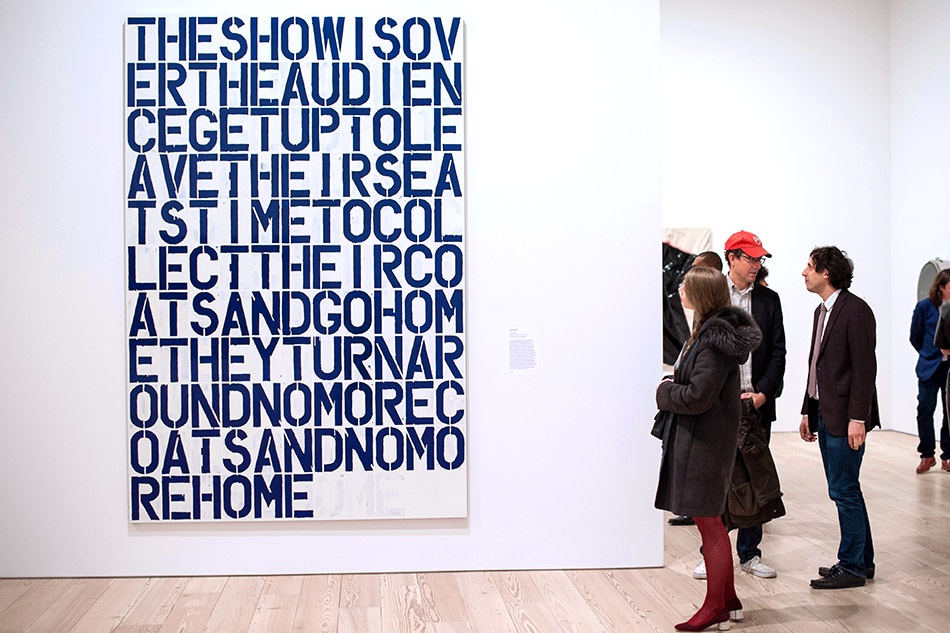

February 1, 2016Christopher Wool‘s Untitled, 2002, is one of hundreds of artworks Thea Westreich Wagner and her husband, Ethan Wagner, recently gifted to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Above: The Wagners in November, on the night of the museum’s dinner to celebrate the show‘s opening. All photos by Matthew Carasella, unless otherwise noted

It’s not uncommon for couples to collect art together. There are Don and Mera Rubell of Miami; Mitchell and Emily Rales of Potomac, Maryland; Hunk and Moo Anderson of San Francisco; and, perhaps most remarkably, New Yorkers Dorothy and the late Herb Vogel, a librarian and a postal worker, respectively, who managed to assemble one of the largest and most important contemporary art collections ever and later donated their accumulated artworks, dividing them among the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., and 50 other museums, one in each state. To help keep the divorce lawyers at bay, many such art-loving pairs devise rules for their acquisitions, such as the need to agree on every purchase.

Not so Thea Westreich Wagner and Ethan Wagner, who recently gifted nearly 550 artworks to the Whitney Museum of American Art, a selection of which is on view through March 6. In their case, such restrictions have never been necessary. The way they tell it, their minds are so in sync that they always concur — not merely on the artists but on the specific works.

Ethan, 74 and bearded, shares an example while sitting in the spacious Soho loft that houses Thea’s art-consulting firm, Thea Westreich Art Advisory Services. About two years ago, the couple stopped by Gagosian Gallery in Chelsea to see a painting show featuring some of the biggest names — and biggest canvases — around. “We typically separate a little bit walking through spaces,” to take in the art independently, he says. “We got to the end of the show, and there was this small Rauschenberg. That was the painting that I liked the best. Later, I said to Thea, ‘Well, what would you take home out of that show?’ She said, ‘The small Rauschenberg.’ And that happens all the time.”

Cult film director John Waters at the show’s opening with Gareth James’s Money stands for limitlessness. Art will too if it lasts too long, 2009.

“It’s remarkable,” adds Thea, 73, trim and chic in a tailored black dress. “It’s just crazy.” Moreover, she says, on the very rare occasions when they do disagree, rather than stubbornly digging in their respective heels, “we yield to one another. We’re just absolutely sure we’re missing something. At least, I am.”

It’s pretty obvious that the Wagners’ passion for one another is inextricably wrapped up in their shared passion for art. Both had begun collecting well before they met in 1990, although Thea had the inside track on the most directional artists of the day. She snapped up future stars Robert Gober, Christopher Wool, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman early. Under her influence, Ethan, a successful public policy consultant, bought a Mike Kelley “Arena” piece — a blanket arrayed with stuffed animals — and a Wool monotype. They quickly combined not only their lives but also their collecting. They can’t even remember the first thing they purchased jointly, but it was well before their 1994 marriage. Ethan speculates it was something by Ellen Berkenblit, known for her long-lashed females and vibrant colors.

“The interesting thing is I don’t feel I can ever get back to collecting without you,” Thea says to Ethan. “I could tell you what I did before very articulately, but when Ethan and I got together, I felt that our eyes and minds were engaging on a regular basis.”

“That’s interesting — not as interesting as what’s going on in Syria — but in the context of our little existence,” Ethan rejoins, “because I think we fell in love very quickly, and we fell in admiration of each other’s minds very quickly. Certainly, on my part, I could see what was intriguing Thea. For me, it required several steps forward from where I had been collecting.”

Alex Israel’s Self-Portrait, 2013 (left), and Cindy Sherman‘s Untitled (portrait), 1975.

Their merged points of view rapidly became what Ethan calls a “scrambled egg.” “We continued to add elements to that scrambled egg. Maybe some bits of bacon.”

“You don’t mind my telling you that that’s a yucky metaphor,” Thea interjects.

“Not at all.”

Thea says, “Our conversations, just dinner conversations — ‘Why did you like that?’ ‘What did you see?’ — ultimately brought us to the same path. It wasn’t that I dominated or that he dominated; it was that ongoing interaction.”

Walking through the Whitney exhibition might reveal threads running through the collection — a cheeky irreverence, a willingness to confront tough social issues, such as AIDS — but the Wagners are hard-pressed to identify a single unifying theme, save that the work is, in Thea’s words, “unique and explicative of that time,” and that it takes part in the broader conversation of art history. The Wagners prefer to collect artists in depth, acquiring four, five or six works indicative of an artist’s creative arc. More than 75 artists and collectives are represented in the Whitney gift. Although the couple collected some established names, like Diane Arbus and Sol LeWitt, they leaned toward emerging artists, often buying works fresh from the studio — without the benefit of hindsight.

Luck occasionally stepped in. “If you’re collecting the art of your time, it’s very serendipitous,” Ethan explains. “You happen to be in Berlin, and you see a monographic exhibition at a gallery that otherwise you would not have seen. You become interested in that artist, and that artist has a couple of friends, one of whom you also find interesting. I don’t know if art history will see it the same way we see it. But when you’re dealing with art of our time, you have to be ready to walk up to the cliff and just jump.”

Danh Vo’s 16:32:15, 26.05, 2009.

As an adviser, Thea has orchestrated the creation of numerous prominent collections many of which were defined by a medium or other strict parameters. When it came to making their own selections, however, the Wagners could ignore boundaries and snap up whatever spoke to them — be it photography, painting, sculpture, installation, representation or abstraction.

Moreover, while a client often hems and haws over a purchase, requiring time to schedule a gallery or studio visit, more time to read Thea’s research and possibly yet more to negotiate with a hesitant spouse, the Wagners, when buying for themselves, can pounce.

Thea admits there were occasions when she fell in love with pieces that she was scouting for clients. “There were lots of times I would hope they wouldn’t buy it, but you still have to try very, very hard [to sell],” she says. “[Legendary dealer] Ileana Sonnabend basically built her collection by buying the things nobody else took out of her shows. Man, it was great.”

Like many contemporary art collectors, the Wagners have relished the opportunity to get to know the creators firsthand. “If the work is interesting and the artist who’s making it is alive and available, why not get to know the mind that made that work of art,” Ethan says. “That’s been rewarding without measure.”

For instance, Christopher Wool, he of the graphically stenciled text paintings, “taught me more about painting than any history class I’ve taken,” Thea says. “Subsequent to maybe 1986, we tend not to agree on certain things about painting, but Ethan and I are deeply affected by his thinking and his ability to express ideas around painting.”

“When Ethan and I got together, I felt that our eyes and minds were engaging on a regular basis.”

A detail in foreground of Matias Faldbakken’s Untitled (Locker Sculpture #01), 2010.

Schmoozing with artists beats just reading about them, Ethan notes. “Art speak is hard sometimes to get our heads around,” he explains, adding that dinner conversations with artists about their practices “give us so much energy” in a way a recondite article in Artforum might not. Says Thea: “My guess is it’s like taking drugs. My guess is it’s no different from cocaine.”

From the looks of it, the artists return the couple’s affection. Dozens showed up at the Whitney’s dinner to celebrate the exhibition opening, including some who weren’t in the show. Doing right by those artists is in part what led the Wagners to begin to seriously consider giving away their collection about a dozen years ago. They didn’t want to open a private museum, as the aforementioned Rubells and Raleses, among others, have done in recent years, sometimes to accusations of vanity. The Wagners had no desire to preserve their collection in an art vacuum; rather, they wanted it to be absorbed by a larger institution, where it could be seen in the context of the history of art. “It’s about the artist,” says Thea. “It’s not about Thea and Ethan. If it’s your collection and your vision, that’s lovely, and we have that in the catalogue. We’re very proud. But the artist is the essence of the collection.”

At the Whitney, she continues, “who knows whether it’s into the basement or into an exhibition? It’s alive, it’s there, it can always be used. History does rewrite itself.”

After the Wagners decided definitively to donate their collection, about five or six years ago, they still had to select the museum. They fantasized about an institution that could give a room to each artist, but realized that goal would fill “two Whitneys.” They had given or promised works here and there over the years, including Deadpan, an early Steve McQueen film, to the Museum of Modern Art, and pieces by Cady Noland and Jenny Holzer to the Whitney. As they were close to finalizing their choice of the latter for the bulk of their collection, they asked its director, Adam Weinberg, and a curator, Elisabeth Sussman, to walk with them through the museum, which back then was in the Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue. Although the Wagners “love” that structure, Ethan says, “our suspicion that that wasn’t the best space for the kind of art we collected was born out.” Weinberg was confident he would get the planned new building by Renzo Piano erected in the Meatpacking District. With the global financial crisis and a lack of unanimity on the board, Ethan admits, “I don’t think I gave it better than fifty-fifty.”

The couple continue to collect and hang new finds in their Soho loft and their house in Watermill, on Long Island.

But Weinberg’s confidence was not misplaced. In late 2012, with new structure under way, the Wagners signed over to the Whitney their American art, giving another 300-plus pieces of contemporary European art to the Centre Pompidou, in Paris, where the exhibition of the Wagners’ collection will travel next.

After Ethan sold his own consultancy, about 12 years ago, he joined Thea’s, managing the business side. For yet more togetherness, the couple coauthored 2013’s Collecting Art for Love, Money and More (Phaidon). Last April, they handed over the advisory business to two employees. Now, Ethan quips, “we’re so busy doing nothing.” They continue to collect seriously and hang new finds in their Soho loft and their house in Watermill, on Long Island. “Thea’s a bit more relentless than I am,” Ethan says of his wife’s gallery hopping.

Asked if they’re sad to see the collection taken down from their walls, Ethan replies, “As much as we love the works that will never again live in our house, we’re engaged with these things that are more current in our collecting, and we’re processing them. We’re saying, ‘This is really rewarding; this, I don’t know.’ We’re not thinking nostalgically.”

Thea adds that the works at the Whitney “are like our children. Our children have grown up; we can’t keep them home anymore. We’re barely holding onto our grandchildren at this point.”