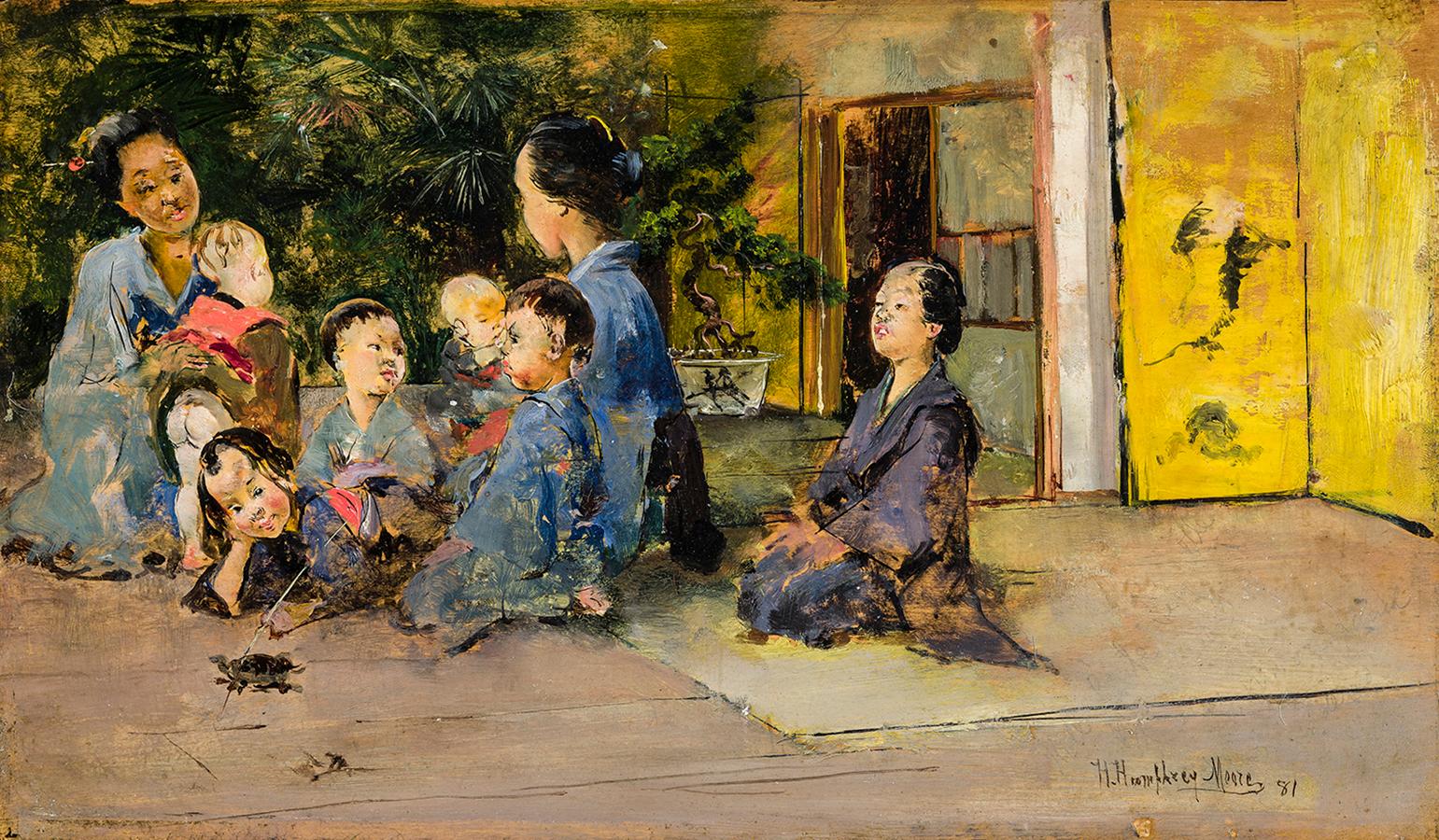

Harry Humphrey Moore led a cosmopolitan lifestyle, dividing his time between Europe, New York City, and California. This globe-trotting painter was also active in Morocco, and most importantly, he was among the first generation of American artists to live and work in Japan, where he depicted temples, tombs, gardens, merchants, children, and Geisha girls. Praised by fellow painters such as Thomas Eakins, John Singer Sargent, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, Moore’s fame was attributed to his exotic subject matter, as well as to the “brilliant coloring, delicate brush work [sic] and the always present depth of feeling” that characterized his work (Eugene A. Hajdel, Harry H. Moore, American 19th Century: Collection of Information on Harry Humphrey Moore, 19th Century Artist, Based on His Scrap Book and Other Data [Jersey City, New Jersey: privately published, 1950], p. 8).

Born in New York City, Moore was the son of Captain George Humphrey, an affluent shipbuilder, and a descendant of the English painter, Ozias Humphrey (1742–1810). He became deaf at age three, and later went to special schools where he learned lip-reading and sign language. After developing an interest in art as a young boy, Moore studied painting with the portraitist Samuel Waugh in Philadelphia, where he met and became friendly with Eakins. He also received instruction from the painter Louis Bail in New Haven, Connecticut. In 1864, Moore attended classes at the Mark Hopkins Institute in San Francisco, and until 1907, he would visit the “City by the Bay” regularly.

In 1865, Moore went to Europe, spending time in Munich before traveling to Paris, where, in October 1866, he resumed his formal training in Gérôme’s atelier, drawing inspiration from his teacher’s emphasis on authentic detail and his taste for picturesque genre subjects. There, Moore worked alongside Eakins, who had mastered sign language in order to communicate with his friend. In March 1867, Moore enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, honing his drawing skills under the tutelage of Adolphe Yvon, among other leading French painters.

In December 1869, Moore traveled around Spain with Eakins and the Philadelphia engraver, William Sartain. In 1870, he went to Madrid, where he met the Spanish painters Mariano Fortuny and Martin Rico y Ortega. When Eakins and Sartain returned to Paris, Moore remained in Spain, painting depictions of Moorish life in cities such as Segovia and Granada and fraternizing with upper-crust society. In 1872, he married Isabella de Cistue, the well-connected daughter of Colonel Cistue of Saragossa, who was related to the Queen of Spain. For the next two-and-a-half years, the couple lived in Morocco, where Moore painted portraits, interiors, and streetscapes, often accompanied by an armed guard (courtesy of the Grand Sharif) when painting outdoors. (For this aspect of Moore’s oeuvre, see Gerald M. Ackerman, American Orientalists [Courbevoie, France: ACR Édition, 1994], pp. 135–39.) In 1873, he went to Rome, spending two years studying with Fortuny, whose lively technique, bright palette, and penchant for small-format genre scenes made a lasting impression on him. By this point in his career, Moore had emerged as a “rapid workman” who could “finish a picture of given size and containing a given subject quicker than most painters whose style is more simple and less exacting” (New York Times, as quoted in Hajdel, p. 23).

In 1874, Moore settled in New York City, maintaining a studio on East 14th Street, where he would remain until 1880. During these years, he participated intermittently in the annuals of the National Academy of Design in New York and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, exhibiting Moorish subjects and views of Spain. A well-known figure in Bay Area art circles, Moore had a one-man show at the Snow & May Gallery in San Francisco in 1877, and a solo exhibition at the Bohemian Club, also in San Francisco, in 1880. Indeed, Moore fraternized with many members of the city’s cultural elite, including Katherine Birdsall Johnson (1834–1893), a philanthropist and art collector who owned The Captive (current location unknown), one of his Orientalist subjects. (Johnson’s ownership of The Captive was reported in L. K., “A Popular Paris Artist,” New York Times, July 23, 1893.) According to one contemporary account, Johnson invited Moore and his wife to accompany her on a trip to Japan in 1880 and they readily accepted. (For Johnson’s connection to Moore’s visit to Japan, see Emma Willard and Her Pupils; or, Fifty Years of Troy Female Seminary [New York: Mrs. Russell Sage, 1898]. Johnson’s bond with the Moores was obviously strong, evidenced by the fact that she left them $25,000.00 in her will, which was published in the San Francisco Call on December 10, 1893.) That Moore would be receptive to making the arduous voyage across the Pacific is understandable in view of his penchant for foreign motifs. Having opened its doors to trade with the West in 1854, and in the wake of Japan’s presence at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, American artists were becoming increasingly fascinated by what one commentator referred to as that “ideal dreamland of the poet” (L. K., “A Popular Paris Artist”).

Moore, who was in Japan during 1880–81, became one of the first American artists to travel to the “land of the rising sun,” preceded only by the illustrator, William Heime, who went there in 1851 in conjunction with the Japanese expedition of Commodore Matthew C. Perry; Edward Kern, a topographical artist and explorer who mapped the Japanese coast in 1855; and the Boston landscapist, Winckleworth Allan Gay, a resident of Japan from 1877 to 1880. More specifically, as William H. Gerdts has pointed out, Moore was the “first American painter to seriously address the appearance and mores of the Japanese people” (William H. Gerdts, American Artists in Japan, 1859–1925, exhib. cat. [New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 1996], p. 5).

During his sojourn in Japan, Moore spent time in Tokyo, Yokohama, Kyoto, Nikko, and Osaka, carefully observing the local citizenry, their manners and mode of dress, and the country’s distinctive architecture. Working on easily portable panels, he created about sixty scenes of daily life, among them this sparkling portrayal of a young woman dressed in a traditional kimono and carrying a baby on her back, a paper parasol protecting them from the summer sunshine. That Moore chose to record this subject is not surprising, for, as one American visitor observed, in Japan “you hardly see a woman without a baby tied on her back . . . fastened . . . by a long strip of cloth wound several times around them and then brought around the waist of the person carrying the child and tied in front. These babies are dressed in kimonos, just like their elders . . . They are odd little bundles of humanity . . . and quite captivating” (Celeste J. Miller, The Newest Way Round the World [New York: Calkins and Co., 1908), p. 258–59). The writer went on, stating that “All babies have their heads shaved,” as is the case with the infant portrayed in this delightful vignette (Miller, p. 259). Moore’s scenes of daily life in Japan have been described as being characterized by “strong and vivid color,” and Japanese Girl Promenading is no exception, the rich palette, as well as the spirited brushwork, revealing the impact of Fortuny (“Oils by Humphrey Moore,” American Art News 18 [January 10, 1920], p. 3). At the same time, the lingering influence of Gérôme is apparent in the artist’s careful portrayal of the sitters’ faces, clothing, and accessories.

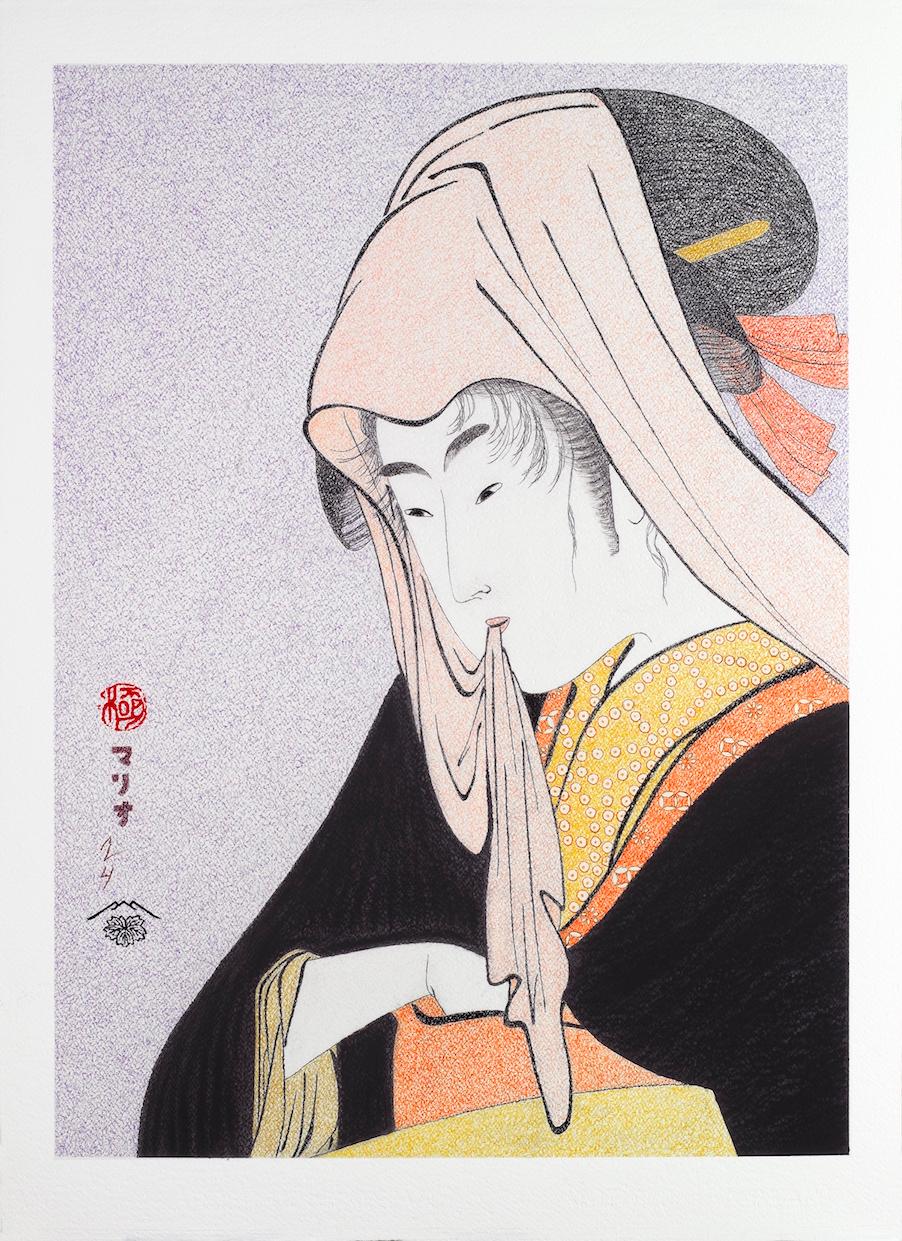

Moore’s involvement with Japanese imagery emerged at a time when japonisme––a term first used in France in 1872 in reference to the impact of Japanese art, culture, and fashion on Western art–– was becoming increasingly fashionable in European and American art circles. Robert Blum, Theodore Wores, and John La Farge were among the American artists who followed in Moore’s footsteps by traveling and painting in Japan. During the late-nineteenth century, other American painters investigated Japanese themes too, but the majority did so within the confines of their studios, working from photographs or using imported artifacts and Caucasian models––which made Moore’s panel paintings, done in situ, all the more exceptional. In fact, treasuring them as souvenirs of his visit and realizing that they represented a way of life that was slowly disappearing, he refused to sell the series to the influential Paris art dealer, Goupil & Cie. Moore is also said to have turned down an offer of $1,000,000 from the financier, J. P. Morgan, although he ultimately agreed to relinquish three of his Japanese panels, selling one to the London art dealer, Sir William Agnew, and two to the prominent American expatriate art collector, William H. Stewart (Hajdel, p. 19). Moore kept the remainder for himself, installing them in his Paris studio in a “curious private collection that was covered at all times with a drape. Only intimate friends had the privilege of seeing this collection for which many people offered alluring sums” (Hajdel, p. 9. For a photograph of the installation, see Hajdel, plate III ).

Later in his career, Moore spent most of his time painting portraits of children and members of the European aristocracy, as well as likenesses of wealthy Americans, including the mother of William Randolph Hearst. He continued to reside in the United States until shortly after World War I, exhibiting his scenes of Japan at the Union League Club (1919) and the Architectural League of New York (1920), at which time they were praised for their “jewel-like quality of color” and “freedom and freshness of spontaneous workmanship” (as quoted in Hajdel, p. 17). A writer for the New York Sun described the works as “tiny affairs . . . packed with curious and attractive details . . . It was a beautiful Japan that Mr. Moore discovered, and now many of the structures and much of the life that he recorded have changed, and not for the better, the artists say” (“Union League Club Begins Art Views,” Sun [New York], November 14, 1919).

After his death in Paris on January 2, 1926, Moore’s Japanese paintings remained with his second wife, the Polish countess Maria Moore, who later hid them from the Gestapo with the aid of a faithful servant. In 1948, the paintings were brought to the United States and exhibited in New York City in September of the following year. In the wake of that show, Eugene A. Hajdel (whose connection to Moore has yet to be determined) issued a thirty-three page booklet that provided details pertaining to the collection, as well as biographical information and a compendium of critical reviews on Moore––the only monographic treatment on the artist to date. Shortly thereafter, according to Gerald M. Ackerman, a prominent scholar of nineteenth-century French art, “Mrs. Moore and the whole collection simply disappeared” (Ackerman, p. 138). He also observed that although Moore’s Japanese subjects and his orientalist pieces have appeared on the art market now and again, for the most part, “they are rare” (Ackerman, p. 138).