of Artisan. Photographs by David Fung and Yena Kim

In Menswear Dog Presents: The New Classics: Fresh Looks for the Modern Man (Artisan, $16.95), Bodhi — with a little help from his owners, graphic designer David Fung and fashion designer Yena Kim — shows off his remarkable ability to strike just the right pose while sporting menswear essentials for every season and occasion, from a Picasso-esque Breton striped shirt to a Dolce & Gabbana tuxedo. When reading this book, it’s easy to get swept up in the fashion advice — and to forget that it’s coming from a dog.

The outdoorsman style includes a Woolrich buffalo-plaid jacket, a Penguin fisherman’s sweater and Ray-Ban aviators.

_dropcap_

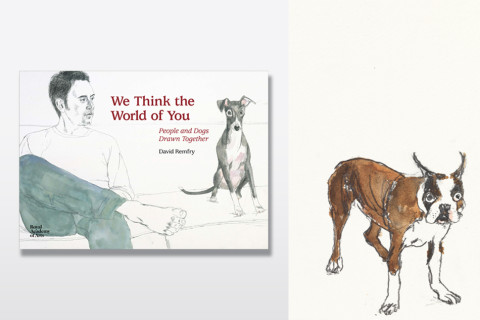

British painter and Royal Academician David Remfry is perhaps best known for his lively portrayals of city nightlife and street scenes. For We Think the World of You: People and Dogs Drawn Together (Royal Academy of Arts, $26.95), however, he puts pooches and their masters under the spotlight. Many of Remfry’s subjects are his neighbors at New York’s notorious Hotel Chelsea, and some have marquee names, like Susan Sarandon, Alan Cumming and Ethan Hawke.

Cover: Geoffrey Firth and Rocco, 2009, by David Remfry. Right: A watercolor and pencil drawing on a postcard, 2013. All images © David Remfry MBE RA

The models (human and canine) recline together on couches or beds to accentuate the closeness between species, which is further emphasized by Remfry’s soft pencil lines and watercolor washes. In one picture of art patron Agnes Gund, we see just her foot propped up on a mattress while her shaggy companions somberly wait for her to recover from a surgery. The illustrations are accompanied by anecdotes about the sitters’ relationships, including Remfry’s own touching remembrance of his German shepherd, Blue.

Ethan Hawke and Nina, 2007. This sitting was particularly difficult for Remfry, since the actor’s dog refused to sit still for long.

Other Stories You Might Like

-

Our Holiday Roundup of Luscious Coffee-Table Books, Part 2

Read MoreIn the second part of our roundup, we offer our favorite new books on architecture, fashion, furniture and jewelry.

-

Travel Plans Canceled? Explore Inspiring Interiors from around the Globe

Read MoreThis comprehensive guide features insider views of fascinating residential designs in 50 countries.