April 12, 2020Eileen Gray, seen here in a 1926 portrait by Berenice Abbott, is known for her tubular steel furniture, but she was also an architect at a time when the field was even more male-dominated than it is today (photo courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland, Dublin, © 2019 Estate of Berenice Abbott). Top: Gray’s drawing for Boudoir de Monte Carlo, the room she designed for the 1923 Salon des Artistes Décorateurs (image courtesy of ©MAD, Paris / Christophe Dellière).

In 1973, Andrew Hodgkinson, a London-based interior designer, interviewed the great Eileen Gray in her apartment on the rue Bonaparte in Paris. When Hodgkinson mentioned that Gray’s furniture was beginning to interest collectors, Gray, then in her mid-90s, responded, “The wheel turns so fast now. I might have a sort of a phase of being spoken about. But I’m sure in about a month nobody will ever think of it.”

In the decades since Gray made that prediction, interest in her work has grown exponentially. In 2009, her Dragons armchair, created between 1917 and 1919 for a Paris apartment and later owned by Yves Saint-Laurent, was sold at auction for $28.3 million, setting a record for a piece of 20th-century decorative art.

The high price would have puzzled Gray, and maybe even disappointed her. The chair came very early in her career. With its serpent-shaped lacquered-wood arms, it is pure Art Deco — a style she later disowned as frivolous, both for its focus on ornament and for its use of rare materials. Not only that, the design was figurative, in later years anathema to Gray, who explained to Hodgkinson, “When you see figures, well there it is, you see it, then it’s done. An abstract,” by contrast, “can look so entirely different” each time.

Exhibition view of an incised-wood screen with brown and tan lacquer, 1921–23, and a lacquered wood table à thé (tea table) made before 1926. Photo by Bruce White

The recorded interview is part of a film playing at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery, in Manhattan, where an extraordinary survey of Gray’s career runs through July 12, although it is temporarily closed to the public because of the coronavirus. Hearing Gray speak — in Irish- and French-accented English — is one of the thrills of the exhibition. It is based on a 2013 show at the Pompidou Centre, but with a significant number of additions. Indeed, the tape was not discovered until after the Paris iteration.

Left: Gray’s Fauteuil aux dragons, or Dragons armchair, created between 1917 and 1919 and once owned by Yves Saint-Laurent, was sold at auction for $28.3 million in 2009 (photo courtesy of Christie’s). Right: Table pour petit déjeuner (breakfast table), 1927 (photo courtesy of © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-CCI, Dist. RMN-GP: Jean-Claude Planchet).

Gray is best known for her ingenious tubular-steel furniture, of which there are dozens of pieces in the show. If it has a thesis, however, it is that Gray wasn’t merely a designer — she was also an architect. It may seem superfluous to point this out, but Gray lived at a time when — much more than today — women were “relegated” to design, while the serious work of architecture was reserved for men. That made it easy to overlook her accomplishments in the latter field; so did the loss of almost all Gray’s files over the years. Although she completed only a few buildings, the exhibition includes 12 of her architectural projects and the catalogue an astonishing 44.

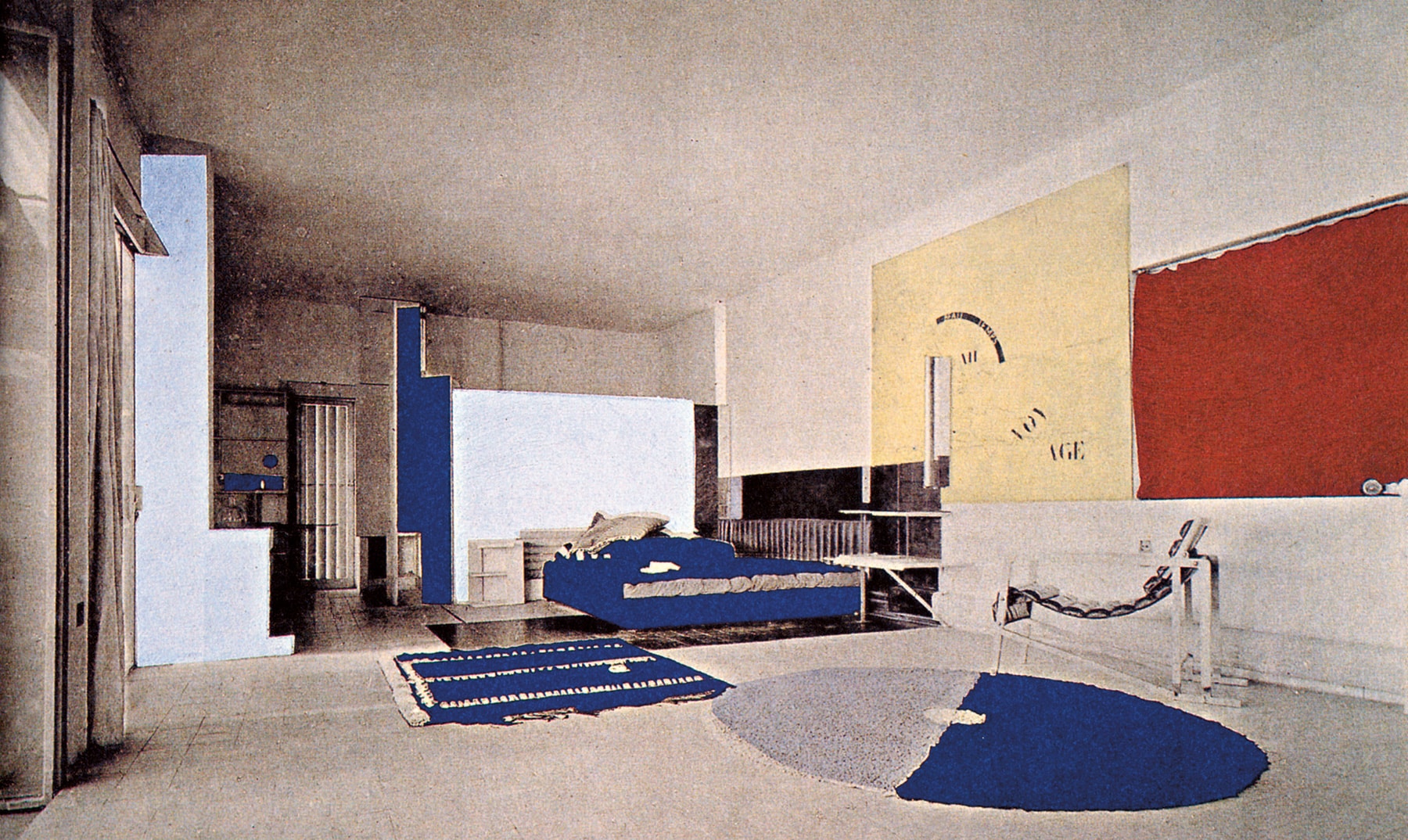

Boudoir de Monte Carlo, shown at the 14th Salon des Artistes Décorateurs, from Intérieurs Français, 1923, an interiors book by Jean Badovici. Photo courtesy of the Archives Galerie Gilles Peyroulet, Paris

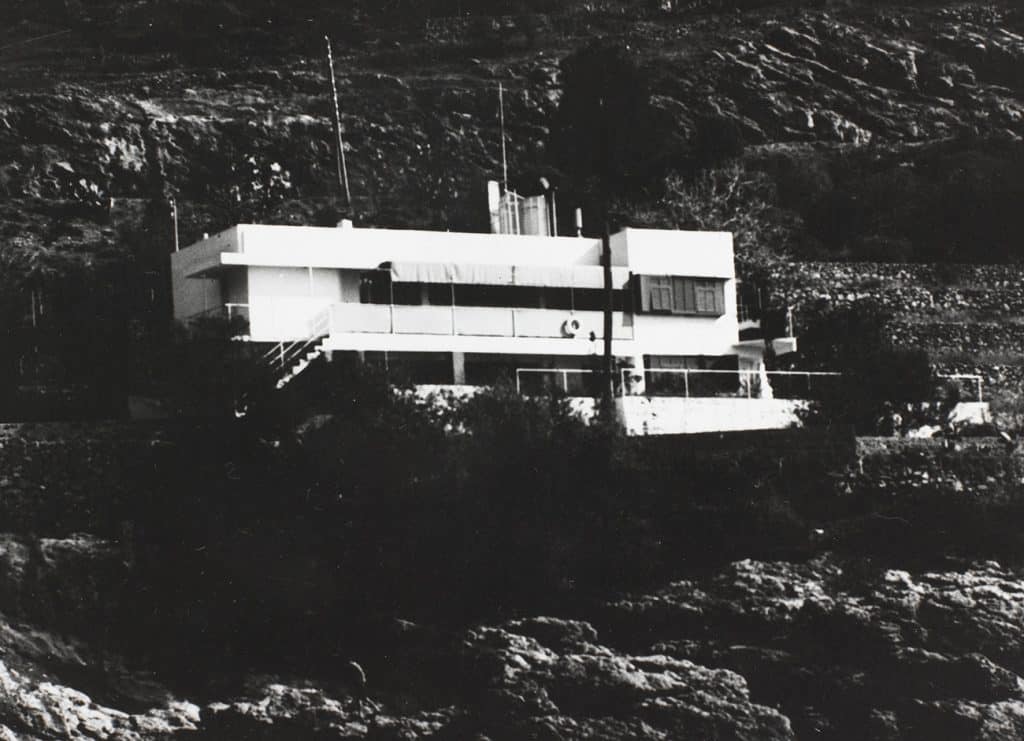

The most famous of Gray’s buildings is E1027, a house in the south of France that she designed in the late 1920s with Romanian-born architect Jean Badovici, her lover at the time. Heavily influenced by Le Corbusier, the narrow house has white stucco walls and metal strip windows and is raised on narrow columns, often called pilotis. Because Badovici was a trained architect and Gray was not, the house was sometimes attributed solely to him. It didn’t help that when Gray and the much younger Badovici split up, she “put the thing in his name because he said he wanted a refuge,” as she told Hodgkinson. Writing in the Bard catalogue, curator Cloé Pitot notes that this was part of a pattern: “Gray always managed to either relinquish authorship or move on from conflicts without looking back.”

Indeed, it wasn’t, by most accounts, until 1968 that the design for E1027 was attributed to Gray, in an article by Joseph Rykwert, a noted architectural historian at the University of Pennsylvania. Pointing out that the E in the name of the house stands for Eileen, Pitot calls Gray “arguably the lead architect on a project that is without a doubt a masterpiece of modern architecture.”

Gray designed her best-known building, E1027, in the 1920s with architect Jean Badovici, her lover at the time. The house, located in the south of France, was for years attributed solely to Badovici. Photo courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Fond Eileen Gray

Yet Pitot writes, “The fact is that there is no concrete evidence to determine which of them did what at E1027.” And, as she told Introspective at the time of the Pompidou show, “No one knows whether Badovici did the architecture.”

An interior of E1027, from L’Architecture Vivante, no. 26 (Winter 1929), a quarterly French architecture publication. Photo courtesy of the Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Fonds Eileen Gray

Worse, the house was sometimes associated with Le Corbusier, a frenemy who took an unnatural interest in the building. In 1938 and ’39, while a guest of Badovici, Le Corbuiser modified E1027 by painting seven murals on its previously white walls, a bizarre act of vandalism with psychological overtones. “Seemingly affronted that a woman could create such a fine work of modernism,” the British architecture critic Rowan Moore wrote in a Guardian article about the house, “Le Corbusier asserted his dominion, like a urinating dog, over the territory.” (He later built his own vacation cabin just a few feet away.)

In this 1930 photo by Thérèse Bonney, Mme Juliette Mathieu-Levy poses in her Paris living room, which was designed by Gray. Photo courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. BHVP/Roger-Viollet RV-39756-7

But if the show focuses on Gray as an architect, it doesn’t slight her work as a designer, which began when she moved from her birthplace in County Wexford, Ireland, to London in 1900. Two years later, she relocated to Paris, where she lived until she died, in 1976. There, she collaborated with the Japanese lacquer master Seizo Sugawara and the Scottish weaver Evelyn Wyld. Examples of her work in both mediums are highlights of the exhibition, given how little-known they are compared with her later furniture. She opened a gallery in 1922 to show her rugs, their patterns reminiscent of Russian constructivism, but didn’t sell many. She told Hodgkinson, “French people are very slow to like anything modern.”

And by the mid-1920s, modernism was everything to Gray. Whereas once she had carved wood and painstakingly applied lacquer and other finishes, now she was creating furniture with sleek lines and surface patterns influenced by the De Stijl movement (the subject of an important show in Paris in 1923). Later furniture capitalized on industrial techniques. The exhibition contains 11 pieces she designed for E1027, including a round, adjustable-height table that is perhaps her most famous design and the hammock-like Transat chair, which, Pitot writes, “allows its user to savor repose and contemplation in suspended time.”

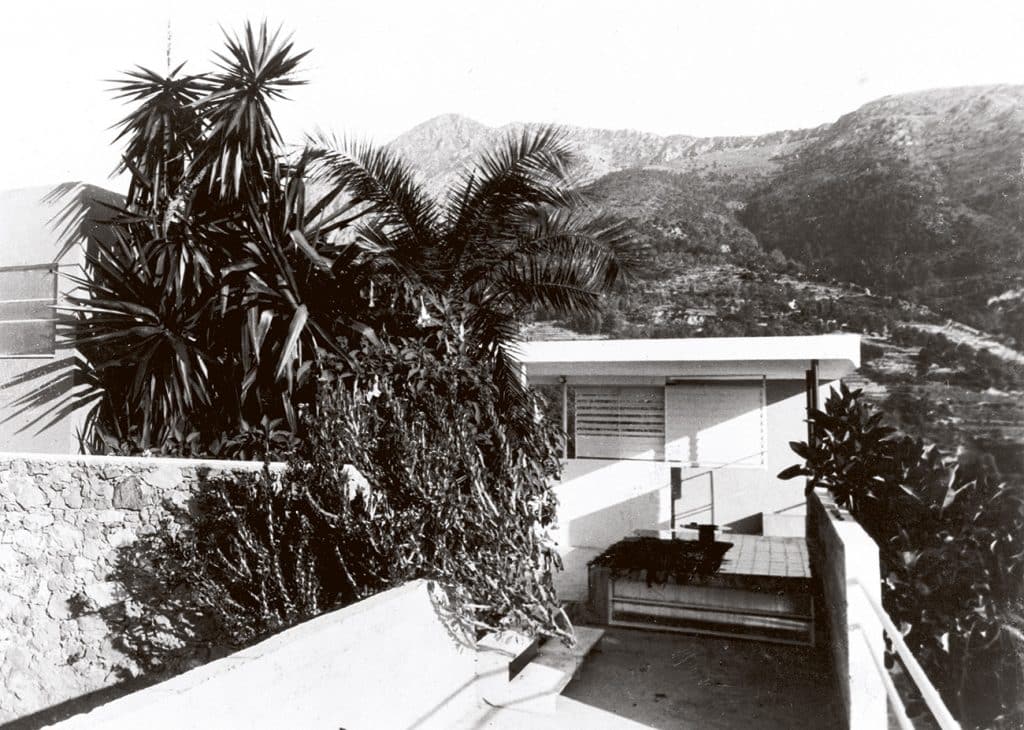

The terrace at Tempe à Pailla, the home Gray built for herself in the south of France after E1027. Photo courtesy of Centre Pompidou, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Paris. Fond Eileen Gray

After she gave the house to Badovici, she built a second retreat for herself nearby, the Tempe à Pailla. But she soon sold that house (to artist Graham Sutherland). As she once told a journalist, “I love doing things. I hate possessing them.” Her third completed building was also her own house, this one in Saint-Tropez.

This bedroom in designer Sara Story’s Texas home, SK Ranch, features Gray’s Transat chair. Photo by Robert Relic

The curators and authors have succeeded in making clear that Gray was more than “just” a furniture designer, yet they have wisely avoided the phrase “woman architect.” Which is a good thing. The catalogue (designed by the Dutch master Irma Boom) makes clear that Gray disliked that label. In 1975, Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, a California artist, organized the first exhibition in the United States dedicated solely to Gray. But the show was at the Woman’s Building, a feminist space in downtown Los Angeles. De Bretteville received a letter from Gray in which she expressed her distaste for the women’s movement and questioned the Woman’s Building designation. “Is this building not for everyone?” Gray wrote. “Surely criticism must only be based on merit,” which, she explained, meant “not emphasizing the difference between individuals.”