January 30, 2022When Workstead cofounders Stefanie Brechbuehler and Robert Highsmith and their business partner, Ryan Mahoney, met as graduate students at the Rhode Island School of Design, they felt an immediate connection, as if they were fated to come together. They held their individual viewpoints, of course. But their ideas about design were so in sync that they quickly became inseparable.

The origins of their multidisciplinary design firm — which encompasses architecture, interiors, furniture and lighting (sold on their 1stDibs storefront) — can be traced to that time, says Brechbuehler. “We were attracted to the same professors,” she recalls, referring to architects Christopher Bardt and Kyna Leski. “It was about the process of making, the intelligence of making, learning through making.”

Although the team clearly has enormous respect for the history of architecture and design, she says, “we started just making things,” rather than painstakingly absorbing details of aesthetic styles and precedents.

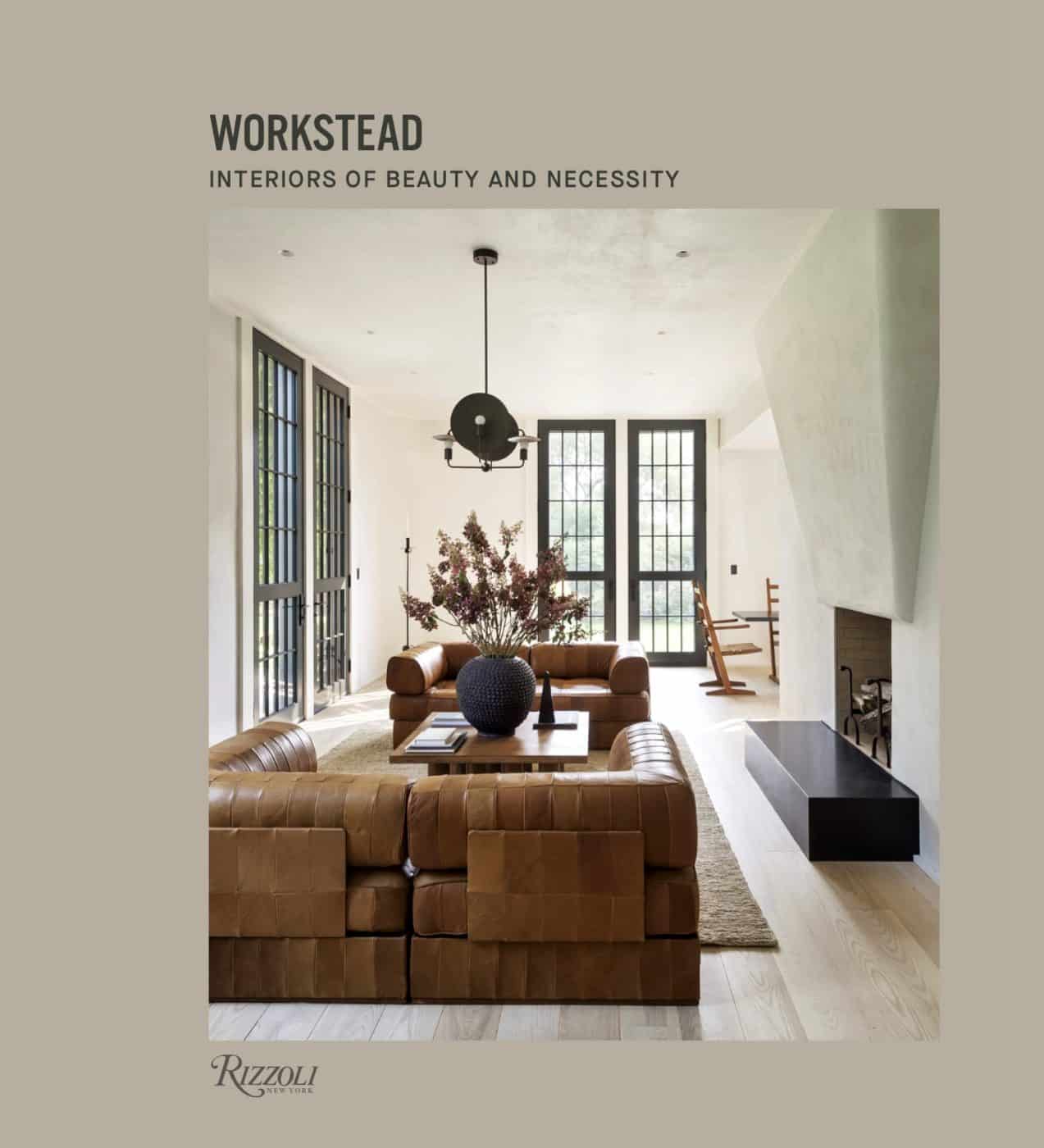

In their recently released monograph for Rizzoli, Workstead: Interiors of Beauty and Necessity, they illustrate how this highly organic way of working shapes both their approach to design and to style. Everything is informed by the need to solve a project’s specific functional needs. The result is unique design solutions, which Workstead brings to life through natural materials, particularly wood.

Custom millwork “was our defining signature before we were even known as Workstead,” Brechbuehler says, referring to the period when the three had their own independent gigs (Brechbuehler working for Michael Graves, Highsmith collaborating with furniture maker Asher Israelow and Mahoney creating sculpture as well as theater sets) — all of which, interestingly, respected the process of making. “We didn’t know better than to design everything from scratch. We didn’t know about IKEA sub-cabinets. We’d make everything.”

In their projects, the three continue to use custom-designed millwork to define spaces in a very fundamental way.

Take the carriage house of a townhouse in Charleston, South Carolina. Today an independent home for the builder who worked on the main residence and his son, the project was first conceived by Workstead as an auxiliary guesthouse. Brechbuehler, who spearheaded the project, loved the structure’s interior walls of brick and crumbling plaster.

“Out of respect for them, I was not going to have any drywall,” she says. Instead, she designed cabinetry in the dining area made of cane (a breathable solution for the Southern heat) framed in fragrant cypress, creating a harmonious architectural envelope for the space that also accommodates a window seat. Where there were no aged brick walls, horizontal slats of cypress panel the rooms. The result is an olfactory experience throughout, as well as a visually all-embracing one.

Brechbuehler complemented the warmth of the brick and caned cabinetry walls in the dining room with an American 19th-century heart-pine table surrounded by the sort of English Glastonbury chairs one might find in a church. Atop the table is a 20th-century cast-concrete garden vessel.

In a townhouse in Brooklyn’s Boerum Hill, Mahoney flanked the living room fireplace with massive custom beech-wood bookcases that completely recast the space’s 19th-century architecture and ornate herringbone oak floor in a more modern light. The vertical partitions of the shelves are wedge shaped — narrower on the face and thicker at the back — to echo a detail of the kitchen cabinets, which are distantly visible across the dining room on the parlor floor.

Mahoney took inspiration for the fronts of the kitchen cabinetry from a book, given to him by the client, whose previous owner had cut words out of the text. He designed the cabinets in the same subtractive manner, carving shallow wedges into the beech surface to create integrated catch pulls for doors and drawers. The effect looks almost Czech Cubist, but the truth is that it has nothing to do with that style and everything to do with its literary origins and organic function.

The furnishings Mahoney selected also serve to update the townhouse’s aesthetic. In the dining room, for instance, a blonde wood Børge Mogensen breakfront cabinet keeps company with a BDDW table, molded plastic Herman Miller chairs and a group of ceramic pendant lights by Natalie Page. The designer contemporized other spaces using items that embody a more modern idea of comfort, like the plushly upholstered BDDW sofa and pair of sheepskin-covered chairs in the living room.

Highsmith was the project director for a commission the designers call Twin Bridges — a historic Eastlake Victorian house in the Upstate New York town of Copake whose original structure Workstead sensitively renovated and then added a modern annex. In the main space of the addition, cherry millwork is built into two sides of an enormous central hearth. One side accommodates shelving for tableware in the dining room before wrapping around to become cabinetry in the kitchen.

As in the other projects, Highsmith complemented the integrated, neat yet warm interior architecture with mid-century and contemporary furniture that ramps up visual tactility through natural materials.

The breakfast area showcases a Nathan Lindberg table surrounded by Gino Russo chairs under Workstead’s Tower pendant. A reproduction of Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy hangs against Eastlake clapboard original to the house.

Around the corner, Highsmith appointed the living area with de Sede sofas and a Nathan Lindberg coffee table, crowning the seating arrangement with the firm’s own Orbit chandelier.

The historical part of the renovation continues the mix of classic modern and contemporary furniture with more period pieces, but in rooms that are more richly colored, in shades reminiscent of Arts and Crafts interiors.

This subtly nudges the Eastlake style just a bit closer to modernity. In the front rooms, painted a saturated blue green from Farrow & Ball, a seating arrangement brings together a contemporary sofa and chunky Clara Porset chairs atop a vintage Laristan rug. On the wall above them is a romantic 19th-century landscape tapestry.

Through their seamless integration of custom-built elements within existing architecture, these projects illustrate Workstead’s process of designing by making. And this process, according to Brechbuehler, frees the trio from adherence to particular aesthetic principles. It is arguably what has made them adaptable to any number of project types.

Among these are renovations of historic properties in styles from Gothic Revival to shingle style and the design of newly constructed freestanding residences and modern multifamily housing (the 64-unit One Prospect Park West and 76-unit Olympia Dumbo, both in Brooklyn). The firm has carved exposed-brick lofts out of industrial buildings and conjured boutique hotels (Dewberry Hotel, in Charleston, and the forthcoming Canoe Place Inn & Cottages, in Long Island’s Hampton Bays) plus restaurants (two underway in Rockefeller Center).

The partners’ role as makers in addition to designers is also one of the qualities that landed them on Architectural Digest’s AD100, the magazine’s annual compendium of the world’s top designers and architects. (They are also darlings of publications as diverse as the New York Times’ T Magazine, Wallpaper and Dwell.)

Their passion for the intelligence of making also accounts for their respectful collaborations with artisans. “It’s about a dialogue,” says Brechbeuhler. “We don’t come in waving a design sword and saying, ‘Make this.’ They are the experts.”

It might be hard for the uninitiated to connect the aesthetic of the firm’s restoration of Twin Bridges with some of their more resolutely modern commissions. But that is because each project is singularly conceived for the specific personality and lifestyle of its owner, and each is constrained by its own unique architecture and history.

Highsmith probably expresses their approach best in the book when he says, “Today, a lot of the time that I spend designing residential spaces is devoted to creating a sense of specificity and place. . . . We align with our clients’ goals, of course. But we also recognize that they are investing their resources toward creating something that has a clear impact on the way they live.”